VP, Secretary of State share their observations, concerns for the future after the armistice.

The Korean Armistice Agreement was signed July 27, 1953, to “ensure a complete cessation of hostilities … until a final peaceful settlement is achieved.” That settlement awaits to this day.

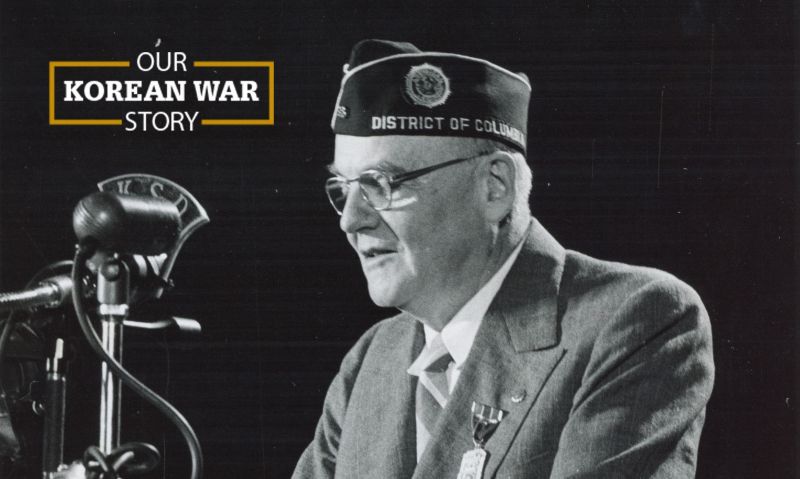

A little over a month after the cease-fire was called and the line of demarcation separating South Korea and North Korea was set, Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles delivered detailed remarks in St. Louis to the 35th National Convention of The American Legion. The newly halted Korean War was a main subject for both speakers, both of whom were members of The American Legion.

Nixon, who would later become the 37th U.S. president, told Legionnaires “we can be thankful today that the shooting in Korea has been stopped and has been brought to an end.”

However, he firmly defended the decision of the Truman administration to enter the fighting there. “The decision to go into Korea was right. It was right because the communists had to be stopped. And let me say that in the past I have had occasion to disagree with the former President of the United States, Mr. Truman, on some issues, but on this issue, President Truman was right, and he deserves credit for making that decision, and I’m glad to say it in his own home state.”

In honor of all who fought, died and were wounded in the Korean War, he said all Legionnaires have an obligation “to see that the principles for which they fought are not compromised in the negotiations for the peace which follow the war.”

Nixon and Dulles both spoke of America’s perceived lack of military readiness and defense investment as opportunities for communist forces to act. “They began a war in Korea because they thought they could get away with it,” Nixon told the crowd. “They don’t begin wars when they think they can’t get away with it … military weakness leads to attack. Weakness, either in arms or in statement of intention, will invite attack by the communist leaders, and therefore it is very simple to reach the conclusion that the first plank in the policy for America which can and will lead to peace must be one which will assure that America maintains its military strength.”

“The Korean War began in a way in which wars often begin – a potential aggressor miscalculated,” Dulles said in a speech the following day. “From that, we learn a lesson which we expect to apply in the interests of future peace. The lesson is this: if events are likely which will in fact lead us to fight, let us make clear our intention in advance; then we shall probably not have to fight. Big wars usually come about by mistake, not by design. Aggressive despots think that they can make a grab unopposed, or opposed, but feebly. So, they grab. And to their surprise they find themselves involved in unexpected opposition which means major war. Many believe that neither the First World War nor the Second World War would have occurred if the aggressor had known what the United States would do.”

Military preparedness – and making sure the rest of the world knows it – can prevent major war, Dulles said. “The communists thought, and had reason to think, that they would not be opposed except by the then-small and ill-equipped forces of the Republic of Korea. They did not expect what actually happened. There is, in this, a profound lesson. All the peoples of the world passionately want peace. But too often they think that peace is won merely by pacifism. They should know by now that peace is not had merely by wanting it, or talking about it, or seeming to accept the role of a door mat. To win peace is as hard, if not harder, than to win a war. To achieve peace is a science.”

Some at the convention had expressed concerns about the Eisenhower administration’s plans to cut back spending on air power, rather than foreign aid and U.S. military investment overseas. Nixon explained the thinking this way: “You cannot separate sound national security from a sound national economy.”

He further added that of the $100 billion in defense spending planned, $60 billion would go toward air power and that “by Dec. 31, 1955, more combat planes will be delivered than the previous administration had planned for that date. Now, that doesn’t look like any cut to me in combat strength. And finally, this will be accomplished with less money by eliminating waste and duplication and personnel.”

He said the drawback in federal defense spending at the time was essential to prevent an economic collapse in the United States. “Had we continued the budget plans and the budget estimates which we inherited from the previous administration, we would have added $44 billion to the national debt from 1952 to 1956 – $44 billion. What would that have meant? This is what it would have meant: it would have meant higher taxes, higher prices, a continuation of government controls, and more government controls … if continued inevitably in the future, such a policy would have meant nothing more or less than national disaster through national bankruptcy. We had to make a change. We had to get balance into the program, and we had to get it while at the same time maintaining our defense, and we think that is what we have done.”

He explained that U.S. investment in security outside the country amounted to about 10 cents on the defense dollar “for technical assistance to nations abroad, to shore up their economies so that they will be better able to defend themselves … Much as we would like to, if we would, the United States, with its people – strong as we are, with our great productive capacity, great as it is – simply cannot stand alone. We need allies. We need bases, and we are either all going to fall together, or we are going to stand together. And, under the circumstances, I believe that the money that has been appropriated by the Congress and approved by this administration for foreign aid has been in the best interests of the United States, and on that basis can be approved by the American people.”

Dulles told the crowd that the Korean War, despite a lack of foresight on both sides, proved to the world that “aggressors, hostile to the free world, cannot go on enlarging themselves by the conquest of small nations, until they become bloated with power and dizzy with success.”

That U.S. and U.N. forces were able to drive the enemy back across the 38th Parallel turned the attempted conquest into a zero gain for the enemy, he added. “The aggressor, which initially overran all of Korea except a small beachhead at Pusan, has been thrown back to, and beyond, his point of beginning. He now controls 1,500 fewer square miles than when he started and has incurred casualties totaling about 2 million. The cost to the aggressor has been colossal. His gains have been nil. Some persons seem to feel that our men who fought in Korea fought uselessly. That is a cruel misjudgment of the situation.”

Dulles commended U.S. military personnel who not only saved the peninsula from complete conquest but also prevented further expansion. “They showed a discipline, a courage, a competency, on the land, in the air, and on the sea, which has gained the respect of the whole world, including our enemies. Because of what they did, we today live more safely. Our armed services wrote in Korea another epic chapter of glorious service for the nation. For that, the American people must be forever grateful.”

His speech also touched on amnesty for prisoners who deserted communist units, as well as a proposed treaty to establish a 16-nation security alliance along the Pacific in Asia and how the U.N. must listen to South Koreans in setting security policy there. “The United Nations has been inclined to debate Korean matters without paying much attention to the Republic of Korea,” Dulles told the convention delegates. “Some of the member states seem to have assumed that the Republic of Korea would automatically go along with anything that the United Nations wanted. In fact, the Republic of Korea is not a puppet. It has a will of its own, and 20 million people have backed that will with enormous sacrifices. The Korean question cannot be settled without the Republic of Korea.”

Dulles was uncertain how negotiations for a lasting peace would turn out, but he did say, “The United States, at least, has no secret or ulterior purposes. We seek no pretext for turning Korea into a United States base on the Asia mainland. We seek only the long-proclaimed goal of the United Nations, namely, the peaceful unification of Korea under a representative form of government. We stand for ‘a united Korea for free Koreans.’”

Ominously, he warned the Legionnaires that the situation on the Korean peninsula could not be interpreted as “an isolated affair… The Korean War forms one part of the worldwide effort of communism to conquer freedom.”

In particular, he raised attention about the ongoing French-Indochina War, then eight years in, and how the armistice could not serve as an opportunity for communist interests to simply shift more forcefully to Southeast Asia. “The outcome affects our own vital interests in the Western Pacific, and we are already contributing largely in material and money to the combined efforts of the French and of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.”

The Korean War, and the ongoing and fighting in Southeast Asia and how the United States might act, left Dulles to observe America’s complicated and evolving place on the world stage in the mid-1950s. “There is much talk these days about the increased responsibility that now devolves upon the United States. That responsibility is a reality. We need not, however, shrink from it out of fear that it will involve the scrapping of our American traditions and ideals. We do not now have to be constantly taking international public opinion polls to find out what others want and then doing what it seems will make us popular. Leadership won in that way is shabby and fleeting. Our present duty is rather to adhere with increased loyalty to what, in our past, has been tested and found worthy. For more than a century, our conduct and example won for us worldwide respect and prestige. That is the only kind of leadership worth having. I hope that we shall continue to win respect and prestige in the way our forefathers won it. That is the American way. It is the way we expect to follow.”

- Honor & Remembrance