Exposure Wars: The long, connected and continuing fight for accountability.

Since their first encounter with nuclear weapons tests in the 1940s, U.S. servicemembers have been exposed to atomic radiation, toxic defoliants and choking burn pits, among other contaminations that, while slower-acting, are often just as lethal as bullets and bombs. In each of these situations, the government response to afflicted veterans’ needs for information, acknowledgment and health care has been even slower – decades of denial, followed by begrudging but limited acceptance and bureaucratic skepticism. The American Legion has been at the forefront of advocating on behalf of these veterans, from the Legion service officer in Iowa who helped Orville Kelly win the first atomic veteran’s claim, to the continuing fight for Agent Orange benefits and today’s work on behalf of post-9/11 veterans.

In this second article of a three-part series, The American Legion Magazine examines the long fight to provide health care and benefits for veterans exposed to Agent Orange – a battle that continues for many former servicemembers who are suffering the consequences of the massive toxic herbicide campaign without help from VA.

From the moment Julie Diane Haley was born with a hole in her heart and underdeveloped lungs, her family suspected it was a consequence of her father’s service in Vietnam. But they weren’t aware of Operation Ranch Hand or the millions of gallons of toxic herbicides the U.S. military sprayed in Southeast Asia. So when Alton and Iralee Haley buried their only daughter four months later, they were left only with questions.

Their suspicions grew as Alton’s health problems multiplied: high blood pressure, heart disease, peripheral neuropathy, prostate problems and more. Each new diagnosis brought another frustrating battle for VA health care and benefits.

This is the story for thousands of veterans and their families. On the one hand, more than half a million people are now receiving Agent Orange benefits thanks to the dogged advocacy of The American Legion, the National Veterans Legal Services Program (NVLSP) and other groups. Billions of dollars in claims have been paid as a result of their victory in Nehmer v. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs as well as the Agent Orange Act of 1991. “There’s been a lot of progress,” says Bart Stichman, executive director of NVLSP.

Yet a significant number of veterans are still fighting VA, even those who had “boots on the ground” in Vietnam and should therefore automatically qualify for Agent Orange benefits for more than a dozen diseases presumed caused by exposure to the U.S. military’s arsenal of toxic herbicides. Many give up after the second or third VA denial. Other veterans suffer for decades, without knowing they qualify for help.

Blue Water Navy veterans – who drank and showered in distilled seawater contaminated by Agent Orange-laced runoff from Vietnam – are still trying to regain benefits VA withdrew in the early days of the George W. Bush administration. And former servicemembers who believe they were exposed to toxic herbicides in Thailand, Korea, Guam, Okinawa and military bases in the United States can expect to have their claims denied.

If that’s not grim enough, VA has not added benefits for any diseases that science shows are connected to toxic herbicide exposure since 2015, when Congress allowed provisions of the Agent Orange Act to lapse that required VA to make decisions within 180 days.

“It’s a relentless tragedy,” says Fred Wilcox, author of “Waiting for an Army to Die,” one of the first books to chronicle the carnage wrought by Agent Orange when it was published in 1983. “We pay a lot of lip service to people who serve in the military. But the reality is we expose them to radiation, we expose them to Agent Orange, we expose them to depleted uranium and burn pits, and then go into a fit of denial when they become ill.”

The cost to veterans and their families is staggering, adds William Davis, a Blue Water Navy veteran. “The pain, the suffering is deep. And for the survivors, the grief when the veterans die is both welcoming for the end of the suffering and frightening for what the future holds.”

PERIMETER PATROL A neighbor introduced Alton and Iralee at a teen recreation hall in Texas shortly before he entered the Air Force in 1969. The couple got to know each other through letters they exchanged during Alton’s yearlong deployment to Vietnam. A security dog handler, he knew the U.S. military was spraying something around the perimeter of the air bases in Da Nang and Phan Rang where he patrolled. “I didn’t know what it was,” Alton says. “I didn’t know it was poisonous to people.”

Alton and Iralee married in August 1970, soon after he returned from Vietnam. He finished his hitch at Altus Air Force Base in Oklahoma and became a homebuilder in Texas. In 1980, their daughter was born three months premature, and Alton’s mother was certain his service in Vietnam was the reason. He began experiencing health problems at odds with his family’s history.

“I’d always pondered it,” Iralee says of her mother-in-law’s belief that something in Vietnam was to blame for the loss of their daughter. “When all of this stuff started happening to him, I began to think about it again.” Iralee asked several VA doctors if there was a connection between Alton’s service in Vietnam and his ischemic heart disease. The doctors told her to drop her inquiry. “They said, ‘It’s not going to do you any good because it’s not service-connected.’”

Iralee filed Alton’s first VA claims in the 1990s – and continued to file and appeal over the next several years. “They denied and denied it was service-connected,” Iralee says of Alton’s health problems, many of which are now presumed connected to Agent Orange exposure. VA even denied that Alton had heart disease, even though his own VA doctors had made the diagnosis following an angiogram.

More medical issues appeared: type 2 diabetes, prostate problems, and the sudden onset of peripheral neuropathy so severe that Alton had to learn how to walk again. “There’s an old saying,” says Alton, who had to retire at 55 because of his failing health. “The war killed me, but I’m not dead yet.”

VA kept denying his medical claims. Iralee kept appealing, eventually receiving some benefits. She eventually found NVLSP, and the nonprofit legal advocacy group won retroactive compensation for Alton’s ischemic heart disease as a result of the federal court ruling in Nehmer.

DELAY AND DENY In the years after the war, VA maintained that a painful, blistering skin rash known as chloracne was the only illness caused by Agent Orange exposure. This was the story even as Wilcox and journalists nationwide reported on Vietnam veterans dealing with testicular cancer, bladder cancer, multiple miscarriages, babies with severe and inexplicable birth defects, and other problems.

By the late 1970s, Sen. Alan Cranston, chairman of the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee, told VA that its denial of nearly all Agent Orange claims suggested the federal government was covering up evidence about the hazards of toxic herbicide exposure in much the same way as information about the adverse health effects from radiation was withheld from nuclear-weapons test participants in the 1950s and 1960s, according to Wilcox’s book. Not only were Alton Haley’s illnesses excluded under VA’s chloracne-only rule, but he couldn’t win a simple hearing-loss claim even though he served on the flight line at Altus.

In 1986, NVLSP filed a class-action lawsuit against VA’s chloracne-only rule on behalf of hundreds of thousands of Vietnam veterans and their survivors – Nehmer v. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. A federal court ruled against VA in 1989, ordering the agency to rewrite its Agent Orange regulations and redo claims it denied under its illegal rules.

Next came the Agent Orange Act of 1991, directing VA to revisit scientific research regarding toxic herbicide exposure every two years, then provide Agent Orange benefits for additional diseases on the recommendation of the National Academy of Sciences. That same year, a consent decree in the Nehmer case required VA to provide retroactive compensation for all pertinent claims it had previously denied. NVLSP had to repeatedly return to court to enforce that decree, and is the court-appointed watchdog over any new Nehmer claims.

Many Agent Orange issues remain unresolved, however. Legislation to restore benefits for Blue Water Navy veterans has repeatedly failed to receive a vote in Congress. The latest effort, introduced in the House in May, proposes to pay for benefits by increasing fees veterans and servicemembers pay on VA loans. VA, meanwhile, has denied claims of veterans exposed to Agent Orange at U.S. bases such as Fort Drum, N.Y., though it acknowledges the herbicide was used there.

Barbara Wright’s late husband believed he was exposed to Agent Orange in Korea in 1962 and 1963. However, VA only recognizes claims from servicemembers who can establish they were at the DMZ between April 1968 and August 1971. Joe Dunagan was part of a clandestine Army special ops unit whose records remain classified, so he was never able to prove he’d served overseas, Wright says.

Dunagan died in early March, soon after he was diagnosed with liver and lung cancer. Wright is pushing ahead with her survivor’s claim, including sending repeated records requests to DoD and the CIA. Struggling to get by on $600 a month, she is mystified that the government isn’t forthcoming more than 50 years after Dunagan came home. “If you served in Korea during the Vietnam War and need documentation for a VA claim and it isn’t in your 201 file, you are basically screwed,” Wright says. “When will somebody expose the plight of Korean vets?”

After all these years, there are also Vietnam veterans who are unaware they might be eligible for help. They include John Naldrett, a retired Savannah, Ga., firefighter and Navy veteran who is dealing with prostate and colon cancers. He learned about Agent Orange benefits from a former shipmate just a few years ago and filed a claim, which VA promptly rejected. He’s appealing, a task made more daunting by the fact that he’s in the last eight to 10 years of his life, he says.

There are illnesses that the National Academy of Sciences found sufficient evidence to connect to toxic herbicide exposure in 2016. But VA still has not added bladder cancer, hypothyroidism, high blood pressure or Parkinson’s-like symptoms to the list of Agent Orange presumptions.

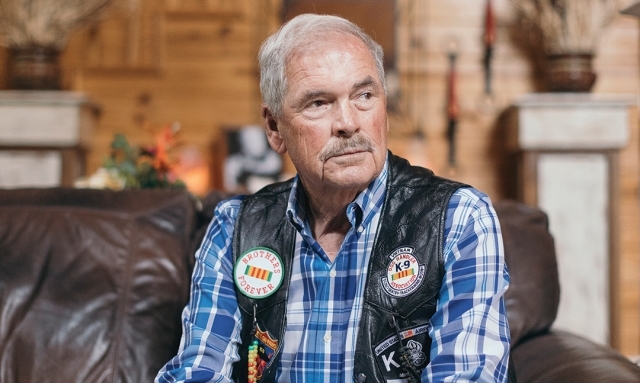

“We’ve been fighting since 1978 and not getting any response,” says Brian Russ, a member of American Legion Post 266 in Sarasota, Fla., who was a helicopter pilot in Vietnam. His bladder cancer claim has been denied four times. “I can understand why so many veterans get depressed and give up,” Russ says. “Congress has to say, ‘Let’s get this done and quit giving veterans the runaround.’”

And for Alton and Iralee, there’s VA’s steadfast denials that Julie Diane Haley’s premature birth and untimely death were caused by Alton’s Agent Orange exposure. “I think their aim is to prove the veteran wrong,” Iralee says. “I’ve finally let it sit – with the hope that maybe someday VA will finally recognize that something happened.”

Ken Olsen is a frequent contributor to The American Legion Magazine.

Agent Orange: A Timeline

World War II The two key components of Agent Orange 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D are tested at Fort Detrick, Md.

June 1959 Military tests aerial spraying of Agent Orange at Fort Drum, N.Y.

1961 Army conducts first field tests of Agent Orange in Vietnam.

1962-1972 U.S. military sprays some 20 million gallons of Agent Orange and other toxic herbicides across Vietnam and some parts of Laos as part of Operation Ranch Hand. While the program included herbicides code named Agents White, Blue, Purple, Pink and Green, Agent Orange was used in the greatest quantity.

1964 U.S. military tests aerial applications of Agent Orange and other chemical defoliants in Thailand.

Dec. 20, 1966 The American Association for the Advancement of Science passed a resolution citing “concerns regarding the long-range use of the use of biological and chemical agents which modify the environment.”

February 1967 A petition signed by more than 5,000 scientists, including 17 Nobel laureates, asks President Lyndon Johnson to end the use of herbicides in Vietnam.

Nov. 25, 1967 Arthur W. Galston, a Yale botany professor, warns that the use of defoliants in Vietnam might harm people living in the areas that were sprayed.

1968-1971 U.S. military uses Agent Orange at Korean DMZ.

Jan. 7, 1968 A Pentagon report concludes the use of Agent Orange and other defoliants in Vietnam won’t have any long-term environmental effects.

April 15, 1970 The White House announces a ban on the use of one of the key components of Agent Orange around homes, schools, food crops and similar uses because of concerns about the consequences of human exposure to the herbicide. The U.S. military also stops using Agent Orange in Vietnam but continues its use of other chemical herbicides.

Dec. 26, 1970 The Nixon administration announces it will phase out herbicide spraying operations in Vietnam.

Feb. 12, 1971 The U.S. military announces is will stop using herbicides to destroy crops in Vietnam and the use of C-123 airplanes to spray defoliants ends. However, chemical herbicides continue to be sprayed by helicopter and ground troops around U.S. fire bases.

Oct. 31, 1971 The U.S. military stops using helicopters to spray herbicides in Vietnam.

Early 1970s Veterans begin complaining of strange skin lesions called chloracne and other health problems as well as a spike in birth defects in their children. VA requires proof of exposure from anyone filing a claim for benefits.

1974 The National Academy of Sciences’ Committee on the Effects of Herbicides in Vietnam reports that dioxin, a component of Agent Orange, “is extremely toxic to some laboratory animals.”

March 23, 1978 WBBM in Chicago airs “Agent Orange, the Deadly Fog” – an Emmy Award-winning documentary that started with a tip from Maude DeVictor, an employee at the Chicago VA’s regional office. DeVictor compiled information from veterans suffering from illnesses they believed were caused by Agent Orange exposure, widows who had lost their husbands to those illnesses, and the families of veterans who were dealing with multiple miscarriages and birth defects.

Nov. 27, 1979 Orville E. Kelly, a 49-year-old member of American Legion Post 52 in Burlington, Iowa, announces that he has been approved for VA disability compensation for lymphatic cancer related to ionizing radiation exposure in 1957 and 1958 during 22 atomic tests he witnessed in the Marshall Islands. He dies seven months after the decision, which VA argues does not set a precedent for veterans seeking disability benefits for other service-related radiation exposure. The decision, however, is cited in efforts to obtain recognition and benefits for others exposed during military service and for those who came into contact with Agent Orange during the Vietnam War and with burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. Following his death, Kelly’s widow, Wanda, assumes leadership of the National Association of Atomic Veterans, which works to gain government acknowledgement and treatment for conditions related to radiation exposure in the military.

1979 A class action lawsuit representing 2.4 million veterans exposed to Agent Orange is filed in federal court against seven large chemical companies who manufactured the deadly herbicide. The case goes all the way to the Supreme Court and results in a $240 million settlement in 1988.

Dec. 20, 1979 Congress orders VA to study the long-term health affects of exposure to dioxin, a component of Agent Orange.

1982 VA decides that Vietnam veterans with chloracne are presumed to have been exposed to Agent Orange.

January 1982 The American Legion Magazine publishes the first of a three-part series titled “Agent Orange: Time Bomb or Dud?”

Feb. 25, 1982 An American Legion medical consultant tells VA officials their “preference for secrecy would increase Vietnam veterans’ distrust of a scientific study designed to determine whether the veterans suffered health damage from exposures to Agent Orange.”

March 12, 1982 Dow Chemical, a major manufacturer of Agent Orange, suggests an exotic Asian bacterium caused a growing number of health problems among Vietnam veterans instead of toxic herbicide exposure, according to the American Legion News Service.

May 3, 1983 Fred Wilcox’s “Waiting for An Army to Die,” one of the first full-length book’s dedicated to the devastating consequences of Agent Orange exposure on Vietnam veterans, is published.

Oct. 24, 1984 The Veterans’ Dioxin and Radiation Exposure Compensation Standards Act is signed by President Ronald Reagan. It requires VA to establish Agent Orange compensation guidelines for veterans exposed to toxic herbicides. The legislation also provided compensation to atomic veterans who became ill as a result of their exposure to decades of above-ground nuclear weapons tests.

1984 Congress orders VA to assemble a scientific committee to draft regulations to provide medical care and benefits to Vietnam veterans who can prove they were exposed to Agent Orange. VA’s committee says only veterans with chloracne should qualify.

The U.S. Army Toxic and Hazardous Materials Agency writes a letter saying Agent Orange was used to kill brush along the roads at Fort Drum, N.Y.

1986 National Veterans Legal Services Program files suit challenging VA’s “chloracne only” rule on behalf of hundreds of thousands of veterans and survivors. It wins the case – Nehmer v. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California and is one of the most far reaching Agent Orange exposure legal victories.

1988 Dr. James Clary, an Air Force researcher involved with Agent Orange use in Southeast Asia, sends a letter to USen. Tom Daschle saying, “When we initiated the herbicide program in the 1960s, we were aware of the potential for damage due to dioxin contamination in the herbicide. However, because the material was to be used on the enemy, none of us were overly concerned. We never considered a scenario in which our own personnel would become contaminated with the herbicide.”

May 15, 1989 The U.S. District Court for Northern California rules that VA was wrong when it arbitrarily decided chloracne was the only disease caused by Agent Orange exposure and orders the agency to reconsider all claims it rejected under that illegal regulation. rules that the VA set evidentiary standards for connecting Agent Orange to diseases too high there by stacking the deck against veterans filing dioxin-related disability claims.

Jan. 15, 1990 VA Secretary Edward Derwinski delays decision on Agent Orange benefits for Vietnam veterans.

March 12, 1990 The American Legion Magazine announces a new publication about Agent Orange that is distributed at the Washington Conference. The reprint includes an excerpt from “Wages of War” by Richard Severo and Lewis Milford, which deals with the way America’s veterans have been treated since the Revolutionary War.

March 26, 1990 The American Legion says it doubts a forthcoming CDC study will do right by Vietnam Veterans exposed to Agent Orange. “Vietnam veterans who were exposed to Agent Orange have been poked, prodded and literally studied to death for the past dozen years,” National Commander Miles S. Epling said. “But the federal government continues to mislead and misdirect attention from this generation of war time veterans. If the nation cannot bring itself to compensate these victims of the Vietnam War, then the nation is guilty of lying to those veterans and every service member who puts on the country’s uniform.”

March 29, 1990 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention finds veterans who served in Vietnam War have a far higher rate of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma than veterans from the same era who didn’t serve in and around Vietnam. The Selected Cancers Study also concludes that highest incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was experienced by military personnel who served on ships off the coast of Vietnam. However, the same study says Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange did not have a higher rate of five other cancers and is one of the reasons’ the study is controversial.

April 23, 1990 The American Legion labels the CDC’s “Selected Cancer Study” of Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange scientific fraud. “The American Legion wants the lying to end today,” National Commander Miles S. Epling said. The study also draws withering criticism from some members of Congress and the Government Accounting Office.

Feb. 6, 1991 President George H.W. Bush signs the Agent Orange Act of 1991, which says any veteran who served in Vietnam from Jan. 9, 1962 to May 7, 1975, is presumed to have been exposed to Agent Orange and automatically qualifies for disability rating and medical care for a list of specified diseases. The legislation also orders VA to revisit scientific research regarding toxic herbicide exposure every two years, then provide Agent Orange benefits for additional diseases on the recommendation of the National Academy of Sciences. That same year, a consent decree in the Nehmer case required that VA provide retroactive compensation for all pertinent veterans’ claims that it had previously denied.

February 2002 Under the direction of the Bush administration, VA changes its rules to require Navy and Marine veterans who served on ships to prove they also had “boots on ground” in Vietnam to qualify for Agent Orange benefits.

Dec. 12, 2002 Alarmed at higher than normal rates of cancer in its sailors who served in Vietnam, the Royal Australian Navy publishes study showing distilling water on Navy ships magnifies the concentration of dioxin – a key toxic ingredient in Agent Orange.

April 17, 2003 A Columbia University team led by Jeanne Manger Stellman publishes an analysis of U.S. military flight records showing that up to four times more Agent Orange and other herbicides were sprayed during the Vietnam War than previously estimated. Stellman’s team also was able to build a maps showing where defoliants were sprayed in relation to U.S. troops on the ground – and as many as 4 million Vietnamese villagers.

2003 The American Legion recognizes chemist Jeanne Mager Stellman and her husband Steven, an epidemiologist, with the Distinguished Service Medal for their decades of work on Agent Orange exposure.

Jan. 30, 2004 Vietnamese citizens file a class action lawsuit against 30 chemical companies over health problems inflicted by Agent Orange. Federal courts dismissed the lawsuit in 2005 and again in 2008.

2004 VA denies an Agent Orange claim for Jonathan Haas, a retired Navy commander who served on an ammunition tender in Vietnam who has Type 2 diabetes and kidney problems. Both illnesses can be caused by Agent Orange exposure.

2006 The Australian government authorizes benefits for their Blue Water Navy veterans from Vietnam War.

2007 The George W. Bush Administration requests introduction of legislation to eliminate all Blue Water veterans from qualifying for presumptive exposure to Agent Orange, reflecting an earlier executive order. Bush’s Agent Orange exclusion legislation is introduced, but dies in Congress.

2008 The Institute of Medicine, an arm of the U.S.’s National Academies of Science confirms the Royal Australian Navy finding that distilling seawater for drinking water increases dioxin concentration. VA responds by saying more study is needed.

May 2008 U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit overturns the 2006 Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims ruling in favor of Hass, saying VA had the right to change its rules for Agent Orange eligibility and exclude Navy and Marine personnel who served on ships off the coast of Vietnam but cannot prove they set foot on land in Vietnam.

October-November 2008 The National Veterans Legal Services Program appeals the Circuit Court decision in the Hass case to the Supreme Court. The American Legion and other groups file briefs in support of Hass’ case.

January 2009 The Supreme Court refuses to hear the Hass case, effectively upholding VA’s right to exclude Blue Water veterans. VA rejects pending claims of Blue Water Veterans without proof of boots on ground.

May 5, 2009 Rep. Bob Filner introduces HR-2254 to restore Agent Orange benefits for Blue Water Navy Vietnam veterans. Companion legislation introduced in Senate.

May 5, 2010 The House of Representatives Veterans Affairs Committee holds hearing on the Agent Orange Equity Act. Congress fails to act on the measure and the legislation dies.

Sept. 23, 2010 The Senate Veterans Affairs Committee holds a hearing on the cost of adding ischemic heart disease, hairy cell leukemia and Parkinson’s disease to the list of illnesses presumed to be connected to Agent Orange exposure. Sen. Jim Webb, D-Va., who served with the Marine Corps in Vietnam, voices skepticism of such Agent Orange compensation.

Sept. 28, 2010 At the request of Senate Veterans Affairs Committee Chairman. Daniel Akaka, D-Hawaii, VA agrees to review the claims from 16,820 Vietnam Brown Water Navy veterans whose Agent Orange claims the agency had rejected without ever reviewing ships logs or other evidence showing these U.S. sailors served in Vietnam’s inland waterways where they may have exposed them to Agent Orange. It’s not clear the VA ever completed the review.

March 18, 2011 Rep. Bob Filner, D-Calif., re-introduces the Agent Orange Equity Act, H.R. 512, to restore VA benefits for Blue Water Navy Vietnam veterans.

April 15, 2011 VA’s regional office in Little Rock, Ark., grants veteran Billy D. Poston – who is represented by The American Legion – service connection for Agent Orange exposure at Fort Chaffee, Ark., in October 1967. The VA decision notes Agent Orange was used on the perimeter of Fort Chaffee from 1967 to 1968.

July 15, 2015 VA estimates it will cost $4.4 billion to provide Agent Orange benefits to Vietnam Blue Water Navy veterans.

Sept. 30, 2015 Congress allows two key provisions of the Agent Orange Act of 1991 to expire that compel the VA secretary to make a decision about granting presumptive benefits for additional illnesses related to herbicide exposure within 180 days of receiving the most recent National Academy of Medicine’s most review of relevant evidence.

March 10, 2016 The National Academy of Science finds sufficient evidence linking herbicide exposure to bladder cancer, hypothyroidism and Parkinson-like symptoms to defoliant exposure. VA fails to add these conditions to the list of diseased presumed connected to Agent Orange despite repeated promises to do so.

Nov. 1, 2017 The White House Office of Management and Budget stops VA Secretary David Shulkin from announcing his decision on whether to provide Agent Orange benefits for veterans with bladder cancer, hypothyroidism and Parkinson-like symptoms. The reason: The cost of those benefits.

May 4, 2018 Legislation to restore Agent Orange benefits for Blue Water Navy veterans is reintroduced in the House of Representatives – but proposed to pay for the benefits by increasing fees veterans and active duty military pay on VA loans.

Sources: The American Legion News Service, The American Legion Magazine archives, National Academy of Sciences – Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine), The New York Times, Military Times, U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, VA, “Waiting for an Army to Die” by Fred Wilcox