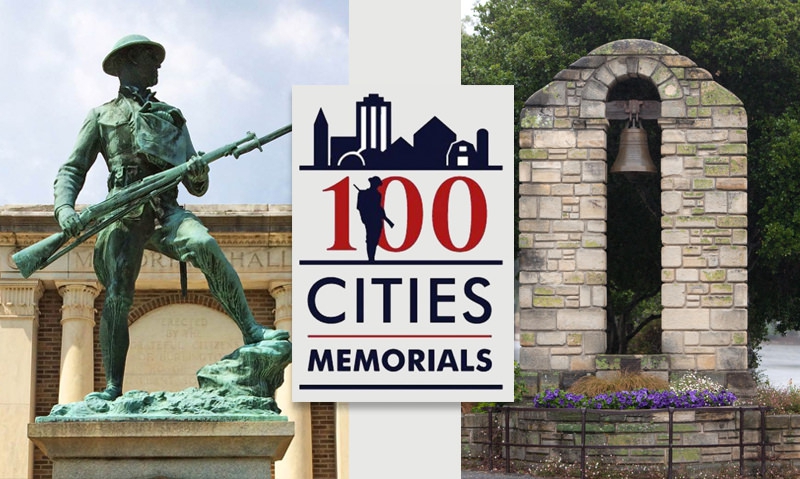

Posts welcome 100 Cities/100 Memorials grants

The World War I memorial in Carmel-by-the-Sea, Calif., is one of the city’s most recognizable and photographed sites.

A Spanish arch made of sandstone, it is nearly a century old and honors 54 local men who served in the Great War. Members of The American Legion laid its cornerstone and, along with the local newspaper, raised money for its construction.

“A thousand dollars in 1921 was a lot of damn money,” says Paul Rodriguez, past commander and general manager of American Legion Post 512 in Carmel-by-the-Sea. “They took donations of 5 cents, 10 cents, 25 cents. They did vaudeville acts, music events, special dinners – all kinds of fundraisers to get the memorial built.”

Like most of the nation’s aging World War I memorials, though, the Carmel arch needs some maintenance. The sandstone is flaking in places and up to 16 stones need replaced. Last year, Legionnaires raised $15,000 from the community to commission a new bell for the memorial, but thousands more are needed for mason work.

Their efforts will get a boost from a matching grant of $2,000 from the 100 Cities/100 Memorials program, sponsored by the Pritzker Military Museum & Library and the U.S. World War I Centennial Commission. On Sept. 27, the first 50 recipients were announced and officially designated “centennial memorials,” with the Carmel-by-the-Sea arch among them.

“To me it was a wish and a prayer,” Rodriguez says. “We’re grateful we’ve been given this opportunity. What an awesome opportunity to complete a project our forefathers started 100 years ago.”

‘Part of the fabric of the community’

The 100 Cities/100 Memorials challenge was created to draw attention to World War I memorials across the country, and to give all of America a chance to get involved with the centennial commemoration by participating in their restoration. The program is supported by The American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars.

The first 50 recipients are in 28 states, with another 50 to be named April 6. Applications for the second round of grants can be submitted here.

The Gold Star Memorial at Guthrie Park in Riverside, Ill., is another awardee. When Joe Topinka took over as commander of Riverside American Legion Post 488, one of the members’ top concerns was the deterioration of the village’s memorial to its war dead – boulders with bronze plaques bearing names of the fallen, World War I through Vietnam, encircling a flagpole.

“We have stones that are sinking, we have plaques that are discolored, we have overgrowth, we have unstable surfaces,” Topinka says. “The World War I part of it especially has kind of succumbed to time and the elements.”

For years, Tom Sisulak – son of a World War II veteran and Sons of The American Legion member – has pushed for the memorial to become a village project. With his help, Topinka applied for a 100 Cities/100 Memorials grant.

“There are people in Riverside who don’t even realize there’s a memorial in the park,” he says. “We started an account a couple of years ago to collect money, and the post donated $5,000. This matching grant will most likely bring us publicity and maybe energize others to donate. The intention has always been a collaboration between the community and the post.”

Topinka hopes buzz about the grant will help revitalize Post 488, too. In a year, his roster has jumped from four or five active members to about 30.

“I’d like to build on that,” he says. “The memorial has become our cornerstone: a cornerstone for the community, a cornerstone for our veterans and a cornerstone for me for outreach.

“I think the most important thing here is for us to come together and talk about what this memorial really represents. That’s worth more than any grant.”

In Pierson, Iowa, news of a grant to help restore the city’s World War I memorial has spread quickly.

“Everybody’s pretty excited about it,” says Chris Weinreich, adjutant of Harrison F. Pedersen American Legion Post 291. “It’s been a fixture here for almost 100 years, and when you study the history behind it you see it’s really part of the fabric of the community.”

One of Pierson’s earliest pioneers, Jens Pedersen, immigrated from Denmark. Two of his three sons fought in Europe: David (“Davey”) made it back, while Harrison (“Harry”) was killed near Chateau Thierry on July 18, 1918. His name, along with two others, is etched on the Pierson monument – a 12-foot granite obelisk capped with a globe and a brass eagle representing a triumphant America.

“Three men from three different families,” Weinreich says. “This was too close for comfort, and the town had a difficult time reconciling the loss. So they set about to honor their sacrifice in the best way they knew.”

Between November 1918 and the end of 1920, the people of Pierson raised nearly $4,000 to erect a memorial on Main Street Boulevard. It’s a source of pride for the city, but Post 291 intends to clean the monument and improve the surrounding area.

“The concrete work around it has fallen into disrepair,” Weinreich says. “What we’re looking to do is replace the curbing and steps, and we want to introduce some new lighting that will highlight the monument and the flagpole behind it.”

He learned of the 100 Cities/100 Memorials program through the Legion’s national website, and the post’s members voted to apply for a matching grant. The $2,000 puts them closer to their goal; Weinreich estimates repairs could cost up to $15,000. In addition, he plans to solicit donations from businesses and people in the community.

With the help of the Legion Family and city leaders, “we will get it done,” he says.

‘People who stood up for their country’

On May 30, 1925, a crowd of 2,000 attended the dedication of the World War I doughboy monument at Cape Girardeau County Courthouse in Jackson, Mo. Made of Vermont white marble, with a height of 16 feet, the soldier is a tribute to all who served in the Great War. Attached is a bronze plaque with the names of 40 local men and women who served, of whom 16 died on the battlefield.

Time and weather have taken a toll on the marble, but a full restoration is underway, thanks to a memorial fund created by Altenthal-Joerns Post 158 in Jackson. A cleaning of the plaque is complete, and there are plans for an ADA-compliant sidewalk and rose garden at the base of the monument.

Major donations have come from corporate sponsors like Liberty Utilities and the Jackson and Cape Girardeau branches of The Bank of Missouri, as well as the Retired National Guard Association of Southeast Missouri. A World War I rifle raffle and a 100 Cities/100 Memorials matching grant will help pay for the project, too.

“I think we’re going to have the funds we need,” says Lawson Burgfeld, a past commander of Post 158. “Whatever money is left over will be put into a fund for preservation from this day forward.”

Burgfeld grew up in Cape Girardeau County and has researched each person named on the memorial’s plaque – including Clarence Altenthal and Clark Joerns, the first two Jackson men killed in action and the namesakes of Post 158. The first Cape Girardeau soldier killed in action was Lt. Louis K. Juden; American Legion Post 63 in Cape Girardeau is named in his honor.

In addition, the plaque names two women and four African-American soldiers.

“That’s a tribute to the citizens of southeast Missouri and Cape Girardeau County, that 100 years ago they included each and every individual who justly deserved to be on there,” Burgfeld says.

He recently discovered six more names that should be added to the memorial, and hopes to have short biographies for the entire group in time for the doughboy’s rededication on Memorial Day.

“These are people who need to be thanked,” Burgfeld says. “Granted they are long gone, but they need to be remembered as people who stood up for their country and did what was right.”

Like Burgfeld, Frank Caruso of Burlington, N.J., has spent years researching his city’s World War I memorial, dubbed the “Rock of the Marne.”

In the early 1920s, citizens donated money to build a memorial hall complex, which included a statue out front of a U.S. soldier in combat gear, bayonet at the ready and gas mask slung from his neck. It’s a replica of a famous monument in Syracuse, but the choice is a mystery. Did the 38th Infantry Regiment, called the “Rock of the Marne” for its fierce fighting in the Second Battle of the Marne, have ties to Burlington? Or is the statue simply what the foundry sent?

“This is a good opportunity to dig into the back story of how the monument got here and why,” says Caruso, commander of Sons of The American Legion Squadron 79 in Burlington. “Ultimately it’s a piece of public art, done by a renowned sculptor. You want to keep these pieces from falling into disrepair to the point where they have to be removed.”

Years ago, he noticed streaking on the monument and wondered when, if ever, it had been cleaned. His father and brother are members of Capt. James MacFarland American Legion Post 79, and when Caruso became involved in the SAL, he made it a goal to get some attention for the Rock of the Marne “so we don’t lose it to corrosion and time,” he says.

When he heard about the 100 Cities/100 Memorials program, Burlington’s Legion Family had about $3,000 in money raised through personal donations and a charity softball game put on by the city. A matching grant, corporate donations and more grassroots fundraising will make it possible to have the monument inspected for structural damage, cleaned and waxed.

“I’m pretty confident we can hit the mark in the next six months,” Caruso says.

He’s eager to see the Rock of the Marne gleaming again, so that the citizens of Burlington will reflect on World War I and what it meant for their city.

“This project has opened my eyes to the fact that a lot of people don’t even realize the monument is there,” he says. “They drive by it, they walk by it, day after day after day. It’s important for citizens to be reminded of the sacrifices made. We have a school directly behind the building, and for those kids to see the monument and understand what it means ... there’s an educational component to it.”