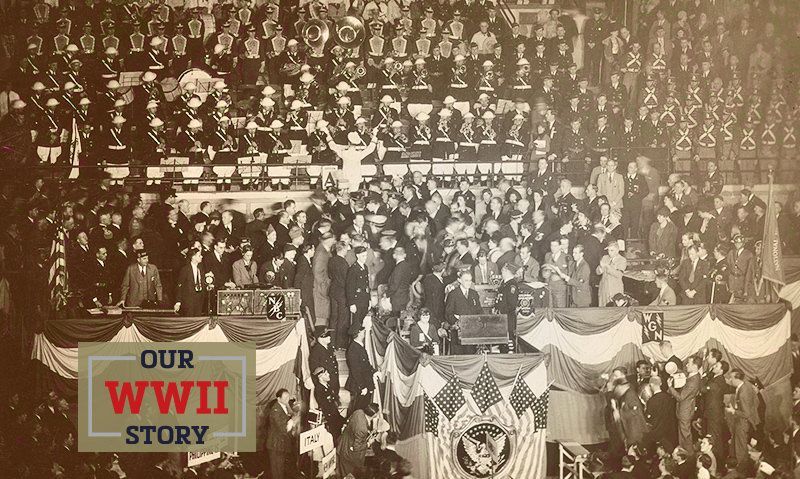

Commander-in-chief’s son accepts the Distinguished Service Medal on behalf of his father.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt did not live long enough to see the end of World War II, nor to receive The American Legion’s most prestigious award for leading the United States and its Allies to victory in it. On Nov. 18, 1945, at the 27th National Convention, in Chicago, Past National Commander Louis Johnson posthumously presented the organization’s Distinguished Service Medal to the 32nd President of the United States. His son, Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., accepted the award for his late father.

FDR had died less than a month before the Allies defeated Nazi Germany in the European Theater and less than four months before victory over Japan in the Pacific.

FDR, who was granted American Legion membership at Lafayette Post 37 in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., based on his World War I tenure as assistant secretary of the Navy and briefly housed a post at his Hyde Park estate, came into conflict with The American Legion from time to time during his presidency, over domestic policies during the Great Depression.

Legionnaires, however, stood by the commander-in-chief during World War II. Roosevelt, who had been a frequent speaker at American Legion national conventions, quickly called on the organization to establish a nationwide training program for World War II air wardens in the event of enemy attack soon after Pearl Harbor. He also called on Legionnaires to help with the draft and to provide emergency services in communities suddenly depleted of trained personnel due to wartime deployments.

“This is not the time nor the place to estimate Franklin D. Roosevelt’s place in history, or to judge the final worth of all the things he has done,” Johnson told delegates at the national convention. “About one thing few of us will differ now: the splendor of his leadership in guiding us into a fellowship with the other free peoples of the world to meet the Fascist threat; and in the creating of the national demand, now so articulate, that this fellowship should not cease to be when the guns were stilled.”

Johnson referenced Roosevelt’s strength to lead though polio had paralyzed his legs since 1921. “I have seen many go apart from the battle, and slip to the rear, from lighter blows than fell on him,” Johnson said. “But he fought on. He compelled death to flee. He refused to even look at the possibility of fear. He came from that hour of darkness with a great compassion, to become the foremost citizen of the world, its inspired leader when its hopes ran low … Somewhere – from great depths – he drew the courage that enabled him to be more than conqueror over a foe that would have beaten many a man. And when all the controversies about him have died, and all the hatreds of the hustings are forgotten, we will tell our children how Franklin Roosevelt fought off death and despair and emerged to be the leader of our darkest hour.”

FDR had been an ardent supporter of The American Legion Endowment Fund and kicked off the New York phase of the nationwide drive to raise $5 million in 1925 to assist disabled veterans and support American Legion service officers. He also – despite doubts it would pass in Congress – enthusiastically signed the American Legion-drafted Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, the GI Bill, famously saying at the time: “With the signing of this bill, a well-rounded program of special veterans' benefits is nearly completed. It gives emphatic notice to the men and women in our armed forces that the American people do not intend to let them down.”

His son, a World War II Navy officer and future member of Congress, told his fellow Legionnaires that the common bond between FDR and veterans was devotion to country. “You men of 1918 and you men of 1945 have one great thing in common with my late father,” Roosevelt Jr. said at the award presentation. “You gave not only of your time and yourself and some with their lives for your country, and I know and you know that my father gave his life for his country … It is that sense of putting your country before yourself, your personal interests, and in fact above life itself, it is that spirit, that tradition, that I feel we veterans have a great responsibility to carry on in America. During the 1920s and the 1930s we saw in Europe country after country slowly disintegrate and end up in anarchy because the people of those countries thought of themselves first and then, if at all, their country. But the thing that has made America great, the reason we have always won our wars, the reason we will never be conquered, is because we Americans put our country first! So I can only say it is our responsibility to carry on that spirit which my father, I feel, so well exemplified.”

- Honor & Remembrance