America's Most Beloved Veterans

One of our nation’s founding fathers, Patrick Henry, put it this way: “The battle, sir, is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave.”

These are the signature characteristics of American veterans. Their strength, vigilance and courage occupy a revered place in the collective conscience of a public made free by the willingness of some to protect all others.

Veterans Day is a time to honor them, living and dead, from the patriots who fought for independence in the late 18th century to the men and women who saved the lives of their fallen comrades on the battlefields of Afghanistan and Iraq. Some came home to become movie stars, professional athletes, generals and presidents. Others, like the four chaplains of different faiths who went down with a sinking troop ship after passing out life jackets to everyone else they could, would not live to see their legacies honored.

In May 2014, The American Legion Magazine asked its readers, website visitors and social media followers to select from a list of 100 beloved U.S. veterans. More than 70,000 votes were cast. The choices span our nation’s lifetime.

Here are the top 25, with descriptions written by authors, experts, historians and, in a few cases, those who knew them best. After you’ve read them, click through the rest of the gallery for links to some of the Web’s best biographies of these celebrated Americans.

Top 25

Top 26-100

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Audie Murphy

He was an unlikely hero. Born into a life of crushing poverty in Texas, Audie Murphy was so scrawny when he tried to enlist after Pearl Harbor that the Marine Corps and the paratroopers wouldn’t take him. He joined the infantry. Even there, his officers suggested he accept a non-combat role. Instead, Murphy became a front-line warrior, fighting his way through Sicily, up the boot of Italy, and into France and Germany. He is one of history’s most decorated combat veterans. Through it all, he felt the same sense of “weary indifference” he experienced when he killed his first enemy soldiers in Sicily. Nor he wasn’t fearless. On the battlefield, “fear is right there beside you,” he wrote.

Murphy was an everyman who found and lost himself in war. His Medal of Honor citation praised his “indomitable courage,” but he paid a heavy price for his heroism. Even after he became a movie star, Murphy fought demons war had created within him.

“Before the war, I’d get excited and enthused about a lot of things,” he told John Huston, who directed him in “The Red Badge of Courage,” “but not anymore.” He suffered from nightmares, slept with a gun under his pillow and gambled recklessly. He titled his autobiography “To Hell and Back,” but it seems a part of Murphy never returned from the hell of combat. Such are the sacrifices heroes make.

– Tom Huntington, contributing editor to America in WWII magazine and author of “Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

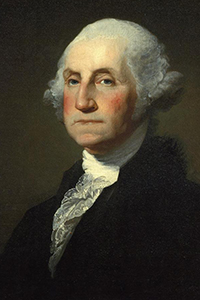

George Washington

In June 1775, when George Washington accepted the daunting assignment of commanding Congress’ forces in the fight for American independence from Britain, he was already a seasoned veteran. During the 1750s, while in his 20s, as colonel of the Virginia Regiment, he’d learned hard lessons in leadership fighting the French and their Indian allies in savage frontier skirmishes.

That experience was crucial during the Revolutionary War, when Washington faced the far greater challenge of maintaining the armed struggle against the British Empire with an army that was typically understrength, underfunded, and all too often unappreciated by the politicians and civilians it was fighting for.

For eight long years of punishing campaigning, Washington inspired the officers and men of the Continental Army through his personal example of courage, determination and integrity, always sharing their hardships and dangers.

The worst situations brought out the best in Washington’s character. Most famously, despite a discouraging series of defeats around New York in 1776, before that year was over he re-crossed the Delaware River in a devastating counterattack, scoring victories at Trenton, and soon after at Princeton, that revived the patriot cause.

As first president, George Washington remains celebrated as the father of his country. By forging the Continental Army into a tough, well-trained force of professionals, he deserves equal recognition as the true father of the U.S. Army.

– Stephen Brumwell, author of “George Washington: Gentleman Warrior”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Theodore Roosevelt

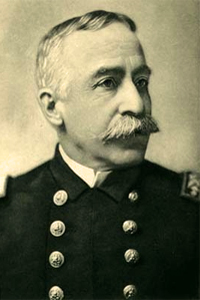

Theodore Roosevelt’s ranking in the top tier of beloved American veterans parallels his top-tier ranking (fourth or higher in polls of historians) among U.S. presidents. The great affection for Roosevelt as a veteran is a product of his heroic battlefield performance in Cuba in 1898 and his extremely successful efforts to bolster U.S. military power between 1897 and the end of his life in 1919, along with his exemplary character, endearing personality and other monumental accomplishments.

Soon after the Spanish-American War broke out in the spring of 1898, TR resigned from his position as assistant secretary of the Navy to organize and lead into combat a regiment of soldiers, the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry. On July 1, 1898, Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” joined other U.S. Army regiments in driving entrenched and well-armed Spanish forces from the San Juan Heights. Notwithstanding his innumerable subsequent achievements, Roosevelt would never cease to remember that July day as his “crowded hour,” as “the great day of my life.”

In the aftermath of Roosevelt’s heroic victory, the entire U.S. chain of command in Cuba recommended the colonel for the Medal of Honor. These officers’ recommendation was denied due primarily to the incompetence and the hostility toward TR of Secretary of War Russell Alger, whose department’s many serious blunders Roosevelt had criticized. This glaring injustice was at long last rectified when Roosevelt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Bill Clinton during a ceremony in the Roosevelt Room of the White House in 2001.

As president, Roosevelt built up the U.S. Navy, making it the world’s second most powerful, and, to the great benefit of the United States and the world as a whole, managed to institutionalize a naval building program for the long term. The 14-month world cruise of Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet proved to be both a magnificent spectacle and a brilliant diplomatic maneuver, and has undoubtedly contributed even further to his standing as a particularly beloved veteran.

– William N. Tilchin, history professor at Boston University, author of “Theodore Roosevelt and the British Empire: A Study in Presidential Statecraft,” and editor of the quarterly Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal

America's Most Beloved Veterans

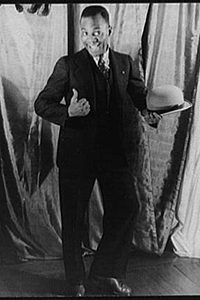

Alvin York

My grandfather, Alvin C. York, was one of 10 children born and raised in a rural area of Tennessee. He learned to shoot early in life and always had a rifle or pistol handy. He hunted and shot in matches on Saturdays with his father. That experience served him well when he faced an overwhelming enemy force in France’s Argonne Forest on Oct. 8, 1918.

When the fight was over, York and seven others had captured 132 Germans (128 soldiers and four officers). The other seven had been pinned down behind cover by machine-gun fire from the surrounding high ground and were unable to assist him in the fight. At one point, a German officer and five men charged him with fixed bayonets. He had only a half of a clip left in his rifle, so he pulled his pistol – a .45 automatic – and shot the last one first. He worked his way up until he’d shot the last one, who was leading the charge.

For his actions, York was awarded the Medal of Honor, the French Croix de Guerre and numerous other medals. He returned to a hero’s welcome in the United States after spending several months in Europe waiting to go home.During this time, he attended the inaugural meeting of The American Legion as a representative of his unit, the 82nd “All American” Division.

He received many lucrative offers, but he turned them down because he felt he would be selling his uniform and service overseas. He returned to the mountains of Tennessee to marry his sweetheart, Miss Gracie, and raise his family on a farm in the Wolf River Valley of Pall Mall.

Because of his travels, my grandfather treasured education, which he had not had the privilege of receiving as a child and young man. He devoted time and effort to building and running a high school, the York Agricultural Institute. He worked tirelessly for the children of Fentress County and to bring education to the rural area where he was raised. On two occasions, he mortgaged his own home to make sure the school stayed open. He knew that the world was a larger place than the mountains and that to be competitive the children of his area needed an education.

When asked, my grandfather said that he’d like to be remembered for his work in education. In the late 1930s, he was persuaded to allow a movie to be made about his life and war exploits, as the world was once again facing war and patriotism in the United States was low. He was told that this would help the United States, so he agreed as long as the film was kept factual and did not “Hollywoodize” his story. “Sergeant York,” starring Gary Cooper, was released in 1941.

At the start of World War II, York volunteered for duty with the Army. Due to his age and physical ability he did not see active duty, but was commissioned a colonel in the Signal Corps (for which he wore no uniform or received pay) and traveled around the country selling war bonds. A stroke left him partially paralyzed until his death on Sept. 2, 1964. He is buried in the family cemetery, close to where he was born and raised.

His life’s work and legacy live on through the York Historic State Park,the York Agricultural Institute and the Sgt. York Patriotic Foundation. Their mission is “legacy in action” by promoting educational opportunities and honoring veterans. Through this work, my grandfather’s story teaches the next generation about history and heroes. More than his actions on the battlefield, the man behind the medals makes Alvin York’s legacy so intriguing.

– Gerald E. York, retired Army colonel

America's Most Beloved Veterans

George Patton

Nearly 70 years after Gen. George S. Patton’s death, he remains one of America’s most popular military figures. Why? The answer is simple: Patton was a winner who knew how to convince his soldiers that they were winners too.

The Germans tested Patton’s leadership early in his World War II command. He had taken over the U.S. Army’s II Corps after its disastrous performance at the Battle of the Kasserine Pass in February 1943. He was in charge less than a month when the Deutsches Afrika Korps challenged his command at El Guettar. Patton’s soldiers whipped the panzers, and it was the U.S. Army’s first major victory against the German Army in Europe.

Patton’s success continued. During the summer of 1943, leading the Seventh Army during the invasion of Sicily, his soldiers captured or killed more than 13,000 enemy soldiers while sustaining a fraction of those casualties in return. After Sicily, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Patton to lead the Third Army in northwest Europe.

On Aug. 1, 1944, Patton’s Third Army rocketed out of Normandy and raced across France in record time, crippling the German Army. In late September, his divisions crushed the German Fifth Panzer Army at the Battle of Arracourt. In December, while the rest of the Allied armies reeled from the Battle of the Bulge, the Third Army was counterattacking. Asked how long it would take his soldiers to relieve Bastogne, Patton promised that his men would be ready to move in fewer than 48 hours. Senior leaders scoffed, but he proved them wrong, and his men relieved the 101st Airborne the day after Christmas.

Everywhere Patton went, he won. The men who served under him loved him, while his enemies respected and feared him. After the war, many German generals claimed he was the best Allied general. They were right.

– Leo Barron, author of “Patton at the Battle of the Bulge: How the General’s Tanks Turned the Tide at Bastogne”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Dwight Eisenhower

“If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.” So wrote Dwight David Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force landing in Normandy on June 6, 1944. On the eve of the greatest military endeavor in history, Eisenhower understood the deep responsibility of command. The decision to commit 150,000 men, 5,000 ships and countless aircraft to the liberation of Western Europe from Nazi oppression was his. In the face of a determined enemy and horrific weather, he told his assembled lieutenants, “OK, we’ll go!”

From a humble beginning in the heartland of America, Eisenhower rose to the highest echelon of military command, proved himself the master of coalition warfare during World War II, and engendering the confidence of the American people in his ability to lead them through the earliest days of the Cold War, was twice elected president. He never shrank from a challenge but discharged his duty with an earnest will and an unforgettably broad grin. It was easy to like Ike.

Dwight Eisenhower placed the success of the mission ahead of any personal reward or gain. In doing so, he defined leadership by example, and he shouldered the great weight of responsibility that came with it like no other individual in the 20th century.

– Michael Haskew, author of “West Point 1915: Eisenhower, Bradley, and the Class the Stars Fell On”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Norman Schwarzkopf

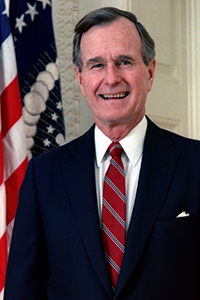

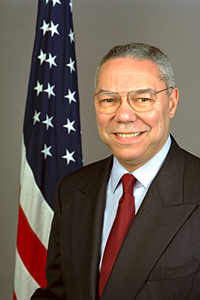

In 1988, when I was President Reagan’s national security adviser, we were selecting a new commander for Central Command. The initial Pentagon recommendation was a superb Navy admiral. But we wondered if an admiral was the right choice.

The Iran-Iraq war had just ended in a cease-fire, and the huge Iraqi army now had the flexibility to look for trouble elsewhere It seemed to us that if trouble broke out and we got involved, it would primarily be a joint ground conflict, and it seemed more logical to have a ground commander. Norm was selected to be that commander.

A year later, I became chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Norm and I finally worked together under then-Secretary Dick Cheney. The end of the Soviet Union was in sight. We had to get ready to reduce our Cold War size, change our strategy and give back to the American people.

You can imagine the bureaucratic challenges we faced. Of all the terrific combatant commanders we had at that time, it was Gen. Schwarzkopf who had the greatest understanding of the need to change. He was an indispensible adviser as we made our case for a sensible reduction to a smaller but fully capable force.

Then, on Aug. 2, 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Norm and his staff had been considering the possibility of an Iraq attack in the region and had been preparing contingency plans.

We assembled with President Bush and his war cabinet at Camp David. After much discussion, Norm laid out the contingency plans he was working on, now updated in light of the invasion.

Although execution would be challenging, the plan he laid out that day eventually became Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. Armed with that plan, President Bush was able to say to the world, “This will not stand, this aggression against Kuwait.”

It would take me hours to describe all that Norm and his troops did in the six months that followed. With contributions from three dozen countries, he created and led a force of almost 700,000 troops to drive the Iraqis out of Kuwait. It’s hard to believe now that there were even Egyptian and Syrian forces under Norm’s command. The international community was united.

Norm’s diplomatic skills and experience from living in the area as a young man made him an expert in working with the leaders in the region. He could drink tea and sit with the best of them.

Schwarzkopf gained the confidence of the coalition leaders, and they were full partners and allies in the campaign. Of vital importance, he also gained the full confidence of the American people, who saw young men and women who were trained, competent and disciplined, washing away any lingering Vietnam-era images.

Norm and I would often discuss at night, “Where did we get such terrific kids? They are the ones who solve the problems and make it all happen. They will win the battle.” Of course, we got them where we always did: from the cities, towns, farms and factories of America. The troops looked so good that I was getting all kinds of mail recommending we reinstate the draft and make all our kids as squared away as them.

Norm and the troops came home to parades and well-deserved adulation. He then retired. He no longer belonged just to the Army, but to the nation, and he found new ways to serve it with distinction.

The reality is that when anyone thinks of Desert Storm, they think of Stormin’ Norman, the Bear, the Commander – the tough, brusque guy with a heart of care and kindness, who was the personification of the troops he loved and led to victory. He was a larger-than-life figure who by his performance, his articulateness and his brilliant strategy lit up the world.

– Colin Powell, retired four-star Army general and former U.S. secretary of state

America's Most Beloved Veterans

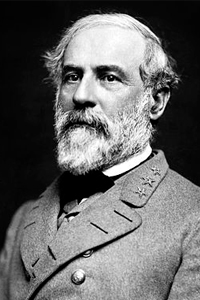

Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee revealed his military promise in 1829, finishing second in his class at West Point without a single demerit. After duty as an engineering officer at remote outposts, he served in the Mexican War and was commended repeatedly for his actions. His engineering feats solidified his position as perhaps the foremost officer in the Army. Following service as superintendent of West Point, he was deployed with the U.S. Cavalry to the western plains.

During the Civil War, Lee organized his Army of Northern Virginia from a mixed tapestry of troops into one of the most formidable and effective fighting forces ever known. He did this despite a severe disparity of numbers and chronic shortages of basic supplies, such as food, clothing and medical supplies. Always considerate of his men, he surrendered at Appomattox rather than expose them to more bloodshed when he faced the inevitable.

Early in his adult life, Lee became the consummate Christian soldier. He thanked the Almighty for his numerous victories and often took defeat as a rebuke from above. Throughout his military career, his family – especially his invalided wife – remained his foremost concern.

Lee considered that his most important work was done during reconstruction as he sought to instill among Southerners a lack of bitterness and a sense of union with the reunited country. He worked diligently as president of Washington College to prepare young men of the South for a productive future while instilling in each one of them his own gentlemanly and Christian attributes.

It is quite easy for veterans to admire him and try to emulate such a soldier and citizen.

– Donald Hopkins, Mississippi surgeon, Vietnam War veteran, and author of “Robert E. Lee in War and Peace: The Photographic History of a Confederate and American Icon”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Jimmy Doolittle

“His deeds are in sharp contrast to his name,” the Miami Daily News once wrote of aviation pioneer and Medal of Honor recipient Jimmy Doolittle (1896-1993). Though born in California, he spent his formative years in Alaska, where his father unsuccessfully hunted gold. The 5-foot-4-inch Doolittle learned as a youth to compensate for his small size by raising his fists, boxing professionally through high school and college at the University of California School of Mines.

A gifted racing and stunt pilot with an ear-to-ear grin, the brilliant Doolittle earned his master’s and doctorate degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was not only the first pilot to fly cross-country in a single day but the first to take off, pilot a plane and land solely on instruments, a feat he accomplished in a hooded cockpit. He later worked for Shell Oil and was instrumental in developing 100-octane fuel.

Doolittle is most known for his planning and execution of the famed April 18, 1942, bombing raid against Tokyo that bears his name. The audacious assault prompted Japan’s military leaders to commit to the invasion of Midway, which ended in disaster and proved the pivotal turning point of the Pacific War. Doolittle went on to command the 12th, 15th and 8th Air Forces. At the war’s end, he returned to Shell Oil, where he served as a vice president and a director.

– James M. Scott, author of the forthcoming “Target Tokyo: Jimmy Doolittle and the Raid That Avenged Pearl Harbor”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

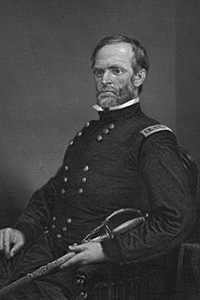

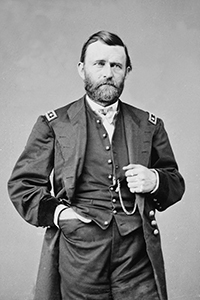

Ulysses Grant

Most Americans today could use a history lesson about the Northern general who won the Civil War. By the time of his death in 1885, Ulysses S. Grant had earned the gratitude of millions who believed he was both the general who saved the Union and the president who made sure that it stayed together.

Grant was born in modest circumstances, graduated from West Point in 1841 and enjoyed brief acclaim during the Mexican-American War. In 1861, he answered President Abraham Lincoln‘s call for volunteers and rapidly won fame in the Western Theater, scoring decisive and morale-raising victories at Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg and Chattanooga.

When Lincoln tapped him in early 1864 to be the leading general, Grant directed victories that vindicated his strategic vision, guaranteeing his president’s re-election. The Union’s hero was praised for the magnanimous terms of surrender that he offered, and Gen. Robert E. Lee accepted, at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. Shortly afterward, he became the first four-star general in U.S. history, remaining as head of the Army until nominated for president by the Republican Party in 1868. Grant swept to victory with his famous campaign slogan, “Let us have peace,” and was re-elected in 1872.

Later, stricken ill with cancer, Grant wrote his “Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant.” With those volumes, Grant ensured his legacy as one of America’s greatest generals and most essential presidents.

– Joan Waugh, author of “U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Jimmy Stewart

The patriotism of James “Jimmy” Maitland Stewart (1908-1997), one of America’s most beloved actors, was grounded in his smalltown upbringing and family military service history reaching back to the Civil War. Rejected as underweight by his draft board, he went on a crash-eating program to bulk up. On March 22, 1941, one month after winning his best actor Oscar for his role as a tabloid journalist in “The Philadelphia Story,” Stewart was accepted into the U.S. Army Air Corps – the first major movie star to enter the military.

Stewart then found himself fighting stateside duty training pilots, narrating films and selling war bonds. In November 1943, Capt. Jimmy Stewart achieved his combat theater goal, arriving in England as a B-24 Liberator pilot. In September 1945, he returned home as a colonel and a decorated hero, having received the Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster, the Croix de Guerre with Palm, and other medals.

Stewart entered the Air Force Reserve and retired after 27 years of service with the rank of brigadier general, the highest-ranking Hollywood actor to serve in uniform. The on-screen honest, straightforward and humble “everyman” persona audiences loved was the same off-screen. His postwar movie contracts contained a clause that prevented studios from capitalizing on his military and war records.

– Dwight Jon Zimmerman, president of the Military Writers Society of America, whose books include “Lincoln’s Last Days” and “Uncommon Valor: The Medal of Honor and the Warriors Who Earned It in Afghanistan and Iraq”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

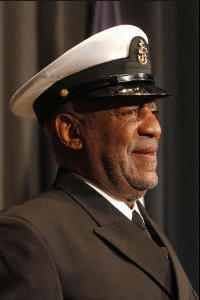

Doris "Dorie" Miller

Sometimes the war hero is a cook, third class – like Doris “Dorie” Miller, his ship’s heavyweight boxing champ and Navy Cross recipient, who dashed to the bridge to save the life of his mortally wounded skipper, Capt. Mervyn S. Bennion, during the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor.

With no training for the task, Miller also manned a .50-caliber Browning anti-aircraft machine gun until it ran out of ammunition, perhaps even downing one of the attacking Japanese aircraft. “I think I got one of those Jap planes,” he later said. “They were diving pretty close to us.”

Close is right. All told, USS West Virginia was hit by five aircraft torpedoes and two armor-piercing bombs. More than 100 officers and men were killed in the attack.

Interrupted from his laundry rounds that fateful morning, the 22-year-old farmer’s son from Waco, Texas, found his assigned battle station wrecked, went to the bridge and carried the badly wounded Bennion to a first aid station, then manned the machine gun, all the while under fire.

Often considered the first African-American hero of World War II, Doris Miller was one of the 646 Americans lost when a single torpedo from a Japanese submarine sank the U.S. escort carrier Liscome Bay near the Gilbert Islands in the Pacific on Nov. 24, 1943.

In 2010, Miller was the only enlisted man among four distinguished sailors from the 20th century honored by a panel of U.S. postage stamps.

– C. Brian Kelly, co-author of “Best Little Stories from World War II” and “Best Little Stories from World War I”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Michael Murphy

I’m often asked why Michael’s legacy of service and sacrifice stands out among so many. As his father, I like to think it has less to do with his actions on June 28, 2005 – when he exposed himself to enemy fire to send a call for help and fought to his death so that a member of his squad could escape, for which he posthumously received the first Medal of Honor for actions in Afghanistan – and more about how Michael represents the spirit, honor and courage of all our fallen heroes.

Michael was, first and foremost, a team player, part of a team of Navy SEALs. As much as he fought and died for his teammates, they fought and died for him. Therefore, I see Michael as that “everyman” in our armed forces, embodying service, spirit, honor, courage and willingness to sacrifice for friends, teammates and country.

This wasn’t something instilled in Michael as a SEAL but was part of his character as he was growing up. As a 13-year-old playing Little League baseball, he once hit a game-winning home run in the last inning. As he came into home plate, his teammates were there to congratulate him, telling him that he’d won the game for the team. Michael told them that they won the game together, because if others hadn’t gotten on base, he wouldn’t have made it to bat. I was amazed at his maturity – amazed that he thought more of his team than himself at such a young age.

When Americans hear Michael’s story or see the movie “Lone Survivor,” they’re hearing and seeing the story of every American hero – a story of their willingness to protect and save their teammates, even at the cost of their own lives. A dad couldn’t be any prouder of such a legacy.

– Daniel J. Murphy, combat-wounded Vietnam War veteran who served with the 25th Infantry Division in Tay Ninh province, and father of Navy Lt. Michael P. Murphy

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Eddie Rickenbacker

The son of poor German-speaking Swiss immigrants, Edward Vernon Rickenbacker overcame the specter of his father’s violent death, a debilitating eye injury and accusations of being a German spy to become the American ace of aces in World War I and a Medal of Honor recipient. His extraordinary capabilities, unshakable patriotism and steadfast perseverance enabled the grade-school dropout to circumvent the college degree requirement for pilots, shoot down 26 German aircraft and take command of the 94th Aero Squadron, which under his leadership grew into America’s most successful air unit.

He went on to start a premier car company, own the Indianapolis Speedway and found Eastern Airlines. During World War II, Rickenbacker’s harrowing three-week ordeal aboard a life raft with only rainwater and the food they could catch in the central Pacific showed a weary nation by example that it had the fortitude to survive a war on two fronts.

Part daredevil, part tinkerer, cool risk manager, improviser and showman, Rickenbacker helped forge a new, and particularly American, brand of heroism that would serve as a model for following generations of explorers, adventurers and warriors, from Jimmy Doolittle and Charles Lindbergh to Chuck Yeager and John Glenn.

– John F. Ross, author of “Enduring Courage: Ace Pilot Eddie Rickenbacker and the Dawn of the Age of Speed”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Chris Kyle

Chris Kyle was a lot of things to a lot of people: Navy SEAL, legendary U.S. military sniper, decorated veteran of the Iraq war, beloved husband and father.

Yet of everything that can be said about Chris, the word that stands out most is one he would never have used to describe himself: hero. Not in the sense of a man who rushed into a hail of bullets to rescue others (he did). Not in the sense that his wife and children understand (no one will ever know that depth of Chris).

Chris Kyle is a hero because in every interaction he had with a person, it was clear that he had an unwavering faith. And he truly cared for and valued everyone he ever met.

There was no pretense, no “personality,” to Chris Kyle. There was only the person – genuine, faithful, real. He had a sense of security and self-assuredness that are only found in a deep faith in Jesus Christ.

And for that, we can all say, “Thank you, Chris Kyle.”

– Ed Young, senior pastor of Fellowship Church in Grapevine, Texas, and author of “The Creative Leader”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

The Four Chaplains

On Feb. 3, 1943, four Army chaplains – Father John P. Washington, Rabbi Alexander D. Goode, and the Revs. George L. Fox and Clark V. Poling – gave up their life jackets on a sinking Army transport in the North Atlantic so that others might live.

Of the 902 soldiers, Navy armed guard, ship’s crew and civilian passengers on board the Dorchester, only 230 survived. They have told us of the chaplains’ efforts to restore calm in a hopeless and chaotic situation, and how they were last seen at the ship’s stern, arms linked in prayer.

The survivors’ testimony and the chaplains’ bravery are enshrined at the Chapel of Four Chaplains in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, where the Chapel Memorial Foundation honors acts of selfless service nationwide in memory of the Four Chaplains and crew of USAT Dorchester.

– Louis A. Cavaliere, retired Navy captain and chairman of the Chapel of Four Chaplains, and Christine Beady, the chapel’s executive director

America's Most Beloved Veterans

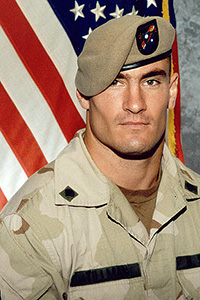

Pat Tillman

The day after 9/11, Arizona Cardinals safety Pat Tillman (left) told a reporter, “At times like this you stop and think about just how good we have it, what kind of system we live in, and the freedoms we are allowed. A lot of my family has gone and fought in wars, and I really haven’t done a damn thing.”

The next spring, Pat put his NFL career on hold to enlist in the Army with his brother, Kevin. Assigned to the 75th Ranger Regiment at Fort Lewis, Wash., they served in Iraq in 2003 and in Afghanistan in 2004.

On April 22, 2004, Pat’s unit was ambushed while traveling through the rugged canyon terrain of eastern Afghanistan. His heroic efforts to provide cover for fellow soldiers as they escaped led to his death via friendly fire. A decade later, Pat’s story of service before self has become synonymous with American sacrifice and patriotism.

– Marie Tillman, president and co-founder, Pat Tillman Foundation

Read more about Pat Tillman here.

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Douglas MacArthur

What is true for Gen. Douglas MacArthur, that you either love him or hate him, isn’t true for any other great American military commander – or veteran.

George Washington is extolled as a leader who shaped a motley group of militiamen into a Continental Army, Ulysses S. Grant is admired for forcing Robert E. Lee’s surrender, John Pershing is renowned for his stubbornness, and George Marshall and Dwight Eisenhower are celebrated as the architects of victory in World War II. All of these, including Lee, are part of the pantheon of “great” American military leaders, entering our history nearly without blemish.

Celebrated for his record at West Point and one of the most decorated commanders of World War I, MacArthur is remembered for his July 1932 decision to wield federal troops against peaceful Bonus March demonstrators. The subsequent pictures of MacArthur’s troops beating hapless veterans forever stained his reputation. As did his April 1951 defiance of President Harry Truman, which led to his dismissal – and his reputation as an officer who defied civilian control.

But MacArthur was also a great military commander with a record of accomplishment nearly unequaled by any other World War II leader. His defense of the Philippines, conquest of New Guinea, reduction of the Japanese fortress at Rabaul, and victories at Leyte and Luzon propelled him into the front ranks of America’s greatest wartime strategists. His subsequent administration of postwar Japan, where he served as America’s “shogun,” sealed his, and America’s, legacy as conquerers without animus. And despite his disagreements with Truman, his landing at Inchon during the Korean War is credited with reversing a near defeat.

Vain, egotistical and self-promoting, MacArthur’s final act revealed his understanding of war and of the American people. “Never get involved in a land war in Asia,” he told John F. Kennedy in July 1961. Kennedy admired his advice and vowed to follow it, though sadly his successor didn’t.

Love him or hate him, Douglas MacArthur left his mark as a soldier, commander and veteran who refuses to fade away.

– Mark Perry, author of “The Most Dangerous Man In America: The Making of Douglas MacArthur”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

John F. Kennedy

Americans remember John F. Kennedy as a president, but long before that, he was a decorated veteran. The military record JFK compiled assisted him enormously on the road to the White House.

A sickly child and teenager, Kennedy was nonetheless determined to serve in the military. He refused to change his plans despite failing physicals to enter both the Army and the Navy. While some scions used family connections to avoid wearing the uniform, Kennedy used his contacts to override the results of the physical exams so he could enlist in October 1941, two months before Pearl Harbor. Later – when he suspected his father was pulling strings to keep him away from combat – young Kennedy bypassed his old man and used a U.S. senator to get him transferred to the South Pacific on a PT boat in the Solomon Islands, where battles were already raging. Instead of the safe postings offered Kennedy stateside and in the Panama Canal Zone, where he could easily have waited out the war, Kennedy insisted on active duty at the front lines.

There is little question that the defining experience of Kennedy’s pre-presidential life was the sinking of PT-109, the vessel commanded by young Lt. j.g. Kennedy. JFK had been a privileged bon vivant, the son of one of the nation’s wealthiest and most powerful men, former Ambassador to Great Britain Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. His world changed Aug. 2, 1943, when the Japanese destroyer Amagiri cut his PT boat in half; young Kennedy was tested in a way that few ever are.

Two PT-109 crewmen were killed, but 11 others, including Kennedy, survived. He helped round up his men and bring them to the listing hull, where they clung desperately for nine hours. Realizing they would have to organize their own rescue, they swam for the deserted, 70-yard-wide Plum Pudding Island. Despite his severely injured back, Kennedy stayed on course for five grueling hours while towing a badly burned crewman by clenching the ties of his life jacket between his teeth. Over the next few days, JFK reconnoitered nearby islands in search of aid and provisions before establishing contact with two native islanders who were working as scouts for the Allies. Kennedy convinced them to deliver a coconut he had etched with an SOS message to the closest Allied base. Rescue followed two days later. On June 12, 1944, Kennedy received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for heroism. When asked how he had become a hero, JFK quipped, “It was involuntary. They sank my boat.”

Elected president by a narrow margin in 1960, Kennedy proved a friend of fellow veterans and U.S. military forces, and a fierce advocate of preparedness. He established the Navy SEALs in 1962, authorized the “Green Beret” as the official headgear for all U.S. Army Special Forces, and dramatically increased the defense budget, the number of Navy ships and Army divisions, and the nation’s stockpile of nuclear weapons. As JFK explained on Jan. 20, 1961, “For only when our arms are sufficient beyond doubt can we be certain beyond doubt that they will never be employed.”

As with tens of thousands of veterans, Kennedy’s war wounds continued to plague him throughout the years. His back had sustained such major injury that he underwent two operations in the 1950s while a U.S. senator – and nearly died in 1954. As president, he was on crutches from time to time. “At least one-half of the days he spent on this earth were days of intense physical pain,” said his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, after JFK’s death.

JFK’s sturdy Oval Office rocking chair, which helped ease the muscle strains, became a symbol of his Presidency. (He also kept the carved coconut that had saved his and his crew’s lives on his desk.) A photographer captured the rocker’s removal from the Oval Office shortly after Kennedy's assassination on Nov. 22, 1963. That empty chair symbolized the void a grieving public felt.

It was Kennedy’s military service, and his tragic death, that gave full meaning to his famous inaugural declaration: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” This statement is a timeless reminder to Americans of John F. Kennedy, veteran and president, and it is a precious legacy that those in the military, past and present, have carried on by means of their sacrifices for the nation.

– Larry J. Sabato, author of “The Kennedy Half-Century: The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Billy Mitchell

Billy Mitchell is one of the most iconic and controversial figures in U.S. military history. His achievements have been overshadowed by his political antics and flamboyant personality, the legends surrounding the origins of the Air Force and the politics of strategic bombing.

While Mitchell posthumously received a special medal for his outstanding pioneer service and foresight in the field of military aviation, his court-martial for insubordination – after accusing Army and Navy leaders of “almost treasonable administration of the national defense” – is one of the most extraordinary in the annals of U.S. military justice.

Lionized by the Air Force and demonized by the Navy, Mitchell has been described as a “heroic lone patriot fighting” against bureaucracy for the good of the country, on the one hand, and an “egotistical charlatan” more interested in grandstanding than the future of airpower, on the other.

Mitchell is often portrayed as the founder of the Air Force and the creator of strategic bombing. He was neither. Ironically, his World War I service is often overlooked and underplayed. In September 1918, he planned and led nearly 1,500 American and Allied aircraft at St. Mihiel in one of history’s first coordinated air-ground offensives, and by the end of the war was commanding all U.S. Army air combat units in France. Indeed, it is difficult to see how the Air Service’s success and acclaim would have been possible without Mitchell.

– Thomas Wildenberg, author of “Billy Mitchell’s War with the Navy: The Interwar Rivalry Over Air Power”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

John Paul Jones

The “American way of war” may have been, since the days of Gen. Ulysses Grant, to overwhelm the enemy with superior firepower. But the American military has also, from its earliest days, prized resourcefulness and daring against great odds. John Paul Jones embodies the latter tradition. In the Revolutionary War, the fledgling, tiny Continental Navy was no match for Great Britain’s Royal Navy, which ruled the seas with a hundred massive ships of the line. The American rebels had a few frigates and sloops. For most of the war, the Continental Navy remained blockaded in port.

Not John Paul Jones. He understood that the battle must be carried into the enemy’s home waters. First aboard the sloop Providence, he raided British fishing grounds in Nova Scotia, then took his newly built sloop Ranger into British waters, raiding the port of Whitehaven and then sailing to his native Scotland in an unsuccessful attempt to kidnap the Earl of Selkirk. (Jones’ men appropriated the Earl’s silver, which Jones, who saw himself as an officer and a gentleman, later returned.) They defeated HMS Drake in a rousing single-ship action and made off with dozens of warships in hot pursuit. No naval force had attacked British soil in over a century.

Jones’ great moment of glory came a year later, on Sept. 23, 1779, when he took the frigate Bonhomme Richard into battle against a superior British warship, HMS Serapis. “I wish to have no connection with any ship that does not sail fast, for I intend to go in harm’s way,” Jones famously wrote, but it is an irony of history that he sailed into his most critical battle in an old, slow tub.

Still, he grappled with the enemy, and when the British captain asked him if was ready to surrender, Jones is said to have replied, with words that have gone down through the ages, “I have not yet begun to fight!” About two hours later, after losing half his men in intense fighting, the British captain struck his colors.

Jones’ triumph over a better armed, better trained British man of war shocked the British people. Embarrassed, their government tried to make the most of the defeat by granting the captain a knighthood for putting up a brave fight against the “pirate Jones.” Jones, who had a sense of humor, was amused by his foe’s effort to salvage some honor. When he heard that Captain Pearson was now “Sir Richard,” Jones slyly remarked, “Were I only able to make him a Lord someday.”

Jones has been called “the father of the American Navy,” and he lies in a tomb at the U.S. Naval Academy. He gave the Navy its age-old spirit: indomitable and bold.

– Evan Thomas, author of “John Paul Jones: Sailor, Hero, Father of the American Navy”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

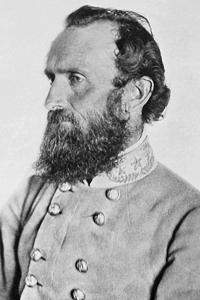

Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson

If you want to see why Stonewall Jackson endures as a figure of history and legend, take a look at the poem “Barbara Fritchie,” written by the prominent American poet John Greenleaf Whittier in 1864, which became a national sensation two years after Jackson’s death. In it, Whittier tells how Jackson ordered his men to shoot down an American flag in Frederick, Md. But when an old woman took the flag in her hands, Jackson ordered his men to stand down: “Who touches a hair of yon gray head / Dies like a dog! March on! he said.”

None of this ever happened, but to the Northern nation – to the wartime nation – the incident was as good as documented fact. What it said was that Jackson was a gentleman and a Christian and a decent person, certainly, in spite of his role in killing and maiming tens of thousands of young Northern men. But it also said that he was, fundamentally, an American. He had, after all, fought heroically for his country in the Mexican War. In Whittier’s poem, it was his Americanness that had stirred in him and redeemed him.

What happened after Jackson’s death was the first great national outpouring of grief for a fallen leader in the country’s history. Though it was overshadowed by Lincoln’s death two years later, Jackson’s death touched the hearts of every household in the South, and prompted many admiring testimonials in the North. “I rejoice at Stonewall Jackson’s death as a gain to our cause,” wrote Union Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, “and yet in my soldier’s heart I cannot but see him as the best soldier in all of this war, and grieve at his untimely end.”

– S.C. Gwynne, author of “Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

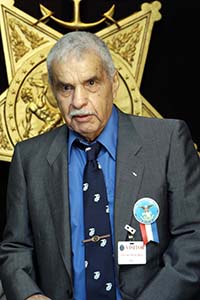

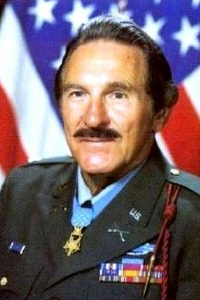

Bruce Crandall

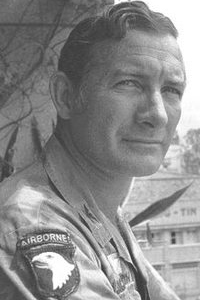

Col. Bruce “Ol’ Snake” Crandall is the bravest, craziest, funniest helicopter pilot I ever met in 43 years of going to war.

On Nov. 14, 1965, during the Vietnam War’s Battle of Ia Drang, Snake and his wingman, Maj. Ed “Too Tall to Fly” Freeman, led 16 slick Hueys into Landing Zone X-Ray again and again – hauling in 1st Battalion 7th Cavalry troops, hauling out their wounded, and hauling in resupplies of ammunition, water and medical supplies. When the LZ got so hot that Lt. Col. Hal Moore closed it, “Snake” and “Too Tall” just kept coming.

Both of them earned the Medals of Honor they received for their actions. Scores of the wounded are alive today because of their heroism. “Too Tall” Ed died in August 2008, breaking up a partnership and friendship that lasted half a century. “Snake” Crandall carries on the mission at 81, traveling the United States and war zones around the world, visiting our troops.

– Joseph L. Galloway, co-author with Harold Moore of “We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young” and “We Are Soldiers Still: A Journey Back to the Battlefields of Vietnam”

Read more about Bruce Crandall here and here.

Watch Bruce Crandall's Medal of Honor story here.

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Omar Bradley

Omar Bradley led the American D-Day invasion, single-handedly planned the Normandy breakout, and engineered the Allied charge across Europe. But he never stood at the head of the parades through liberated towns, preferring to let his subordinates take the accolades. It was one of the ways he was able to get the most from his generals, from the brilliant but mercurial George S. Patton to the far less inspired Courtney Hodges.

Honored in the Army as a master tactician, Bradley is probably best known to the public as the “GI General.” The nickname was coined by Ernie Pyle during the Sicily campaign, where Pyle recounted the general’s humble ways and his concern for his troops, even as Bradley dodged bullets on the front line. That reputation was cemented by a two-year stint as head of the Veterans Administration following Germany’s surrender. Asked by President Truman to head the scandal-ridden agency, Bradley reshaped it in two years, vastly improving its efficiency as well as its reputation.

Returning to the Army, Bradley became its chief, then the first head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He remained active into the 1970s and is the last man to have held the five-star rank.

Bradley’s personal style – laid back and respectful no matter whom he was dealing with – was joined to an active intellect and a command of detail. From revising doctrine and training to initiating the officers candidate program, Bradley left an indelible mark on the prewar Army. It was his intimate knowledge of that army, as well as his combat and strategic skills, that led to his successes during the war and helped ensure the American victory.

– Jim DeFelice, author of “Omar Bradley: General at War”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

Lewis "Chesty" Puller

He acquired the nickname “Chesty” for the way in which he carried his sub-6-foot frame while on the march. He stands as an icon and an enduring prototype of the modern Marine rifleman.

In prayer every night with his son, the proud son of Virginia invoked the names of his two boyhood heroes, Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. His grandfather fell to Union fire in the skirmish at Kelly’s Ford. But it was against America’s foreign enemies that “Chesty” Puller made his name. He became the most decorated leatherneck in history, with a Silver Star, a Distinguished Service Cross and five Navy Crosses (Nicaragua 1930 and 1932, Guadalcanal 1942, Cape Gloucester 1943, and Chosin Reservoir 1950) among the many ribbons on his left breast.

He had a gift for leading men. He could break down complex tasks so that anyone could learn them. “I can take any dumb son of a bitch and teach him to shoot,” he declared.

His talents on the battlefield were paired with a unique gift for memorable aphorism. Enveloped by Chinese troops in Korea, he told his regiment, “We’ve been looking for the enemy for several days now. We’ve finally found them. We are surrounded. That simplifies the problem of getting to these people and killing them.”

On the day he retired, at 57, he thanked the enlisted men and junior officers who had made possible his rise from private to three-star general. And today, at Parris Island and Camp Pendleton, Marine Corps boots return the salute every night: “Good night, Chesty Puller, wherever you are!”

For his never-quit spirit, good humor and ferocity to lead, Puller’s name resonates with us today.

– James D. Hornfischer, author of “Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal”

America's Most Beloved Veterans

John Basilone

America's Most Beloved Veterans