Last survivors of USS Indianapolis and Japanese sub that sank it connect after decades.

On July 29-30, 1945, the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis was traveling to Leyte in the Philippines. Unknown to anyone on board, including the captain, it had just dropped off components of the first atomic bomb on Tinian Island. It was to be assembled there and within a week flown and dropped on its primary target, the city of Hiroshima. Meanwhile, the commander of the Imperial Japanese submarine I-58, Mochitsura Hashimoto, had his eye on his own target: Indianapolis.

Hashimoto released all six of the subs’ torpedoes at two-second intervals to cover the area he knew the ship would be in. Two of those torpedoes found their mark, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s former “ship of state” sank within 12 minutes. Over 300 of the 1,195-member crew were gone with it. One of those men was the ship dentist, Dr. Earl Henry, who had just received pictures of his newborn son, Earl Jr. Many of the survivors ended up in the water with burns, broken bones, trauma and shock, and would not last that long first night with the oil and saltwater magnifying their already excruciating pain.

But for many of the men, the anguish was just beginning. Most people know what happened the second day and beyond from Robert Shaw’s portrayal of the captain in “Jaws.” Sharks attacked the survivors, who tried to huddle in larger groups to discourage them from coming around. But many men started to suffer from delusion, thinking the ship was under them with fresh water and food. They left the group never to be seen again. There were countless cases of heroism from men such as Dr. Lewis Haynes, who did what he could with what meager supplies he had, and Father Thomas Conway, going from group to group trying to encourage and uplift the men, finally succumbing to exhaustion himself. Or Capt. Edward Parke, the Marine commander who saved one hallucinating man after another, preventing them from leaving the group to dive down to the imaginary ship. He, like Conway, died of exhaustion saving his fellow shipmates.

Days later in what one of the planes called a “one in a billion” chance, 316 men were rescued. The rescue ships searched for days before finally realizing there were no more survivors. One of the men who survived the sinking was Jim Belcher, who stayed in the Navy until 1969. In the mid ‘50s he married a woman in Japan, and his oldest son, Jim Jr., was born in Yokosuka in 1957. Another survivor, Harold Bray, remembered thinking, “At first I couldn’t believe it was going down – how could something so beautiful sink?” After the war Bray went on to a career in law enforcement in the town of Benicia, Calif. The captain of Indianapolis, also a survivor, suffered a different fate.

Later in 1945, after the war ended, the Navy initiated court-martial proceedings against Capt. Charles McVay for not “zigzagging.” They even took the unpreceded step of bringing in the commander of I-58. Hashimoto, to his credit, explained to the court that it wouldn’t have made a difference whether it had been zigzagging or not. With the spread of six torpedoes at two-second intervals, it was just a question of which of the torpedoes were going to hit the target.

While the survivors of Indianapolis embraced their captain with open arms, many of the families who lost loved ones in the tragedy did not. While his family tried to shelter him from some of the calls and letters blaming him for the tragedy, they finally took their toll, and in 1968, while sitting in the backyard of his home in Litchfield, Conn., clutching a toy soldier his father had given him in one hand and his service revolver in the other, McVay took his life. It took another 32 years, but thanks to the constant work of the survivors and the work of a middle school student’s project on Indianapolis, he was exonerated. Sen. Bob Smith, R-N.H., who led the charge to reinstate McVay’s good name, had one important ally in convincing Sen. John Warner, R-Va., chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. Warner had received a letter from Commander Hashimoto in which he stated he wanted to join the “brave men who survived the sinking of the Indianapolis … in urging that your national legislature clear their captain’s name … perhaps it is time your peoples forgave Captain McVay for the humiliation of his unjust conviction.” The letter touched Warner, and the resolution exonerating the captain was passed, Hashimoto died 13 days later. His daughter, Sonoe Hashimoto Iida, and granddaughter, Atuko Iida, were invited to the 60th reunion of the survivors and their families in 2005. They were received with open arms and have been a part of the group, which meets every year, since.

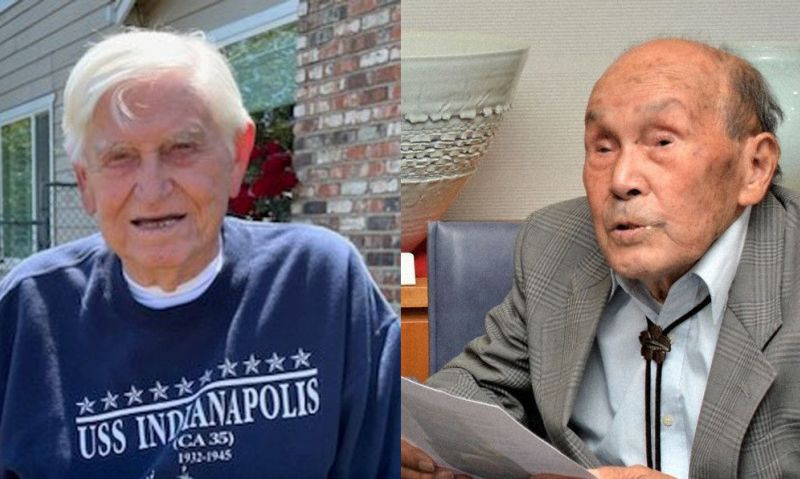

Izumi Harris is a faculty member of the Indianapolis campus of Indiana University. She started attending the July 30 “Honor Watch” originated by Michael Emery, whose uncle William Friend Emery did not survive the sinking. As a member of the Hiroshima Peace Tree Project, she read an article and saw a historic opportunity facing her. Kunshiro Kiyozumi, at 16, was the youngest member of I-58 when it traveled on its fateful mission. He is now 94, living in Masaki, and is the sub’s sole survivor. With the help of Jim Belcher Jr., Izumi traveled to Japan with four letters: one from Belcher, one from Earl Henry Jr., another from Dawn Ott Bollhoefer, whose grandfather Theodore Ott was on Indianapolis, and a letter from the last survivor – 96-year-old Harold Bray. After 78 years, the messages were of reconciliation and peace.

Fri. May 26, 2023 Dear Mr. Kiyozumi, My name is Harold Bray and I am the last survivor of the USS Indianapolis CA-35. I understand that you are the last survivor of your submarine, I-58. I want to extend my hand in friendship to you and to tell you that I bear no ill will towards you or your fellow countrymen. We both fought for our countries and now that the war is over, this is a time for healing. There are no winners in a war. Both sides lose so much-shipmates, families, friends. I off my thanks to your Captain Hashimoto for speaking up for my Captain McVay and saying that his court martial was unjust. Let us look forward to working together to build a better, safer world. Sincerely, Harold J. Bray, S2 USS Indianapolis CA-35

Dear Mr. Harold Bray, Thank you for your kind letter. I was very surprised to read that you were the last survivor of the USS Indianapolis CA-35. I am happy to see you look so young and healthy in the photo. I am now 96 years old. I was 16 years old on July 30, in the I-58 submarine. I was just starting out. Although the war was an unfortunate event, I am moved that we are now living in such a happy and peaceful way, and that we can talk to each other as friends. I will continue making efforts to work for a peaceful world. I would like to send your heart to the spirits of our fallen comrades-in-arms. Thank you very much. Kunshirou Kiyozumi

A final letter from Mr. Kiyozumi to the people of the United States sums it all up 78 years later. “I wish the people of the United States peace, and I hope that you will continue to take good care of your health and work for the good will between Japan and the United States.”

Marty Pay is a university professor, former radio talk show host and small business owner. He has studied the Indianapolis story for the past few years, and is a member of Duby Reid American Legion Post 30 in Sparks, Nev.

- Honor & Remembrance