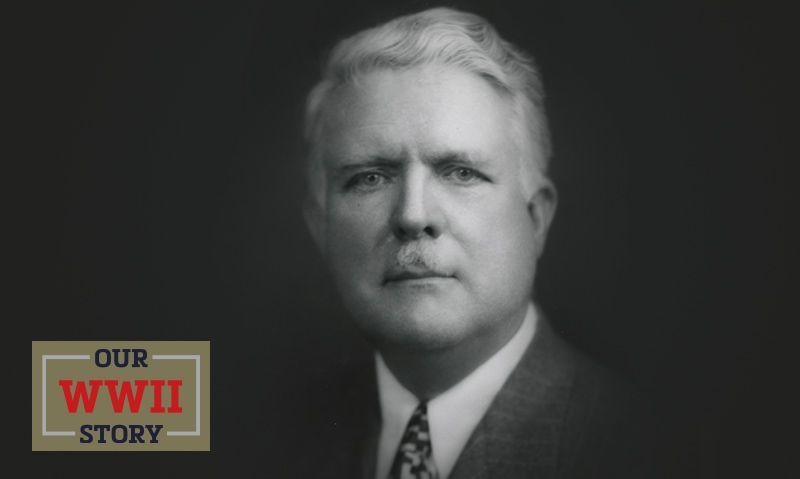

The influential John Thomas Taylor served in Patton’s Army before he made amendments to the GI Bill.

John Thomas Taylor joined the Army on April 6, 1917, the day the United States entered World War I. He saw combat in the 27th and 29th Divisions and rose to the rank of captain. Following the armistice, he attended The American Legion’s formative Paris Caucus of March 15-17, 1919, and less than a year later, he saw President Woodrow Wilson sign The American Legion’s federal charter.

Thus began more than 30 years of veterans advocacy for the Washington-based attorney who served as The American Legion Legislative Committee’s vice chairman and division director. Once described as the most influential lobbyist on Capitol Hill, he ushered more than 650 legislative initiatives into law for veterans and was featured on the cover of the Jan. 31, 1935, issue of Time Magazine.

Three months before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Gen. George Marshall called Taylor back to service, promoted him to colonel and made him assistant director of public relations for the U.S. Army. After the United States entered World War II, he was assigned to Gen. George Patton’s 7th Army and participated in the Operation Torch landings of North Africa in 1942. He continued to serve in Sicily, Italy and France and was promoted to brigadier general.

During his second stint in uniform, he missed out on much of the negotiation and debate over the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, the GI Bill of Rights, considered the most significant legislation advanced in The American Legion’s history.

Following the war, however, Taylor had his say on it. He returned to Washington, resumed his position as American Legion national Legislative Division director and went right to work to improve the package of education and home-loan benefits that transformed the U.S. economy after World War II. According to his American Legion obituary, Taylor “doffed his uniform… buckled on pearl-gray spats, seized his Malacca cane and charged up Washington's Capitol Hill with fire in his eye. For days, he would confront the lawmakers, in lobby and cloakroom and restaurant, and he gave no quarter. As a result of his labors, the GI Bill was amended in 10 places.”

Taylor continued to work for The American Legion until 1950. He died of a heart attack at age 79 on May 20, 1965, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, thus silencing “the golden voice of a Washington lawyer who at one time had 17,500 clients,” his obituary stated. “He knew every member of Congress and called many of them by their first names. He helped guide more than 650 veterans’ bills through Congress and spearheaded The American Legion’s fight in obtaining benefits of more than $13 billion for ex-servicemen.”

Having served in two world wars, fighting for adjusted compensation for World War I veterans, producing hundreds of thousands of petitions from Legionnaires in support of the organization’s initiatives, amending the GI Bill and working to develop national veterans cemeteries, he had accumulated many photos, awards, medals, souvenirs and other mementoes, the most important of which, he said, was his American Legion membership button.

- Honor & Remembrance