Grover "Deacon" Jones was the first African-American to be honored at Cooperstown after setting American Legion World Series history in 1951.

In a year in which the coronavirus pandemic cancelled 2020 induction ceremonies at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y., a former American Legion baseball star remains the answer to a trivia question at the hallowed venue.

Grover Williams “Deacon” Jones Jr., was the first African-American to be honored with a plaque at baseball’s top shrine after setting American Legion World Series history in 1951.

A catcher for White Plains, N.Y., Jones helped Post 135 win Sectional A to advance to its first and only ALWS that summer at Detroit's Tiger Stadium.

Though White Plains would lose 11-7 to Los Angeles in the championship game, Jones hit .408 with 19 RBIs, 14 runs scored and five stolen bases in national American Legion Baseball competition that summer to earn American Legion Player of the Year honors. He was the first player from a losing team to win the award that had begun in 1949.

Jones played for Post 135 during its heyday; White Plains’ only state titles came in 1949, 1951 and 1952.

The Los Angeles team that defeated Post 135 in the 1951 ALWS championship game featured a pair of eventual major leaguer infielders in Billy Consolo and Sparky Anderson. Anderson would go on to greater fame as a three-time World Series-winning manager for the Cincinnati Reds (1975 and 1976) and Detroit Tigers (1984), ironically winning the 1984 title in the same stadium in which he won his ALWS title.

Jones, who turned 86 in April, eventually graduated from White Plains High School in 1952 and played basketball and baseball at Ithaca College before signing a professional contract with the Chicago White Sox in 1955.

Two years into his professional career, he spent two years in the military before returning home and advancing to the major leagues.

Jones broke into the majors in 1962 with the White Sox and would eventually spend 11 years in the minors and three years in the majors.

Once his playing career ended in 1969, Jones got into coaching.

Starting as a roving hitting coach for the White Sox minor league system, Jones also managed Appleton, Wis., for one season in 1973 before making a return to the big leagues as Bill Virdon's Houston Astros hitting coach from 1976 to 1982.

After one year with the New York Yankees organization, Jones was back in the major leagues as the San Diego Padres' hitting coaching from 1984 to 1987.

Jones was out of baseball in 1988 but then returned to the sport as a Baltimore Orioles scout for the next 18 seasons.

In a 2008 interview with SABR.org, Jones wondered what his playing career would’ve been like if not for an injury in 1956 spring training.

“I hit a triple against Sandy Koufax in Sarasota, Fla.,” Jones told SABR.org. “I got up and my arm felt funny, and the next day when I got up I couldn’t move it. I went to different doctors. They told me if you have an operation, you won’t be able to throw and play.

“With all due respect, in those days you had to cut through all that muscle and scar tissue. I majored in physiotherapy in college, and I said, ‘No, no. I'm not going to do this.’ I continued to play in the minor leagues. The pain, even off the field, would hurt. My wife would sometimes reach across and touch it, and my shoulder would be hot. I don’t have much patience for people who complain and bitch. You’ve got to deal with it. So I learned to play in pain, as most athletes do, but I still made the big leagues. Rather briefly, but the point was: I made it.”

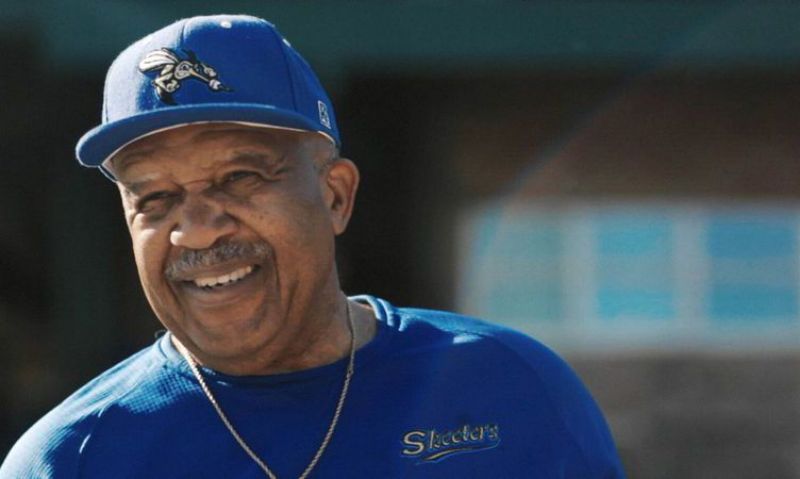

Now living in Houston, Jones was honored in August 2019 by the Sugar Land Skeeters of the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball, which is an independent league not affiliated with major league baseball. Jones has been a special assistant and advisor to the team since it joined the league in 2010.

The Skeeters retired Jones’ No. 4 jersey, the first 1,000 fans at the game received a Jones bobblehead doll and the No. 4 jerseys worn by Sugar Land players were auctioned off for charity at the end of the game.

“At first I was very apprehensive,” Jones told the Sealy (Tex.) News of the honor. “I felt that many people in the city had done enough for me. My wife just told me to embrace it. She reminded me when I was 14 years old I said to my father I saw the black face on TV it was a guy named Jackie Robinson and I said to my daddy, ‘I want to be just like him.’ And he said OK.”

Jones’ advice to potential players is to dream big.

“I tell people all the time about baseball, think about the Hall of Fame, there are a thousand of the best ballplayers in the hall of fame,” Jones told the newspaper. “Nobody talks about how many times they’ve failed. They’re the best! They fail seven times out of 10. Yet they are the best. Life is a series of disappointments, frustrations and failures, interrupted with a few successes. (That's) Deacon's law!”

On April 18 during the coronavirus pandemic, Skeeters team officials arranged for a surprise car parade to celebrate Jones’ 86th birthday while he was at home in quarantine.

“You know anything we can do to honor him,” said Skeeters director of media relations and broadcaster Ryan Posner. “Then somebody on staff threw out the idea, 'Let’s drive by his house and do a parade.’”

For Jones, the gesture gave him a big smile — and a comedic response.

“I got to ask ... ‘What (are) you going to do for my next 86th?’” Jones said.

- Baseball