Award-winning author opens conference with grim outlook for the future of a unified West.

Internationally acclaimed author and journalist Ian Buruma recently met with Sir Michael Howard, a British World War II combat veteran and renowned military historian. Buruma wanted to know from the 93-year-old scholar his take on the Brexit vote in Great Britain to break away from the European Union.

“He answered, in a tone of resigned melancholy, that he saw it as an acceleration of the disintegration of the postwar order set up by the United States and helped by Britain,” Buruma told hundreds gathered Thursday for the opening session of the International Conference on World War II in New Orleans, put on by the National WWII Museum. “The world he fought for, he feels, is in the process of disintegrating. And, I don’t think this happened this year. This is one thing we cannot blame on Donald Trump.”

Buruma told the group that the 1941 Atlantic Charter, which laid the ideological foundation for a postwar world four years before the fighting was over, envisioned a future of the West that would be built on the removal of trade barriers, self-determination, democracy, openness and human rights. Through those principles would arise alliances built on unification, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the United Nations and, ultimately, the European Union.

“There was a liberal consensus very much set up in the war by the United States, with Britain as a junior partner, that was built on the openness of the Atlantic Charter – open trade, democracy, equality and open societies – all of that guaranteed by the United States through NATO and other international institutions,” Buruma said. “Now, this consensus has lasted pretty well… until today. It’s lasted a very long time. I think it’s now in very grave danger of collapsing.”

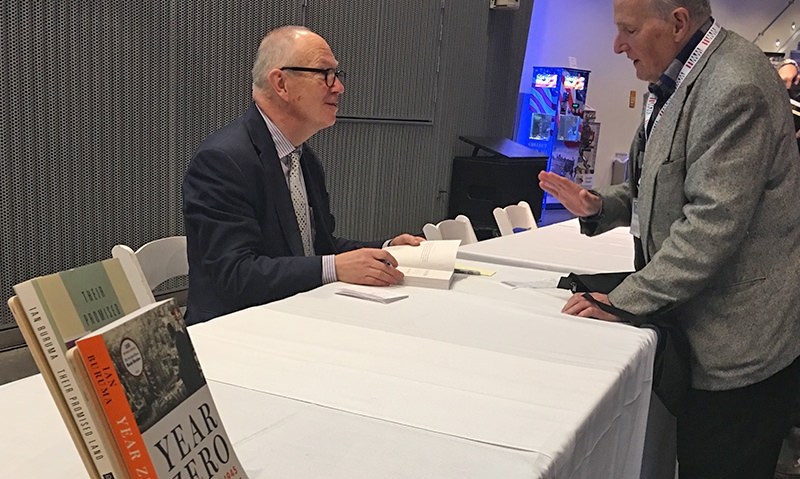

Author of “Year Zero: A History of 1945” about the emergence of the West in the aftermath of World War II and many other books, Buruma said Europe and the western Allies were by no means in full agreement about the path out of the war’s horrors. He said French President Charles De Gaulle created “a great myth” that all of France was supportive of the Allied invasion and victory over Nazi Germany. Another schism De Gaulle faced was between western and communist idealism, the two forces that ultimately defeated the Nazis, each with its own starkly opposed concept of how society should operate.

The German propaganda machine was also advancing a vision for life after World War II, promoting racial unification and a Europe free of the Jewish people, communists and others who stood in the way of Nazi domination. “German propaganda was all about uniting Europe from their point of view, uniting against Bolshevism, and against Jewish plutocracy,” Buruma said. “The Germans had a very different view of what a unified Europe would look like.”

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Great Britain Prime Minister Winston Churchill were not in agreement about aspects of the Atlantic Charter, “specifically on the question of self-determination,” Buruma said. “Churchill understood very well what this could mean. Roosevelt was not a fan of colonial rule.

“The idea of European unification really came from the ashes of World War II,” Buruma said. “Winston Churchill himself even said of a united states in Europe, only this way will hundreds of millions of toilers be able to regain the simple joys and hopes that make life worth living. Unification of the world was an ideal that was held by the people at the time. People were thinking that way. The United Nations, of course, came from that.”

As the Cold War supplanted World War II in the decades after 1945, the western concept of unification through freedom and opportunity eventually – after millions more were killed in the Korean War, Vietnam and elsewhere around the world – won out. When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, effectively ending the Soviet Union and leaving the United States as the world’s lone superpower, “we all celebrated,” Buruma said. “But it had consequences. One is that it was no longer necessary to have a kind of western counter to Soviet communism. We didn’t have to persuade anyone anymore. It also tainted everything associated with collective idealism.”

The Cold War victory and the rise of western prestige in the late 1980s also coincided with a prevailing need for U.S. military and economic strength elsewhere around the planet to maintain security, stability and unification. “One of the problems of the postwar order is it created a dependency on the United States,” Buruma said.

- Honor & Remembrance