Brothers in Arms

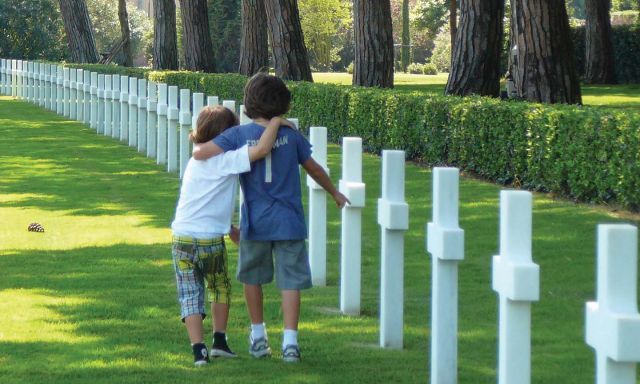

Ten years ago, I visited the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery near Anzio with my wife and young sons. Among the gravestones, we came across two brothers from Iowa buried side by side, Fred and Edgar Wood. As the father of three boys, I found the image of the brothers resting forever together to be especially poignant, and it inspired me to find and tell the stories of all brothers buried side by side in American World War II cemeteries.

More than 90,000 U.S. servicemembers are buried in the 14 American World War II cemeteries around the world. In 243 cases, two brothers are buried side by side. In one case, three brothers rest together.

In 2018, I set out to find the surviving family members of these brothers, to see photos and other artifacts, and to hear firsthand the memories of those left behind.

My journey began at a small house in Buena Vista, Va., where my oldest son and I spoke with Talmadge Claytor, 95, who had served and fought with his two brothers, Eugene and Elwood. At one point during the Battle of the Bulge, the Claytor brothers had the Germans surrounded, he said: one to the north, one to the west, and one to the south. Only Talmadge returned home to tell their tale.

I traveled to 35 states, meeting with 64 families in big cities and small towns all over the country. In Atlanta, Janice Kane told me how her husband, Richard, was recuperating in an Army hospital in France in the spring of 1945 after losing two brothers in the war, John and Norman. When George Patton came by to hand out Purple Hearts, Richard returned his to the famous general, saying he didn’t deserve it. “Why?” Patton asked. “Because I didn’t shed any blood,” he answered. “My brothers did.”

Eileen Cimarron welcomed me into her adobe home in San Felipe Pueblo, N.M., the same one occupied by her grandmother a generation before. Guadalupe “Lupé” Duran lost two sons in the war, Jose and Macedonio. A third son, Isidor, returned but was never the same.

At a dining room table in Omaha, Neb., Donna (Lantow) Fettig recalled being 11 in the autumn of 1944 and riding her bike in the town of Claremore, Okla. Rounding a corner, she saw two women from church walking up her driveway carrying covered dishes. She knew exactly what it meant: someone had died. It was her brother, Norman Lantow, just six months after she’d lost another brother, Robert.

In Salem, Ohio, I asked Margaret Paxson about her two half-brothers killed in the war. She looked at me soberly and said, “When you are all raised by the same single mother, there is no such thing as ‘half’ anything.” She was referring to her mother, Anna Trimmer White, who not only lost Earl and Stanton Trimmer in World War II, but a third son, Carl White Jr., in the Korean War.

In Medford, Mass., Hazel “Summer” Akimoto told me how her husband, Ted, vividly recalled the day in April 1942 when a white bus drove up his street in Los Angeles, accompanied by an Army jeep with a machine gun on the hood. The bus was there to take his family away. Like many second-generation Japanese-Americans, Ted later joined the U.S. Army to escape life in an internment camp, joining his older brothers, Victor and Johnny. Only Ted survived the war.

Finally, I arrived at a towering office building in New York City, where Ted Roosevelt IV told me that when a nosy reporter went to Sagamore Hill in the summer of 1918, he found the former president hugging the horse of his fallen son, Quentin, crying out his name: “Quinny, Quinny, Quinny ....” After World War II, Quentin’s remains were transferred to Normandy American Cemetery to be buried next to his big brother, Ted Roosevelt Jr.

Kevin M. Callahan is author of “Brothers in Arms: Remembering Brothers Buried Side by Side in American World War II Cemeteries” (2020).