Randolph Kelly, a foreign-born vet, finally naturalized after 30 years in the military and a near-lifetime of believing he was a citizen.

When Randolph Kelly moved with his family from Belize to the United States in 1968, he felt an immediate attachment to American culture - so much that he decided to enlist in the U.S. Army four years later.

“I just wanted to be a great American even though I wasn’t from here originally," he says.

That decision was the genesis of a 30-year military career that spanned three hostility periods and saw him rise to the rank of Sergeant Major. He left the Army in 2002 with an honorable discharge and a promising post-service life ahead of him.

But one thing was missing: Unbeknownst to him, he never became a true U.S. citizen.

Kelly, now 62 and living in Mission Hidalgo, Texas, is one of many foreign-born veterans who have surfaced in recent years with sometimes-illustrious military careers, but no U.S. citizenship to show for it. Veterans like him used their lawful permanent resident status to enlist - oftentimes during war periods when recruiters needed "warm bodies" and were not asking many questions - and manage to never become naturalized even after decades of service.

Many of them share the misconception that their service confers citizenship, says Elizabeth Ricci, an immigration law attorney out of Tallahassee, Fla., who represents veterans like Kelly pro bono in their quests to gain citizenship.

"They need to understand, their service does not give them citizenship," Ricci says. "The oath of allegiance for naturalization and the oath of enlistment have similar wording. So a lot of people get confused by that."

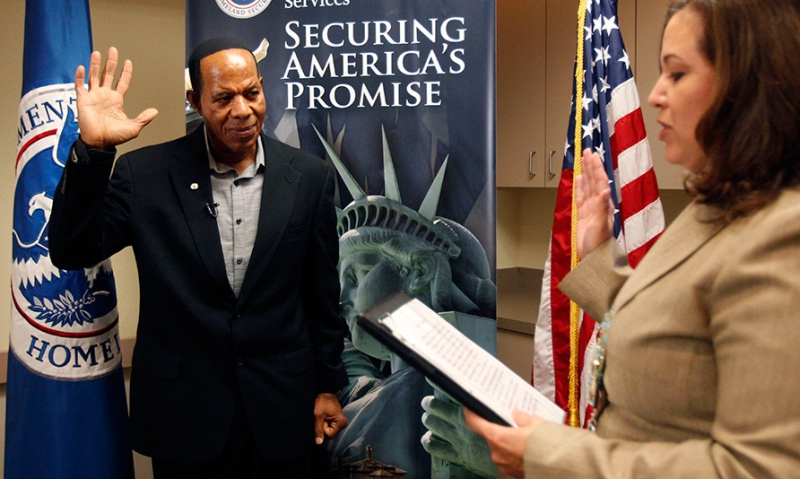

Last month, Ricci stood with Kelly at his naturalization ceremony at the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services Office in Harlingen, Texas, where Kelly finally became a U.S. citizen.

She took his case as part of her campaign to reach out to the estimated 640,000 foreign-born veterans in the United States. The crucial thing, she says, is that none of these veterans assume that they are U.S. citizens without adequate documentation.

"Even if they believe they are a citizen, they need to verify it," she says. "They can do that by showing their passport or their naturalization certificate. If they don’t have either of those things, and if they didn’t take a (naturalization) oath either before a judge or an immigration officer, chances are they are not a citizen and they just mistakenly believe they are."

Ricci, who is a second-generation American herself, often works with The American Legion Department of Florida to track down and spread her message to foreign-born veterans like Kelly. Her goal, she says, is to help them avoid assumptions about their citizenship, and make them realize that there is a cost-free, fast-track naturalization option available to them if they served during a period of hostility.

"Even if you don’t have a green card, if you’ve served during any of the hostility periods, you can jump straight to citizenship," she says.

Normally, permanent immigrants must reside lawfully in the United States for at least five years to receive citizenship. But U.S. law provides an expedited naturalization process for noncitizens who served honorably in the U.S. military during World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, or any other period of hostility declared by the president. In July of 2002, President George W. Bush signed an executive order declaring a period of hostility that began on Sept. 11 and is still open today.

Those laws, Ricci says, waive the $680 naturalization fee for foreign-born veterans and servicemembers, and grant U.S. citizenship in eight to 10 months.

"It's crucial that veterans realize the fee waiver also applies to them and not just active-duty military," Ricci says.

In recent years, Ricci has helped about 10 veterans like Kelly who have lived sometimes for decades under the false belief that their enlistment oath and service in the military naturalized them. Some have been open-and-shut cases, while others have been fairly high profile, including Cuban-born veteran Mario Hernandez, who served in the U.S. Army and even worked for the federal government for 22 years without ever becoming a citizen.

Hernandez says he's voted in every major election since 1976. And he worked for many years as the supervisor for the U.S. Bureau of Prisons, often transporting notorious prisoners such as Timothy McVeigh. But it wasn't until he decided to take a cruise with his family last year that someone pointed out to him, at the age of 58, that he wasn't a U.S. citizen.

"I’ve done this job where I had background checks every year, and my fingerprints are on file at D.C. I’ve transported people and carried people," Hernandez says. "I’ve been all over the place. And then they told me that they don’t have a record of me being an American citizen… It was just like, ‘How can this be?’"

Ricci says Hernandez' story is a common one. "It always comes up when they decide to take a cruise," she says. And many of them, like Greek-born Vietnam veteran Michael Michelis, were led to believe that they'd become U.S. citizens when they signed on the dotted line of their military contracts.

"When I first got in, they asked me if I was a citizen," says Michelis, who became a citizen earlier this year with Ricci's help. "I was told if I signed up and got an honorable discharge, I'd be a citizen."

Ricci estimates that there could be hundreds or even thousands more foreign-born veterans and servicemembers in the United States who falsely believe they are naturalized. She says it's important that any veterans born in a different country locate proper documentation of their citizenship because it is a felony to make misrepresentations about citizenship.

American Legion service officers, she says, should remain vigilant, as well. "Any time they see a foreign-born vet they should check to see if he or she has a naturalization certificate or proof of citizenship," she says.

The path to naturalization for them is easy to traverse and highly rewarding, as has been the case for Kelly, who finally gets to say he is "a great American" almost 50 years after he enlisted in the Army.

"It means the world… I can vote. I could become part of the process," Kelly says. "I could run for office if I wanted to. Now I feel that I don’t have to look behind my back. I can look a man in his face and say, ‘You know what? I am an American.'"

- Citizenship