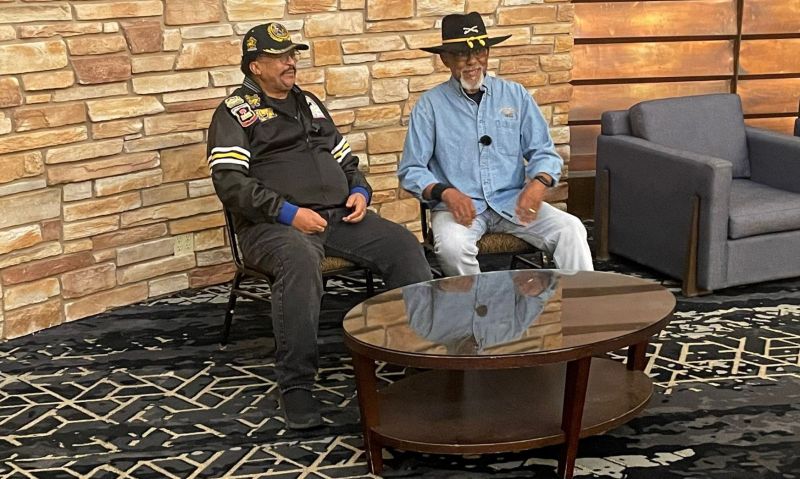

California Legionnaire Ron Jones is in Missoula, Mont., this week to commemorate the 125th anniversary of the Iron Riders’ 1,900-mile trek to St. Louis.

Legionnaire Ron Jones spent 12 years as a nuclear specialist on U.S. Navy submarines during the Vietnam War – the only black engineer on each of the three subs on which he served.

It wasn’t until years later that he realized who was responsible for him getting an opportunity at such a specialty in the U.S. military: men like his father, a World War II veteran and a Buffalo Soldier. Once he figured it out, he started sharing the story of the Buffalo Soldiers – and in particular, their Iron Riders, who bicycled 1,900 miles from Missoula, Mont., to St. Louis, Mo., in 1897.

Jones, a member of American Legion Post 46 in Culver City, Calif., is spending the week in Missoula to take part in the Buffalo Soldiers Iron Riders Gathering to commemorate the 125th anniversary of the ride. A member of the event’s planning committee, Jones has spent decades trying to share the story of the Iron Riders, the Buffalo Soldiers and what they meant to future generations of minority members of the U.S. Armed Forces.

And it all started after his father, one of the founders of the Ninth and Tenth (Horse) Cavalry Association, suffered a heart attack and had to have a quadruple bypass.

“We didn’t have a really great relationship when I was young,” Jones said. “When I went to him see after the bypass, I looked at my father in a different light. He still was really active with the (Calvary Association) … and was like, ‘Look, if you have to go to the meetings I’ll take you.’ In my mind … it was just a lot of old guys who got together and talked about their time in the military. I didn’t give it a lot of thought as to the significance of their service. It didn’t even dawn on me.”

But as he attended the chapter’s meeting and heard the stories, Jones’ perspective changed. “I realized that these guys own a significant role in our country’s history, as far as what Blacks in the military were able to do for our country’s history via their military service,” he said. “I started to realize that if it wasn’t for these men, who showed this country that if you give a Black man some kind of equal opportunity, if you give them the proper training and then stand back and watch what they’re capable of doing … they proved to this country that we as Black people can make a significant contribution to our country via our military service.

“What they ended up doing was showing the country that there was a role for these minorities, and they’re very good at what it is that they do. They are the ones … that showed the country, ‘look at what we’re capable of doing.’ And I realized that … if it wasn’t for the Buffalo Soldiers, who opened the door and showed this country what a minority could do, I would never have been given the opportunity to serve as a nuclear engineer.”

But the road the Buffalo Soldiers paved extends beyond the opportunity Jones was given. “If it wasn't for the Buffalo Soldiers, you wouldn’t have all the other minority regiments that really proved themselves in the military,” he said. “If it wasn’t for the Buffalo Soldiers we wouldn’t have the Tuskegee Airmen or Montfort Point Marines or the Triple Nickels parachute unit or the Harlem Hellfighters or the 761st Tank Battalion. All of these other Black regiments went on to distinguish themselves in the military because of the Buffalo Soldiers.

“But you can look at the next step. If it wasn’t for the Buffalo Soldiers, you wouldn’t have the 442nd Combat Regiment (all Japanese regiment) … (or) the Navajo Code Talkers. They opened the door for all the minorities that came after them.”

As he continued to research the Buffalo Soldiers, Jones came across what he called a “little piece of history that almost no one knew about”: the Iron Riders and their nearly 2,000-mile journey. Since the early 2000s Jones – an avid cyclist who routinely participates in 100-mile rides – has made the Iron Riders the focus of his message.

“This bicycle experiment that was performed is considered the greatest cycling experiment ever undertaken by men in the military,” Jones said. “They weren’t chosen because they were Black. They just happened to be in the right place at the right time. I am so pleased … that here we are now getting press coverage, national coverage … this is great. It’s beyond my expectations where we are today.”

Buffalo Soldiers reenactor Troy Walker, a retired U.S. Marine and vice president of the Greater Los Angeles Chapter of the Ninth and Tenth (Horse) Cavalry Association, came from his home in Temecula to take part in this week’s events.

Walker who earned two Purple Hearts during his three tours in Vietnam, has been a reenactor since 1985. An incident during basic training at Camp LeJeune is what first prompted his interest in the Buffalo Soldiers.

“I rode a horse one day across the road headed into the woods,” Walker recalls. “Some white guys in a truck hollered at me and said, ‘there’s no such thing as black cowboys.’ So I started searching the history … and found out that two of our sergeant majors – Sgt. Maj. (Edgar) Huff and Sgt. Maj. Gilbert Johnson – had been in the Buffalo Soldiers. And when they decided to integrate, they needed instructors to come down and train the black recruits here.

“When I read that history, I said, ‘OK, I want to learn some more about it. And then I learned that when I was in ROTC in high school, some of the gentlemen we knew in the neighborhood had served as Buffalo Soldiers during World War II.”

That led him to joining the association’s Los Angeles chapter, and he’s been learning more about the Buffalo Soldiers’ history ever since. That eventually connected him with Jones and Legionnaire Bobby McDonald, co-chair of the Buffalo Soldiers Iron Riders Gathering planning committee.

The importance of being able to share the story of the Iron Riders for Walker is “the history that we accomplished something,” he said. “Most American movies and history do not tell the story of the Buffalo Soldiers and what the African Americans have actually done. So to find the history out about what these Black men did on bikes, that’s just amazing: to ride that far on a bike across country. It’s a history that needs to be (told). As my grandmother used to say, ‘if you don’t know your history, you don’t know where you’ve been, so you never know where you’re going.’”

- Honor & Remembrance