On the Front Lines

The American Legion is dedicated to reducing the rate of veteran suicide. As part of the new Be the One campaign, The American Legion Magazine is publishing a two-part series to focus on solutions, provide resources, and educate members and others on how they can support the mission.

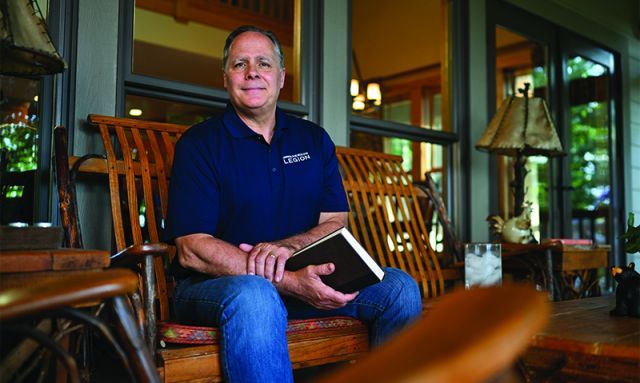

David Rudd conducted his first clinical trial of suicide prevention in the early 1990s. It was a time when the topic of veteran suicide was largely kept quiet, doctors prescribed pills, and the public was in the dark.

Decades later, Rudd has conducted four additional trials, published more than 200 scientific articles on the subject and paved the way for solutions to reduce the rate of veteran suicide. Among the therapies he has helped formulate is brief cognitive behavioral therapy, found to reduce rates of attempted suicide by 60% compared with standard treatment.

“It targets, very specifically, skill development, emotional management, self-management skills, to help people learn to more effectively deal with emotional upset and emotional pain, and ultimately to lower suicide attempt rates and death by suicide,” explains Rudd, a Gulf War Army veteran and a life member of the American Legion Department of Tennessee.

Through the work of Rudd and other leading researchers, more attention is being focused on the veteran suicide epidemic. Still, more must be done. Roughly 20 veterans a day die by suicide.

The American Legion’s new Be the One campaign is shining a light on the crisis, with the goal of empowering veterans, spouses, caregivers, family, friends and others to recognize when a veteran may be at risk and act accordingly.

Solutions

Historically known as shell shock and battle fatigue, post-traumatic stress disorder has burdened servicemembers and veterans since World War I. Rudd first began to explore solutions as an Army psychologist, when he served with the 2nd Armored Division during the Gulf War.

“Suicide behavior, and specifically suicide attempts, were becoming a problem,” he recalls. “They were not as significant a problem as they are today. So we developed the behavioral therapy treatment to try to target that problem.”

Finding solutions for at-risk veterans requires a broad approach. Cognitive therapies work for some, while others benefit from a peer-to-peer approach. Other therapies range from physical activities (hiking, rucking, fishing) to mental (yoga, art, music). More options means more lives saved. Additionally, the research can be used to enact changes that reduce the likelihood of veterans suffering from PTSD in the first place, especially those who were in combat.

Rudd studied the effect of repeated exposure to combat. After one combat deployment, 20% of veterans experienced difficulty in adjustment upon return. The rate increased to 45% after a second deployment and nearly 90% after a third.

“The poor adjustment is people having symptoms,” he explains. “It doesn’t mean you’ve got PTSD. It just means you’re not sleeping well, you’re having intrusive thoughts, you’re having poor dreams, you’re flying off the handle.”

Such data ought to inform policymaking, Rudd says. “In Iraq and Afghanistan, we had people rotate a significant number of times, particularly in special operations. You can expect higher rates of difficulty after repeated exposure.”

Rudd continued his work after separating from the service, founding the National Center for Veteran Studies at the University of Utah.

“We did the first national survey of returning veterans from Iraq,” he says. “A couple of critical things that emerged were not just the issue of depression and post-trauma symptoms, but also substance abuse and suicidality when those problems go untreated. We looked specifically at the reasons veterans weren’t getting treatment.”

Among them: the stigma of seeking help, which is an integral part of the Be the One campaign; a lack of availability of targeted care; and few treatments that were actually available. Also, the overprescribing of medications.

“It’s a medical response to a non-medical problem, which means it’s really a psychological adjustment challenge that people are having. They wanted alternatives to that.”

The research shifted the perception of PTSD and veteran suicide. Non-pharmaceutical treatments are widely available. More veterans openly discuss their struggles. Counseling is encouraged.

Still, more veterans and their loved ones need help. That’s where Rudd anticipates the Be the One campaign making a significant difference.

“I can’t imagine a more appropriate and finer group to be partnering with,” Rudd says. “When educational opportunities are made available, training opportunities are made available, to become aware of not just signs and symptoms of potential problems, but how to effectively respond to those, and help identify resources that might be available for veterans in need, and then help those who are hesitant to access those resources.”

Oftentimes, people “recognize a veteran in pain. But they don’t know, one, how to identify and access good resources for treatment. Two, if they do identify those resources, how to actually help convince a veteran it’s in their best interest to pursue treatment. Treatment hesitancy is arguably the second-biggest problem to stigma.”

Digital therapy

Rudd’s research has opened the door to further exploration for solutions – including a clinical trial of a digital therapeutic aimed at improving access to care, particularly for veterans hesitant about treatment.

Once the FDA approves the digital format, the app will be available. “You can do it individually, with total privacy and confidentiality through your phone. But if you want to engage a clinician, that alternative is available.”

The grant that funded the digital therapy concept also covers work at Ohio State University led by Craig Bryan, one of Rudd’s protégés.

The two men met at Baylor University, where Bryan was getting his doctorate. “From the start of my training and career, he was a mentor,” he says. “Everything he touches turns to gold.”

They stayed in touch when Bryan deployed to Iraq with the Air Force. After he returned to Texas, Rudd hired him at the University of Utah as a research fellow. Bryan moved to the campus and joined the center’s leadership in 2012.

Now director of the Division of Recovery and Resilience at Ohio State, Bryan credits Rudd for fostering innovation and using empirical methods.

“So much in academia is short-term focus, and there’s risk aversion,” he explains. “He looked at new ideas from an investment perspective. If you put enough into it, that could be what it takes for something to succeed, and then you have this really impactful outcome.”

Bryan believes his mentor’s influence will only grow through the Rudd Institute for Veteran and Military Suicide Prevention, dedicated at the University of Memphis in March.

“I think one of the legacies of the Rudd Institute ... is this willingness to not be so afraid of everything,” he says. “That’s when many of our most important advances in medicine occur.”

The future

The Rudd Institute’s mission is to translate the scientific research to clinical service delivery, Rudd says. His vision is to continue various trials, develop new concepts and operate a treatment facility within two years.

“Often veterans simply don’t understand what’s involved in treatment or what the expectations are. It is about learning emotional management skills. That is the heart of what we do.”

What would success look like to Rudd?

“That we actually translate some of what we find into policies that direct how troops are deployed and utilized,” he says. “Then on the other end, we would have broader availability of private alternatives for treatment available to veterans ... not everyone has ready access to a VA facility, nor does everyone want to access a VA facility.” He envisions “a much more extensive, broad-based clinical delivery system nationally, that gave veterans private alternatives, and then trained local practitioners in empirically informed approaches they know work with veterans.”

Henry Howard is deputy director of media and communications for The American Legion.