Answer to the Four Chaplains’ prayers

The week of Feb. 3, American Legion posts across the country will observe Four Chaplains Day, named for four Army chaplains – George L. Fox (Methodist), Alexander D. Goode (Jewish), Clark V. Poling (Reformed), and John P. Washington (Catholic) – who gave up their life jackets so others would live after a U-boat torpedoed their transport in the North Atlantic on Feb. 3, 1943.

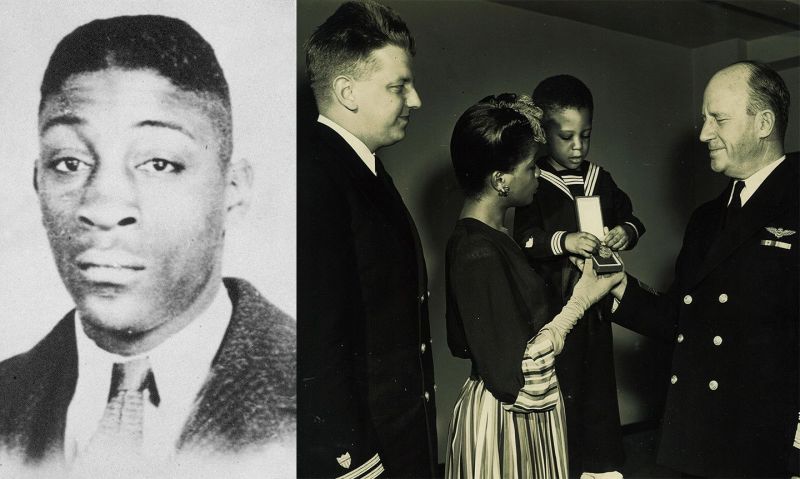

In his 2021 book “The Immortals,” Steven Collis offers a detailed narrative of Dorchester’s sinking, the chaplains’ sacrifice and, for the first time in print, the full story of Charles W. David Jr., the young Black Coast Guard petty officer who, with his shipmates on the escort cutter Comanche, helped rescue 93 of 227 survivors. He died from pneumonia a month later, and was posthumously awarded the Navy & Marine Corps Medal for heroism. In 2013, the Coast Guard named a Sentinel-class cutter for David.

Tell me about the first time you heard the story of the Four Chaplains.

The first time I heard it I was in the office of an attorney who worked on religious freedom matters. He had on his wall a framed copy of the stamp that had been made to honor the Four Chaplains, and he talked about it as a high point in his mind for religious freedom in the United States – people of different beliefs still being able to stay true to who they are but come together for a common good. As I looked at the stamp, I thought it was such a compelling story, and my immediate thought was, “I would love to bring this to life for a new generation.” Not too many years later, when I had an opportunity to put a book proposal together, it was top of mind for me.

What about the story resonates with you?

I am a scholar of religious freedom law, that’s what I do professionally, and I was originally working on a book trying to explain religious freedom law more generally to a lay audience. I wanted to include the story in that book because it really does show what makes America unique. We’re the most religiously and racially diverse country in the history of the world and yet we’re somehow able to live alongside one another in peace. That peace is unique. It’s unique historically and it’s unique in the world today. And we’re able to achieve it largely because of the attitude that the Four Chaplains showed that night, and not even just that night but how they lived their lives serving men prior to their sacrifice. I felt like it was an example that all of us, especially today, could learn from and be trying to emulate more.

There are other books and many websites that tell the story of the Four Chaplains. What were the challenges in trying to do something new?

The biggest challenge was not being too repetitive and also telling it in my own words. I had read everything else written about the chaplains, and I felt like I could tell it in a little bit more of an engaging narrative style. Two, the last book that had been written was in the early 2000s. Books get forgotten, so it was time to revive this story for a new generation. The other goal I set was to try to stick to original sources as much as possible, so I spent days in the (American) Jewish Archives for Alex Goode and then the National Archives and getting my hands on all the official reports, and the journal of the submarine captain … so I could tell the story from the original sources and not simply reframe it the way someone else had told it before.

The big contribution was bringing to life Charles David Jr. No one had really ever told his story. I was well into my research and well into the book before I found him. The most treatment he had gotten was a couple of paragraphs in another book, and that was it. I thought to myself, “This man made as much of a sacrifice as all the chaplains, and he deserves as much of the treatment.” I was at my deadline to get the book published, and I called my editor and said, “Hey, I found this guy. I need you to extend my deadline, get me time to hunt down his family, find out everything I can about him. We need to change the name of the book.” We were going to call it “The Immortal Chaplains.” I said, “He’s not a chaplain. We need to change the name to ‘The Immortals.’” Thankfully my editor was completely on board with that, and Charles David’s family was on board with it.

What surprised you in your research on Charles David’s life?

One thing I thought was really fascinating was that Charles’ family comes from the Caribbean. They emigrated to the United States with a lot of people during the early 1900s and ended up settling in New York City. His father helped build pews for a local church and was a craftsman, and Charles learned those skills. When he opted to enter the military, it was just so different than it is now; there was blatant racial segregation. The only place he could find a position was in the Coast Guard, and in that scenario, the only thing he could really be was a cook or a petty officer. He’s basically been told despite his skills and his natural abilities that he can only progress so far because of the color of his skin. That’s the world they were living in in the 1940s. He was the fifth lowest-ranked man aboard (Comanche) the night Dorchester was sunk, and he had zero obligation to jump into the water and help anybody. Everyone above him should have been doing it, but a lot of people figuratively froze because they were afraid of literally freezing, and they had a hard time jumping into the water. So (David) and a number of the officers jumped in. (He) easily could have said, “It’s not my job. I’m going to go down below and heat up some coffee for people.” In fact, he was in the water again and again trying to save people.

You describe David’s actions as an answer to the chaplains’ prayers. That idea came to me from his granddaughter, whom I interviewed at length. She mentioned to me in passing one time, “You know, I always felt that while the chaplains were on that boat praying that God sent my grandfather as an answer to those prayers.” I thought, “What a compelling way of thinking about this,” and included it in the book. You have four men of different faiths all praying in their own way to God to ask him for help for these men they have sacrificed for, and then you have this very unlikely hero coming and sacrificing himself to save as many of those men as he could. About half the survivors were saved by Charles and the other folks aboard Comanche. Their sacrifice – and his sacrifice in particular, he was the one who died – is really dramatic.

You’ve gotten to know David’s descendants. What’s it meant to them to share his story? He’s been a tremendous source of inspiration for them, and their family has seen generations of success, following in his footsteps. There’s been professors and accountants and law enforcement officers and military personnel and revolutionaries. When he got the award from the Coast Guard, there was a reporter interviewing his widow, and two of her brothers were there. Both of them were talking about how they would love to serve in the military and that they wouldn’t be hesitant to do so. A year after it happened, you can already see his example spilling into the next generation. He’s still someone in their family they’re rightly proud of, as are the families of the chaplains.

Next year is the 80th anniversary of Dorchester’s sinking. Why is the story of the Four Chaplains and Charles David Jr. one we need to hear again? We have the most diverse country – religiously, racially, ethnically – of any country in the world. That diversity can be a huge strength for us, or it can be something we let tear us apart. I think the story of the chaplains and of Charles David Jr. is that we don’t have to let it tear us apart. We can keep those parts of ourselves that are unique to us and not abandon them while also living alongside one another in peace and love while working toward a common goal. I think it’s something we have to constantly relearn in the country; otherwise, it’s going to be very easy to just engage in tribalism and tear ourselves apart. I personally feel like we see that today in the United States. There’s lots of division, there’s partisanship, lots of distrust. We have to get back, I think, to more of the mindset of what these brave men showed. My hope is that more and more people see that story and try to have that same attitude and spirit as they go about their daily lives and their political and public lives.