Author’s father participated in post-Normandy operations.

It’s June. For the last 50 years or so June was the month to remember D-Day – June 6, 1944. The commemoration was celebrated on almost all TV stations with documentaries, firsthand accounts, and of course re-runs of the acclaimed program "Victory At Sea." Tributes ran in newspapers and magazines. Now, like most of World War II, the day is a faded memory, and while the History Channel runs "Pawnshop Wars" or some other non-historical nonsense, some of us remember the sacrifices on the beaches of Normandy – Sword, Gold, Utah, Juno and Omaha, and the landings of the largest armada ever assembled in the history of the world. All to rescue Europe from the grips of tyranny and save the world from a similar fate.

This isn’t a story of another brave U.S. soldier landing on Utah or Omaha, but of another one involved in the follow-up invasion of southern France and a journey up through France and into Germany in the last year of the war. It was called Operation Anvil and was done to secure ports on the Mediterranean and to push the German forces out of southern France.

My father, Tech Sgt. Eugene Yakas, 254th Infantry of the newly formed 63rd Division, arrived later in December 1944. He and his fellow soldiers made their way up the Rhone River valley to the Voges Mountains and into the Alsace region on the Rhine River. There they were met with the second “bulge” – one few people know about, unlike the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium – called the Colmar Pocket.

While the Wehrmacht was attacking through the Ardennes in Belgium, the German Operation Nordwind was intended to push through Colmar and the towns of the Alsace between the foothills of the Voges Mountains and the banks of the Rhine. The plan for Nordwind was to attack the Allies through the Voges and catch the American army in a “Pincer” movement from Belgium in the north, and out of the Voges from the south.

The 254th Infantry was attached to the 3rd Division in this action as Task Force Harris. Some of you may remember Audie Murphy, recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor and later a film star. Murphy was in the 3rd Division and took part in the action of the Colmar Pocket. American divisions were in coordination with the French 1st Army in one of the coldest winters on record, with snow 3 feet deep and temperatures as cold as -20 degrees throughout January and February.

The battle for Jebsheim, a small Alsatian village and a center of German resistance in that sector, saw some of the worst house-to-house fighting of the war, and my father took part in this key battle of the Colmar Pocket. He was awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart in this action, and later the Silver Star when his company was one of the first to break through the Siegfried Line near Saarbrucken, Germany, in March 1945.

Once the Allies pushed the Germans back across the Rhine in March 1945, the 63rd Division made its way across Germany and finally ended their “adventure” as occupation forces in the cities and villages of Bavaria. During his time “keeping the peace” and waiting for his ticket back home to Chicago, dad took the opportunity to record in drawings his impression of the army and the soldiers he had fought against. Some drawings were found in a bound book in which he used the blank pages to record the images. His portrait of his “enemy” shows a great deal of respect for the caliber of soldier he faced many times across the ETO (European Theater of Operation). The models he used for the drawings are a mystery as I found this book after his death, and like most of the soldiers of that war he never chose to speak at length about it or his experiences. I am assuming they were either from memory or from photographs he may have seen. They are compelling images of a formidable foe. [View examples of the elder Yakas’ work on Legiontown here.]

After the war, Gene returned to Chicago to work with his uncle, Stanley Link, a syndicated cartoonist with the Chicago Tribune (owner of the cartoon strips Tiny Tim and Ching Chow). Having not found it his calling, he later went on to architecture school under the GI Bill, and had a long and fruitful career in that profession.

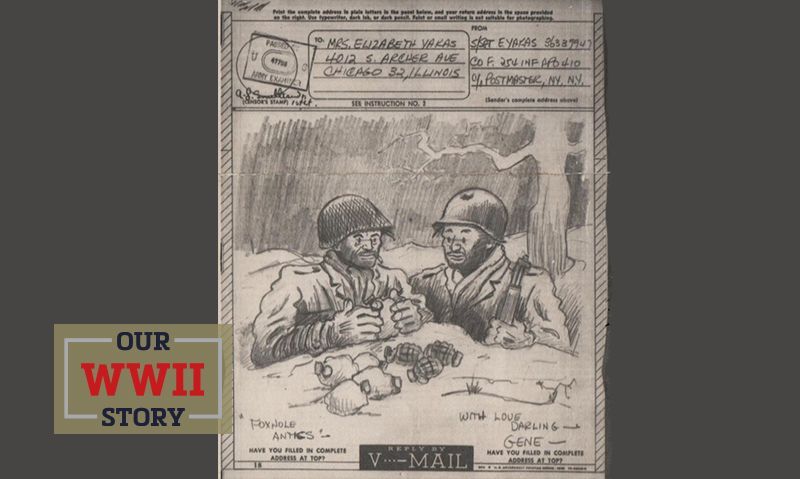

Also, an attempt at humor – using a V-Mail to his wife, my mother – a form of microfiche used in the war to cut the cost of sending letters by GIs. Dad copied the style of a famous WWII cartoonist, Bill Mauldin – of “Willy and Joe” – to make his own cartoon of foxhole GIs camouflaging hand grenades as snowballs. Remember, -20 degrees and 3 feet of snow!

So, I’ve offered you just another way to remember June 6, 1944, and what it meant to the men and boys who fought their way across Europe and into the memories of historians and all the family and friends over the years. We’ve lost many World War II veterans, with not many more remaining. Seventy-seven years from the June 6, 1944, invasion is a long time, but not long enough for us to forget the sacrifices made and the victory won.

- Honor & Remembrance