U.S. foreign policy from the 19th century should provide guidance on dealing with China's move into Latin America.

Much has been reported about Washington’s pivot into Asia and the Pacific. What’s not as well-known is Beijing’s pivot into the Americas. Like a global chess match, Beijing is probing the Western Hemisphere and sending a message that it, too, can cultivate trade and military ties outside its neighborhood. Given that the United States has been the predominant power in this hemisphere since the 1800s, China’s message warrants a response.

Before recapping some of China’s moves in Latin America, it’s important to note that there are pluses and minuses to Beijing’s increased interest and investment in this hemisphere. Investment from China, Europe, Britain and the United States is fueling a much-needed development boom in South America. That’s a plus. But China’s riches come with strings, and that’s what raises concerns.

Driven by a thirst for oil and other resources, China is aggressively and strategically building its economic portfolio in the Western Hemisphere. A study in Joint Forces Quarterly (JFQ) offers the highlights:

- $1.24 billion to upgrade Costa Rica’s main oil refinery;

- $28 billion to underwrite oil exploration and development in Venezuela;

- $2.7 billion, including a new hydroelectric plant, for access to Ecuadoran oil;

- $10 billion to modernize Argentina’s rail system and $3.1 billion to purchase Argentina’s petroleum company outright;

- $1.9 billion for development of Chile’s iron mines;

- a planned “dry canal” to link Colombia’s Pacific and Atlantic coasts by rail, with dedicated ports at the Pacific terminus for shipping Colombian coal to China;

- $3.1 billion for a slice of Brazil’s vast offshore oil fields.

Brazil is a prime example of how Beijing is using its checkbook to gain access to energy resources. As The Washington Times reports, China’s state-run oil and banking giants have inked technology-transfer, chemical, energy and real-estate deals with Brazil. Plus, China came to the rescue of Brazil’s main oil company when it sought financing for its massive drilling plans, pouring $10 billion into the project.

“They are buying loyalty,” warns a former British diplomat to the region. Indeed, U.S. diplomatic cables reveal concerns that Beijing’s largesse is making the Bahamas, to cite just one example, “indebted to Chinese interests” and establishing “a relationship of patronage…less than 190 miles from the United States.”

That brings us to the security dimensions of the China challenge. We know from our own history that trade and economic ties often lead to security and defense ties. And that’s exactly what’s happening as China lays down roots in the Americas:

Officials with U.S. Southern Command reported in 2006 that Beijing had “approached every country in our area of responsibility” and provided military exchanges, aid or training to Ecuador, Jamaica, Bolivia, Cuba, Chile and Venezuela.

- The Argentine defense minister traveled to Beijing in 2012 to hail a “bilateral strategic association in defense cooperation with China.”

- JFQ reports that most Latin American nations “send officers to professional military education courses in the PRC.”

- A congressional commission reports that Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador are buying Chinese arms. Bolivia has a military cooperation agreement with Beijing.

- According to a 2012 Pentagon study, Beijing has sent senior military officials to Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Brazil, Mexico and Argentina in the past five years.

- A report in Military Review, a journal of the U.S. Army, concludes that China is “winning a foothold” in the Americas, detailing the flow of Chinese small-arms, medium artillery, air defenses and ground-attack aircraft into Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela.

- The JFQ report concludes that Chinese defense firms “are likely to leverage their experience and a growing track record for their goods to expand their market share in the region, with the secondary consequence being that those purchasers will become more reliant on the associated Chinese logistics, maintenance and training infrastructure.”

In short, China’s moves represent a challenge to U.S. primacy in the region—a challenge that must be answered. But how?

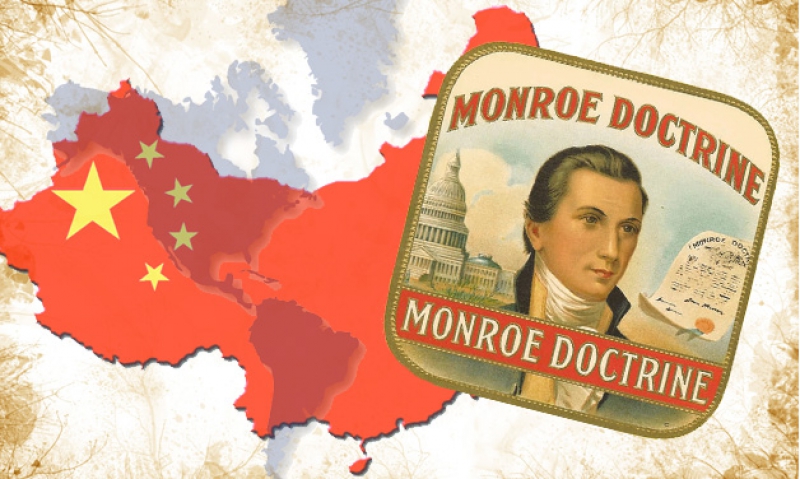

A good place to start would be to dust off the Monroe Doctrine. The origin of the threats may change—France and Spain in the 1800s, Imperial Germany in the early 1900s, the Soviet Union during the Cold War—but the Monroe Doctrine remains an important guide for U.S. foreign policy.

“Monroe 2.0” should make it clear to Beijing that while the United States welcomes China’s efforts to conduct trade in the Americas, the American people look unfavorably upon the sale of Chinese arms in this hemisphere and would not countenance the basing of Chinese military personnel or export of China’s authoritarian-capitalism model into this hemisphere. To borrow the polite but candid language of the original Monroe Doctrine, a Chinese outpost in the Americas could only be seen as an “unfriendly” action “endangering our peace and happiness.”

Likewise, Washington needs to send the right message—and in the right way—to the Caribbean, Central America and South America. Specifically, Washington should emphasize that just as they are not U.S. colonies or European colonies, they should not allow themselves to become Chinese colonies. Already, there is a backlash in Brazil and Argentina against China buying up land, and in the Bahamas against the influx of Chinese workers. Washington should leverage this backlash.

U.S. actions should amplify U.S. pronouncements:

- The United States should make hemispheric trade a priority, instead of allowing trade deals to languish. Colombia and Panama waited five years for the U.S. to approve free-trade agreements.

- The United States should revive aid and investment in the Americas, instead of allowing China to outflank it. It pays to recall that Washington used to conduct the sort of checkbook diplomacy that characterizes Beijing’s approach to Latin America.

- Washington should be proactive on hemispheric security, building on successful partnership-oriented models in Colombia and Mexico. China will fill the vacuum created by a distracted United States.

Monroe 2.0 would avoid conflict by helping Beijing understand how serious the United States is about the Americas. What was true in the 19th and 20th centuries must remain true in the 21st: There is room for only one great power in the Western Hemisphere.

- Landing Zone