OUR WWII STORY: GI Bill educates new era of veteran farmers

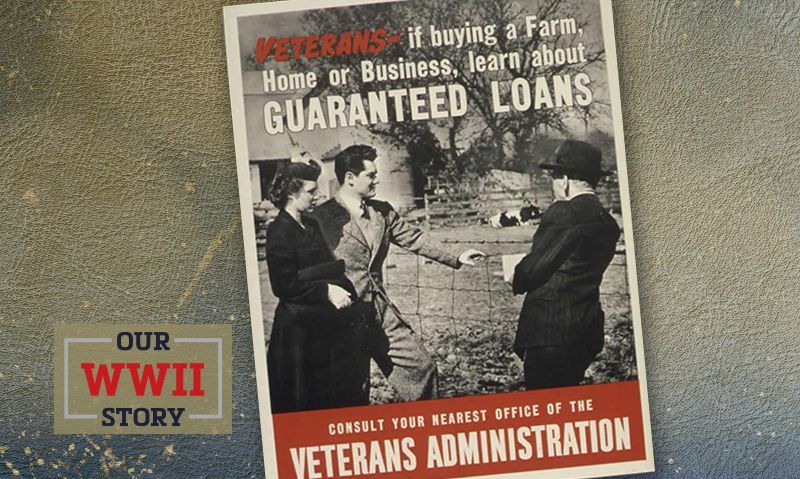

Among the GI Bill’s future-changing economic planks was a focus on low-cost loans and free training in modern agriculture. Federally guaranteed farm and business financing provided capital for hundreds of thousands of veterans looking to buy land, stock, equipment and knowledge after World War II.

An American Legion National Committee on Agriculture was formed by resolution in December 1945 to give career-hungry World War II veterans not only an opportunity to effectively raise crops and livestock for a living but also to promote responsible land use through soil conservation, efficient water management and sustainable logging.

“Modern agriculture is a highly technical occupation, requiring scientific and practical training,” the resolution stated. “The necessity for service and advice, development and encouragement of farmer veterans of a specialized and technical nature is now apparent.”

Over the next decade, more than 750,000 World War II veterans partook of the GI Bill’s agricultural education program, and tens of thousands of farms were financed by the GI Bill and other federally backed loan programs specifically for veterans.

In 1950, the committee morphed into the American Legion Agriculture and Conservation Committee, led by Robert C. Morrow of Mississippi. He reported to the 1950 American Legion National Convention in Los Angeles that new approaches to natural resource industries were important not only to the economy but to national security, as well.

“Agriculture plays a vital role in the welfare and defense of our nation,” Morrow reported to the convention. “We have taken, and continue to take, more plant food from the soil than we put back. Soil conservation should be given immediate consideration in all parts of our country and in all types of agriculture.”

As dams continued to be built in the West, and irrigation practices were evolving, water control grew as a national priority. “We have recently seen the largest city in our nation experience a water famine,” Morrow said. “If the water fails in one section of the nation, it affects the whole. If the groups of one section of our country suffer because of droughts, flood or other acts of nature, the impact is felt by the entire nation, and is a problem of national scope.”

Logging without replanting was also viewed as national problem, the Legion committee chairman said. “We have cut timber without restoration, in many instances, leaving behind nothing but stumps on what was once the finest of timber stands. The matter of restoration is one that should be given careful study by the government and by private enterprise.”

The committee recommended a multi-pronged policy where American Legion departments and posts would coordinate with local, state and federal land-use agencies along with private industry to advance the importance of sustainable agriculture and logging.

Morrow made the case that “the problem” went beyond the need to help veterans move forward in their careers. “Many agriculture and conservation problems cannot be solved by separating veterans’ problems from citizenship as a whole,” he said. “This program is vital to America and will be a stimulus in combatting un-American movements in our nation.”

The policy further recommended that the Legion collaborate with agricultural colleges and other groups to organize state roundtable discussions and conferences to advance conservation-minded farming, ranching and logging for the years ahead. The objective, according to Morrow’s report, was “to create a consciousness in the minds of people of the importance and need of developing a permanent, workable, effective program for agriculture and conservation; taking into consideration … soils, land use, water (surface and sub-surface), financing and credit, minerals, health, education, recreation, game and fish (both as food and recreation), availability of markets, transportation, reclamation of lands, forests and streams; to promote national defense, to improve the standard of living and to sustain a rapidly growing population.”

An August 1955 American Legion Magazine article reported that in Mississippi alone, nearly 40,000 veterans had enrolled in the GI Bill-supported American Vocational Association Committee on Institutional On-Farm Training Program. Among the accomplishments, according to the article, was that veterans had been able to purchase more than 10,000 farms, conduct $24 million in construction and repairs and purchase over $30 million in machinery. “These veterans also bought more than 11,000 purebred dairy cattle, 8,300 purebred beef cattle and 18,000 registered hogs,” the article added.

Those developments had a ripple effect on the U.S. economy, the article added. Income from the agricultural operations fueled by the GI Bill brought electricity to some 12,000 farm families, introduced running water for another 9,000 farm homes and built more than 4,000 bathrooms to replace the old outhouses.

Moreover, the GI Bill farm and agricultural education loans and benefits created new expectations for veterans, many of whom grew up poor farm kids during the Great Depression. American Legion National Commander Erle B. Cocke Jr. wrote in 1951 of his encounter in Texas with a World War II veteran who had used the GI Bill for modern farming education benefit.

“Although the farm was located in one of the poorer sections of the state, the land was fertile and prosperous, and the farmhouse was equipped for good living,” Cocke explained. “He said that (the GI Bill program) had raised him from a tenant with a bleak future to the level of an independent farmer with a promising future. ‘The GI Bill training has changed the world for me,’ exclaimed the sun-bronzed ex-Gl. ‘Believe me, mister, if I learned nothing else from my schooling, I learned this: I'm going to see to it that my children also get an education.’”