Around the world, fallen heroes are not forgotten this Memorial Day.

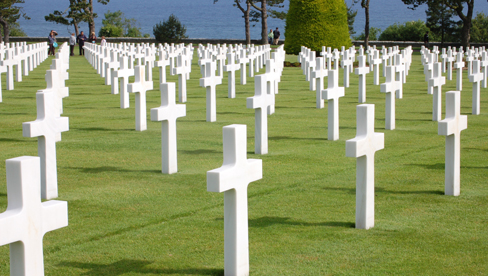

Above Omaha Beach sits the Normandy American Cemetery, where many of those who fought their way ashore in World War II now rest. Normandy is one of 24 overseas U.S. military cemeteries, and 25 memorials, monuments and markers, maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission. They all share the same purpose: to honor the fallen by commemorating the service, achievements and sacrifice of our nation’s armed forces – our war dead, missing in action, and those who fought at their sides. This mission is as old as antiquity. In his history of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides quotes Pericles in the funeral oration the Greek hero delivered after the first battles of the war: “For heroes have the whole earth as their tomb; and in lands far from their own, where the column with its epitaph declares it, there is enshrined in every breast a record unwritten with no tablet to preserve it, except that of the heart.” Recognizing the need for a federal agency to be responsible for honoring U.S. armed forces where they had served, Congress created the ABMC in 1923. President Warren G. Harding appointed as its first chairman General of the Armies John “Black Jack” Pershing, who led the American Expeditionary Force to victory in World War I. For 25 years, until his death in 1948, Pershing made the ABMC his life’s work. He eloquently defined the commission’s purpose when he promised that the U.S. government would perpetuate the memory of the bravery and sacrifice of our men and women in uniform. “Time,” he wrote, “will not dim the glory of their deeds.”The overseas cemeteries serve as resting places for 124,917 U.S. war dead: 30,921 from World War I, 93,246 from World War II, and 750 from the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). Another 94,135 U.S. servicemen and women who are missing in action, or were lost or buried at sea during the world wars and the Korean and Vietnam wars, are commemorated by name on Tablets of the Missing. Many of the dead are buried in cemeteries located on or near the battle-scarred fields they died liberating. In all cases, host countries provide the cemetery lands to the United States in perpetuity, free of charge or taxation.They range in size from Flanders Field in Belgium, where 386 Americans who died in the closing weeks of World War I are buried, to the Manila American Cemetery, where 17,202 U.S. military and Filipino nationals who fought and died in the vast theater of the Pacific during World War II rest.The ABMC’s Web site, www.abmc.gov, has descriptions of, and directions to, each cemetery, where landscaped graves and headstones of pristine white marble are meticulously maintained. The buildings are enriched with classical architecture and works of art. While beautiful objects in and of themselves, many of these also depict the operational campaigns and troop movements associated with those memorialized at each site. Cambridge American Cemetery sits on land, donated by the University of Cambridge, which served during World War II as a natural landing field for Allied bombers and fighters based in England. Its memorial, made of Portland stone, houses a small nondenominational chapel and a large map room. The outstanding feature of the room is its impressive map, 30 feet long and 18 feet high, which shows the principal sea routes across the Atlantic and the types of naval and commercial craft that transported U.S. troops and supplies to Europe. The mosaic ceiling is a memorial to those who lost their lives while serving in the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, whose missions were so dangerous that their life span at the beginning of the war was measured in days. The ceiling depicts ghostly aircraft, accompanied by angels, making their final flight toward the altar.The ABMC’s responsibility goes beyond maintaining beautiful and inspirational sites. It has an equally important duty to perpetuate the stories of courage and sacrifice that those honored can no longer tell themselves.The poet Archibald MacLeish’s younger brother Kenneth died in World War I, when his plane was shot down over Belgium by a German fighter. In his poem “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak,” MacLeish calls on the living to remember those who died in war and give significance to their lives: “They say, We leave you our deaths: Give them their meaning.” Kenneth MacLeish is buried in Plot B at Flanders Field American Cemetery. Kenneth defined himself at Yale when he made the decision to join the university’s flying club, a group of privileged young Americans who had the foresight and skill to prepare themselves for their nation’s call to war. Called “the Millionaires’ Unit,” the highly trained Yale Aero Club became the Navy’s first air reserve squadron, fighting for freedom in the skies of Europe during World War I. Kenneth was killed in a dogfight with German Fokker planes less than a month before the armistice, and died a true pioneer of U.S. naval aviation. Brookwood American Cemetery is the only U.S. military cemetery of World War I in the British Isles. The names of 563 American soldiers and sailors, who have no graves except the sea, are inscribed on the walls of the chapel. Buried at the Oise-Aisne cemetery is the poet Joyce Kilmer, who wrote the famous poem “Trees.” As a family man with wife and children, Kilmer was not required to serve. Nevertheless, he enlisted and, once in France, had no intention of being kept out of action. On July 30, 1918, a sniper’s bullet ended his life at 31.More U.S. military personnel lie at rest at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery than at any other U.S. cemetery in all of Europe. Many were killed in the bloody Meuse-Argonne Offensive in the fall of 1918, a campaign that remains the largest U.S. military offensive ever. Of the 119 Medals of Honor awarded for World War I, nine of the recipients are interred at Meuse-Argonne. Inscribed on the Tablets of the Missing at Cambridge American Cemetery is the name of Joseph P. Kennedy Jr., a Navy lieutenant and the older brother of President John F. Kennedy. Despite the fact that Kennedy had completed 25 combat missions and was eligible to return home, he volunteered to be part of a high-risk bombing mission. On Aug. 12, 1944, the explosives aboard Kennedy’s plane detonated prematurely and destroyed his aircraft over Suffolk.Also commemorated at Cambridge is Maj. Glenn Miller, who volunteered for the Navy at the peak of his career as a bandleader. After being told by the Navy that it did not need his services, Miller persuaded the Army to accept him so he could, in his own words, “be placed in charge of a modernized Army band.” On Dec. 15, 1944, Miller was to fly from the United Kingdom to Paris to play for the soldiers who had recently liberated the city. His single-engine plane disappeared over the English Channel in bad weather. Thirty-eight miles south of Rome sits the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery, the final resting place of 7,861 Americans who lost their lives liberating Italy in World War II. Commemorated on the Wall of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery are the five Sullivan brothers, who were lost at sea when their ship was sunk by a Japanese submarine during the Battle of Guadalcanal. Also memorialized at Manila are the two crewmen killed aboard John F. Kennedy’s PT-109 in the Solomons when it was rammed by a Japanese destroyer. Twenty-eight Medal of Honor recipients are commemorated at Manila American Cemetery. One was Pfc. George Benjamin, who was a radio operator in the Leyte land campaign. Benjamin was advancing in the rear of his company as it engaged a well-defended Japanese stronghold. His Medal of Honor citation states that when a rifle platoon supporting a light tank hesitated in its advance, “he voluntarily and with utter disregard for personal safety left his comparatively secure position and ran across bullet-whipped terrain to the tank, waving and shouting to the men of his platoon to follow. Carrying his bulky radio and armed only with a pistol, he fearlessly penetrated intense machine-gun and rifle fire to the enemy position, where he killed one of the enemy in a foxhole and moved on to annihilate the crew of a light machine gun ... he continued to spearhead the assault, killing two more of the enemy and exhorting the other men to advance, until he fell mortally wounded.” Those honored in overseas cemeteries, young, many known but to God, all gave their lives for the cause of freedom. As Archibald MacLeish so movingly said, they leave us their deaths. The survivors have a responsibility to tell their stories to future generations, and the American Battle Monuments Commission is committed to that mission. Max Cleland is secretary of the American Battle Monuments Commission. He served as administrator of the Veterans Administration under President Jimmy Carter and is a former U.S. senator from Georgia.

- Magazine