Texas post has two caravans to Fort Sam Houston in 1952 to quickly get plasma to the troops.

By the Korean War’s second year, the blood shortage for troops fighting overseas reached a crisis level. In the December 1951 American Legion Magazine, writer Eric Northrup summed it up in the words of former Secretary of Defense George C. Marshall, who in one of his last acts in that office “went on the national airwaves and told the American people that the reserve supply of blood plasma for Korea was exhausted. Not low. Not below quota. Exhausted.”

Blood donations stood at nearly one-tenth the need, Marshall said. Most of the blood at the time was coming from active-duty personnel, but much more was needed. The American Legion was pushing for deposits at blood banks, as it had vigorously done since 1942 in World War II, when the organization’s blood donor program was launched.

Legionnaire Edna Tarver of Post 669 in Laredo, Texas, was enraged that public donations were running so low at a time of war. She learned that one of the problems was getting mobile collection units to community sites, such as Legion posts. The Red Cross needed to expand capacity and facilities to meet the need and was having difficulty keeping up.

Tarver wrote authorities and later learned from the 4th Army headquarters that “its Fort Sam Houston blood center (at San Antonio, 150 miles away) could accommodate visitors and send blood winging to Korea, same day.”

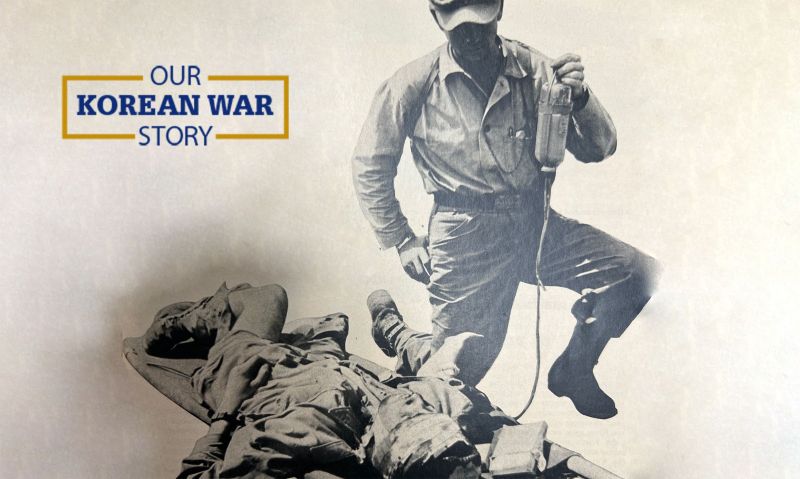

Post 669, led by Tarver, launched a blood caravan at 5 a.m. on March 11, 1952, filling four buses and multiple private vehicles with willing donors.

“The sun was still climbing when busy corpsmen at Ft. Sam Houston began tapping their biggest (37 gallons) haul,” The American Legion Magazine later reported. “The 300-mile round trip of 350 donors was the national community blood story of the year.”

Post 669 coordinated another caravan in September that year, sending 210 more donors to San Antonio and just over 26 more gallons of blood to Korea.

The 1951 magazine made the point that blood collections typically dry up when the United States is not in an emergency. The Korean War, Northrup wrote, was a serious emergency, and the troops were paying for apathy by donors between the wars. Much more effective, Northrup wrote, is to plan and save blood in a bank before a crisis arises.

“It is very easy to work out, on paper, a national voluntary blood insurance program, that would solve forever all national and local blood needs,” Northrup wrote. “But how you would get everybody to give the few pints in a lifetime in a systematic way that would make national blood insurance work is a question with no realistic answer today.

“First step would be to destroy the idea of waiting for an emergency. That is definitely out, right now. Right now, there's a terrific emergency that cannot wait and must be met by the old system. You phone or visit your Red Cross unit to arrange a date for a donation for the Armed Forces. Doctors advise that five pints a year is the safe limit for giving.”

- Honor & Remembrance