Bataan Death March survivor describes how he has coped with a life of post-traumatic stress.

Lester Tenney spent three and a half years as prisoner of the Japanese during World War II. He lived through the infamous Bataan Death March. He watched friends and comrades tortured, starved, executed without reason and worked to death. His fellow soldiers would break their own bones or burn themselves to get two or three days of relief from 12-hour shifts they faced as coal-mine slaves in deadly Japanese prison camps.

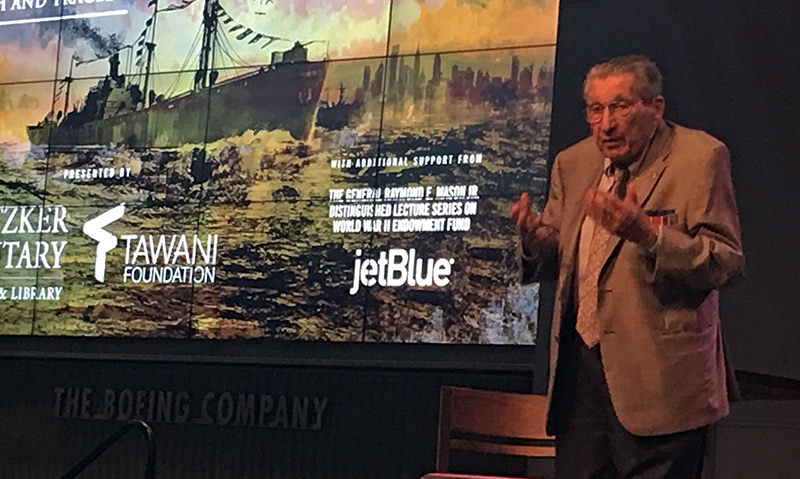

“I was there,” he told hundreds gathered Saturday night for the George P. Shultz Forum on World Affairs at the end of the International Conference on WWII at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. He was also there when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending his ordeal.

That’s when an unexpected kind of trouble began, he explained.

First, as the former POWs were coming home on the same ship, believing they were to arrive to fanfare and fun in San Francisco, they were informed they would instead port in Seattle where they were simply offloaded, ordered to get into a truck and move along. “Where was the music? Where was someone to say welcome home? No one was there.” Next, he discovered that his wife had married another man thinking Tenney had died because he was listed as missing in action. Then, when he tried to reconnect with friends at home in Kentucky, they were no longer around, many still in the service, working elsewhere or onto college and careers. The girls with whom he danced were now married, pregnant and raising children. His hatred of the Japanese grew as events unfolded.

The abrupt shift to civilian life was what exacerbated in him a condition defined at the time only as “battle fatigue” or “shell shock.” He later understood that he suffered with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “It was a sickness, a plain and ordinary sickness,” Tenney told attendees. “We were sick. Post-traumatic stress is something you don’t get over. You have to learn to deal with it, but you don’t get over it. I didn’t overcome it right away.”

An early step in his postwar life was to see in person the wife he had never divorced or left widowed. He forgave her, told her she did the right thing by remarrying, and moved on. “I had to see her,” he said. “I told her I dreamt of her for three and a half years so, ‘You did save my life, whether you know it or not.’”

With no wife or friends, his condition worsened, but he pushed through life, working intensely in multiple businesses. “I came home to no one, and that happened to a lot of the men who came home.”

He later met a young Japanese student who explained the culture that had made the Japanese so merciless during the war. The student said he knew it was wrong, as did most of his generation, and his age group was not of that thinking. “How could I hate this boy? He did nothing wrong. I was able to forgive the Japanese. Being able to forgive relieved me of all the anxiety that I had. I was able to become a human being again. It made a different life for me.”

He had tried to get help for his psychological condition after the war. “I read this report in a newspaper that there was a group of veteran doctors who said they could inject the brain with medicine to help overcome post-traumatic stress. Then they said, ‘What we can do is give them therapy.’ What kind of therapy? Shock treatment. They said if you got shock treatment three days a week, it will help you.”

He couldn’t believe it. “You mean I came home from prison camp to get shock treatments and injections to my brain? I said there’s got to be something better than that.”

He decided it was up to him to work through his condition, battling misery with its opposite. He decided to forgive those who had done him wrong and to try to understand them. He worked hard, trying to project a positive attitude. He began to intentionally pursue happiness and appreciate it. “Once you learn to be happy, once you learn that life is beautiful, then we can deal with these things. These things are not going to overcome us. They are not going to put us in our grave. No way. They cannot do that to us. Forgive. Learn to forgive, and learn to understand other people, other cultures.”

Tenney said he came to understand that in the wartime Japanese culture, there was no such forgiving, no surrender and no sorrow expressed. “That is the code of conduct that these soldiers were raised with. They hated because they were taught to hate.” Understanding it, he was able to ultimately reconcile his feelings for the Japanese.

Fifteen years passed between his discharge and marriage to wife Betty, who proved critical to his long-term recovery. “She had to live with all of this that I was going through. She helped me immensely. There is no way I could be 96 without her.”

Tenney said he thinks VA is still struggling with PTSD treatment, although of his own VA care “I have nothing but good things to say.” He told the group that PTSD needs to be evaluated in a different way, to attach different levels of severity to it, understanding it affects no two people alike. “I think it has a lot to do with who you are,” he said. “How do you evaluate stress?”

His second book, “The Courage to Remember: PTSD – from Trauma to Triumph,” was published in 2014. His critically acclaimed first book, “My Hitch in Hell,” came out in 2007 and examines the physical abuse of the Bataan Death March and the POW experience in Japan.

He concluded his message to the audience in New Orleans Saturday night by giving every attendee a copy of “The Courage to Remember” and urged any veterans suffering with PTSD to read it. He said if he can improve just one life by sharing the way he learned to manage the psychological effects of a horrific wartime experience, followed by a painful homecoming, that’s all that matters to him, at the age of 96.

- Honor & Remembrance