Virginia Legionnaire survives Liberty ship disaster in Mediterranean.

The ship named after William Jackson Palmer, railroad man of the mid-19th century and Union Army cavalry general during the Civil War, was laid down in the Permanente Metals No. 1 yard in Richmond, Calif., on Sept. 25, 1943, and launched just 24 days later on Oct. 18. It was one of the 2,710 Liberty ships built in the United States during World War II, the ships that carried the products of the “Arsenal of Democracy” to allies and America’s own far-flung forces all over the world. Some credit Liberty ships with being the key factor for victory in the war.

On the opposite coast near Gretna, Va., Elmer Cocke had just finished high school. He was the son of a farmer, and because he was engaged in farming was deferred from the draft. But in 1944, the United States was desperate for more soldiers and sailors, and began to tighten deferments. Elmer could sense that he was about to be drafted. His close friends were keen to join the United States Maritime Service – the Merchant Marine – and that is how Elmer learned of that option.

To borrow a phrase from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, William J. Palmer and Elmer Cocke had “a rendezvous with destiny.”

Elmer reported to the U.S. Maritime Training Station at Sheepshead Bay, N.Y., in November 1944 and went through six weeks of indoctrination and training, which was divided into a preliminary training branch and six branches of advanced instruction: Deck; Engine; Cooks and Bakers; Pursers; Hospital Corps; and Chief Steward's Course. Apprentice seamen could apply for admission to any of the courses except Chief Steward. In addition, they could compete for entry into the U. S. Maritime Service Radio School or the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy.

Elmer was 20 when his young wife, Hilda, visited him while he was at Sheepshead Bay, riding a Trailways bus to the big city, the one-way ticket purchased with the last penny she had. Elmer was paid $18 a month as an apprentice seaman, and she had counted on him for the return ticket and whatever expenses they might have in New York. Finally, after seeing the sights in the city, Elmer was flat broke – they had but two dimes to their name, but one more site was on their agenda: Coney Island. The subway cost 5 cents then, so the first 10 cents got them to the park, and the last 10 cents brought them back. But to get bus fare home, Hilda hocked her wristwatch in a Brooklyn pawn shop. (Elmer later went back to that establishment and redeemed the watch. It wouldn’t be the last time he played close to the edge.)

Elmer and his friends from Gretna opted for the U.S. Maritime Service Radio School and reported to that installation on Gallops Island in Boston Harbor. Instruction was intense: Eight hours a day learning radio theory, construction and Morse code. He said later, “Learning Morse Code was the most difficult thing I ever did.” He discovered that the dots and dashes come so fast that there isn’t time to think, e.g., “Dit-dah, well that’s an A.” To be able to understand it at the necessary speed, the process is almost subconscious; you must instantly recognize dit-dah-dit as an R and dah-dit-dah as a K. They were tested at the end of each week, and those who didn’t copy and send at the ever-increasing required speed were made to spend weekends in practice and doing housekeeping chores. Elmer succeeded. His send-and-receive rate reached an accurate 30 words per minute. He was graduated and promoted to Warrant Officer, USMS, and now earned the princely sum of $22 per month.

William J. Palmer had worked its way to New York, and Elmer joined it in the late spring of 1945. The war was over in Europe by then, but not in the Pacific. The ship was loaded with 460 horses and set sail for the Mediterranean, calling first at Gibraltar, then Barre. It sailed independently, not in a convoy, but zig-zagged darken ship on the chance that a rogue U-boat might still be prowling in the Atlantic. Orders kept changing but its final destination was Trieste.

Whether the captain inadvertently sailed into a known minefield or through an uncharted one isn’t clearly established, nor is it known whose mine it was – German, Italian or British – but whatever its origin, it and William J. Palmer met near noon on Aug. 4, 1945, in the Gulf of Trieste in the Adriatic Sea, between Barre and Trieste.

Elmer was one of three radio officers and happened to be on watch in the radio shack, just aft of the bridge, when the mine detonated. He recalled, “It was the loudest bang I ever heard!” He was thrown into the overhead of the radio room by the blast, and both main radios were wrecked and put out of commission. The senior radio officer came to the radio room, relieved Elmer, and managed to get off a distress signal using an emergency radio, a crude crystal set. A British naval unit acknowledged the call.

Elmer was assigned to lifeboat No. 4 on the port side. The ship took an immediate port list, but the boat was swung out, only to be obstructed from becoming waterborne by an accommodation ladder that had been dislodged by the explosion and had swung out in the path of the boat. Elmer jumped down on the accommodation ladder and helped move it away. When the boat became waterborne, it became apparent that the man who had been assigned to free the man ropes had not done his duty, so the boat was entered by means of a Jacob’s ladder dropped from the main deck. There was great confusion; some men helped, and some were helpless and frozen with fear. The men in the boat soon realized that their feet were sloshing around in ankle-deep water. The man assigned to put the drain plug in had failed to do his duty. Elmer noted that the ship had not regularly conducted fire and lifeboat drills.

Finally, when the boat was boarded by those assigned to it and cast off the rapidly sinking ship, the survivors found the oars had been tied down to the seats and the knots needed to be cut. The only man with a knife was frozen with fear and could not move. The knife was taken from him, the oars cut loose and the boat pulled away from the ship. Elmer remembers how the water poured over the side of the ship as it began to go down. He remembers the roar of the water, the sound, as it poured like a waterfall over the port gunwale of William J. Palmer. He remembers horses swimming and trying to get into the boats. So much water had entered the lifeboat through the drain before it was plugged that the boat was unstable and the occupants had to bail furiously lest they capsize. Asked if he was fearful, he immediately said, “Yes! I was afraid, and any man who says he wasn’t is a liar!” According to Elmer, the ship sank within 10 minutes, stern first. The small British ship that came to their rescue was reluctant to approach, but stayed on the horizon due to concern about mines. All four boats were tied together and the one that had an engine pulled them to the rescue ship, which they boarded as night began to fall.

Not a single man was lost in abandoning ship nor in the explosion, and somehow six horses of the 460 survived. Elmer had only the clothes on his back and nothing else, but he was alive and in one piece. The British ship took the crew to Trieste, and they were boarded in a hotel for two days. A British radio man invited the three radio officers to lunch the third day. Upon returning to the hotel, they found all their shipmates had left for Venice. Someone in authority gave the three a truck, a pistol, a prisoner of war to deliver and directions to Venice, where they rejoined their mates, delivered the prisoner and waited two weeks.

Elmer and the others were given a change of clothes by the Brits, and he and his fellows then boarded a ship for Naples that was occupied by the U.S. Army. The stay in Naples was about three weeks long. Elmer took a draw of $10 against his wages from the captain; the shipwrecked mariners had no other money but made use of a daily issue of a pack of cigarettes by the Army for 6 cents. They could sell the cigarettes to local urchins as young as 6 for $2 a pack. With this windfall they bought clothes. While in Naples they learned that a secret weapon, an atomic bomb, had been dropped on a Japanese city; a few days later came word that, at last, the war was over. Elmer boarded a New York-bound ship in Naples and as soon as it arrived, found himself once again a working radio officer on another Liberty ship headed for Marseilles, France, empty and in ballast. This ship was fitted with rudimentary bunks in the holds, stacks as high as five, which allowed the ship to load hundreds of victorious soldiers, happy to be returning home to America by any means. Elmer recalls the smell that emanated from the holds as hundreds of those soldiers were terribly seasick during the voyage, which lasted about two weeks.

That trip over, Elmer was paid off and discharged in January 1946 in New York, to return to Gretna and Hilda and resume life on the farm. When asked if he’d do it all again if he could go back to 1944, he said he’d probably wait to be drafted.

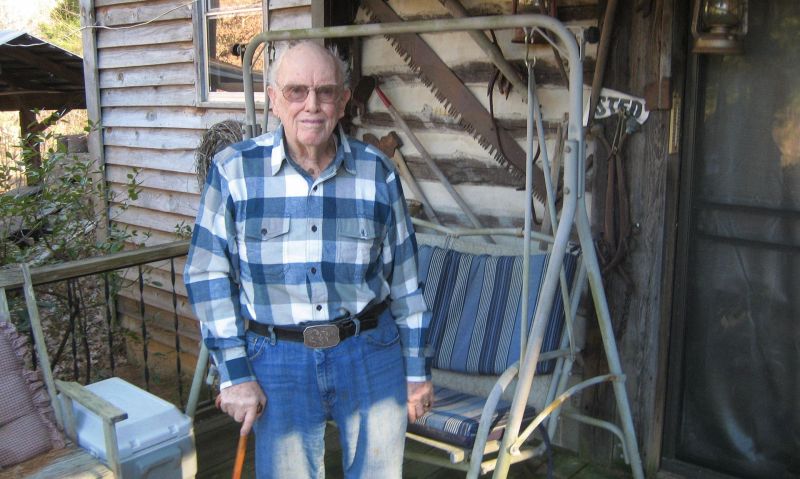

Elmer Cocke, a member of American Legion Post 232 in Gretna, will reach his 98th birthday in April 2022. He drives his car and still hunts deer on his farm near Gretna that he inherited and added to, buying adjacent properties over the years. While previously living in South Carolina, he converted a flue-cured tobacco barn on that property into a hunting lodge overlooking a pond which he would occasionally visit. He now lives there, independently, in that former well-built tobacco barn, full-time.

Enemy action in World War II resulted in the loss of 1,768 merchant ships sunk, damaged beyond repair, captured or detained. Over 8,300 men lost their lives, and 12,000 were wounded, of whom 1,100 succumbed to those wounds. One of every 26 men who went to sea on merchant ships between 1941 and 1945 perished in the struggle to deliver the goods. William J. Palmer was raised in 1949, towed into Trieste and scrapped. The only things found in the wreck were horse bones and shoes.

Steven Turner graduated from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy in 1961, and served in the U.S. Navy for 30 years. He is a member of American Legion Post 177 in Fairfax, Va. Elmer Cocke is his first cousin.

- Honor & Remembrance