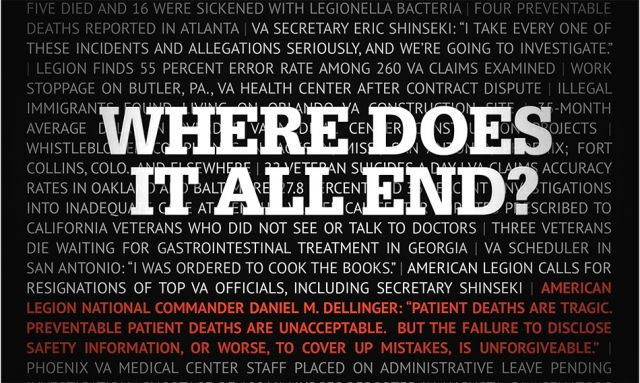

Preventable deaths, falsified records, billion-dollar cost overruns, a burgeoning claims backlog and bonuses for those responsible lead The American Legion to its tipping point.

Forget, for a moment, the secret list blamed for the deaths of up to 40 veterans who waited months to see VA doctors in Phoenix. Forget the CNN report in late April that turned an interview with a retired VA doctor, a whistle-blower, into a media firestorm that led The American Legion to call for the resignations of VA Secretary Eric Shinseki and his undersecretaries for health care and benefits, weeks before Shinseki finally stepped down May 30. Forget other VA whistle-blowers around the country who followed Drs. Sam Foote and Katherine Mitchell in Phoenix by telling investigators and the media they were instructed to hide the truth about long-delayed doctor appointments.

The problem runs deeper than Phoenix. It runs deeper than VA’s inability to keep up with growing and changing patient needs.

The bigger problem is accountability, “a culture shift that needs to be made,” according to Rep. Jeff Miller, R-Fla., chairman of the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs.

The string of accusations, investigations and congressional hearings into VA’s problems confirms this is not an isolated problem. “This is national,” says Mitchell, one of the longtime Phoenix VA physicians who raised concerns. “There are significant patient-care and patient-safety issues everywhere.”

Issues include preventable deaths of veterans, caused by infections and a lack of timely care; lost, delayed and denied disability claims; cost overruns on overdue hospital construction projects that top $1.5 billion; evidence of wrongdoing destroyed; performance bonuses for VA executives in charge of failing facilities; and an inability to keep up with the needs of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans coming home with PTSD, traumatic brain injuries or other psychological and neurological conditions.

In Augusta, Ga., at least 4,580 gastrointestinal consults were delayed for VA patients. Delayed colorectal examinations were blamed for the deaths of at least six veterans in Columbia, S.C., and as many as 23 nationwide. In Pittsburgh, meanwhile, a VA regional administrator received a bonus after a Legionella outbreak was blamed for six veteran deaths at a medical center he supervised. And for nearly 18 years, the Dayton, Ohio, VA potentially exposed hundreds of dental patients to hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

All of these issues arose before Foote stepped forward in Phoenix to allege that another 40 veterans died waiting for care, a problem obscured by duplicitous bookkeeping that made it appear that the facility in Arizona’s largest city was keeping good on the agency’s promise to see patients within 14 days while actually keeping them waiting for months. Phoenix, however, finally fixed national attention on VA and its bigger systemic problem: accountability. Just three employees were placed on administrative leave after the Phoenix story was aired, and the VA inspector general went to Arizona to investigate.

As more stories of falsified appointment documentation, secret lists and cover-ups emerged nationwide, veterans wanted action. And when the VA inspector general reported that Phoenix-like patient waiting times and falsified data were systemic across the agency, it became impossible for Shinseki to keep his job.

“It is not the solution, but it is a beginning,” American Legion National Commander Dan Dellinger said. “Too many veterans have waited far too long to receive the benefits that they have earned. Wait times are increasing even for fully developed claims. But it was never just about a few of the top leaders. The solution is to weed out the incompetence and corruption within the VHA and the VBA so the dedicated employees can continue to perform admirably on behalf of our nation’s veterans.”

The lingering pessimism among veterans who regularly deal with VA is understandable.

The disability claims backlog has exploded in the Philadelphia, Phoenix, Columbia, S.C., Oakland, Calif., Baltimore and Waco, Texas, regional offices, to name a few. Claims decisions are so inconsistent that one Vietnam War Navy veteran’s Agent Orange cancer claim was approved by the Wichita regional office, while a fellow sailor with the exact same cancer who served on the exact same ship in the exact same waters at the exact same time saw his claim denied in Denver. Whether it’s a soldier looking for relief through a PTSD claim or a spouse applying for help because she provides 24/7 care for her husband whose body was shattered by a roadside bomb in Iraq, it can be a game of regional office roulette, where a veteran’s chances of a fair and timely claims decision may be more about geography than about the facts.

In Los Angeles, meanwhile, homeless veterans sleep on Skid Row sidewalks while students at one of the most exclusive schools in the country play sports on land donated specifically to permanently house former servicemembers. A federal judge has ordered the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center to terminate this and other illegal leases; instead of complying, VA has appealed in a city known as the homeless veteran capital of the world.

For a real test of veteran patience, one need only look to Denver, Orlando, Las Vegas and New Orleans, where construction projects for new medical centers are years past due and average $366 million over budget per hospital. It’s not yet clear if a new Denver VA medical center will ever be completed, a decade after VA walked away from an offer of free land for a new hospital at the former Fitzsimons Army Medical Center.

Veterans have been frustrated to the point of anger in dozens of communities throughout the nation where care or benefits decisions have been delayed or effectively denied. Meanwhile, millions of dollars in performance bonuses have been paid to executives and staff who are often directly responsible for the problems.

VA construction chief Glenn Haggstrom collected nearly $55,000 in bonus money despite delays and cost overruns at hospitals under construction. Diana Rubens, who oversees VA’s disability benefits claims offices, received almost $60,000 in bonuses even though the backlog increased nearly sevenfold on her watch. A $63,000 award was presented to VA regional director Michael Moreland, who oversaw the VA medical center in Pittsburgh before retiring in the aftermath of the deadly Legionella outbreak. New York VA official David West, who oversaw the chronic misuse of insulin pens that exposed hundreds of veterans to blood-borne illnesses, received $26,000 in bonus money.

From fiscal 2007 to 2011, VA paid senior executives about $3 million a year in bonuses.

Beyond dollars, the accountability issue extends to VA officials with questionable track records who are reassigned or rehired at another VA facility rather than removed. VA financial manager Jed Fillingim reportedly resigned after a fellow employee fell out of a government pickup he was driving and died. The incident allegedly took place while the two were attending a conference near Dallas in June 2010. Both Fillingim and the colleague had been drinking at the time, according to news reports.

Fillingim resigned from the Jackson, Miss., VA after the incident and was rehired in March 2011. He has since taken a VA management position in Augusta, Ga., where his annual salary tops $100,000, news reports say.

Whistle-blowers, despite protections in federal law, fear the consequences of their actions.

“There is corruption and retaliation throughout the (VA) medical centers – not just in one or two places,” Mitchell says. The American Federation of Government Employees, the largest union of federal employees, has called on VA to protect whistle-blowers who reveal controversial problems and to end “a culture of fear that has plagued the agency and negatively impacted veterans’ care.”

Physicians at other VA medical centers have contacted Mitchell with their own stories since she stepped forward in late April, she says. She isn’t naming names. But Foote, who recently retired from the Phoenix VA, has echoed Mitchell’s charges of retaliation against those who have raised concerns about patient care.

In early May, Dr. Jose Mathews told ABC News and the Center for Investigative Reporting that he lost his position as chief of psychiatry at the St. Louis VA Medical Center after telling his bosses that some psychiatrists were only seeing patients for three hours a day. Mathews filed a whistle-blower complaint with allegations of two preventable veteran deaths.

VA’s oversight process is also in question. Miller has called attention to “management failures, deception and a lack of accountability permeating VA’s health-care system” in a letter to the White House. That came after a VA inspector general’s investigation concluded that a lack of leadership and oversight at the Atlanta VA contributed to the deaths of three patients. Upon visiting the facility, “we learned that no one was fired or otherwise held accountable for the hospital’s failure linked to the death of these veteran patients,” Miller wrote. “The complacency and deceitfulness of VA leadership at both the local and central office levels cannot be tolerated when the health and safety of our veterans and their families are at stake.”

More recently, the VA Office of Medical Inspector concluded that agency employees in Cheyenne, Wyo., and Fort Collins, Colo., were taught how to manipulate records to hide long delays in treating patients last year. No one was disciplined. The matter resurfaced in the spring when USA Today obtained an email from a VA employee with instructions on altering agency records. The alleged author was immediately placed on administrative leave – suggesting that embarrassing publicity, not breaking the rules, was the last straw.

Against this backdrop, The American Legion re-evaluated its vigorous support for Shinseki’s leadership and asked him, with all due respect for his military career, to step down. “A career soldier and Vietnam War veteran, Gen. Eric Shinseki has served his country well,” Dellinger said in a press conference on May 5. “His patriotism and sacrifice for this nation are above reproach. His record as the head of the Department of Veterans Affairs, however, tells a story of bureaucratic incompetence and failed leadership.”

VA Undersecretary for Health Robert Petzel maintained in April that the agency had found nothing amiss in Phoenix, seven months after Mitchell first filed a complaint with the Office of Inspector General. When it became clear that VA couldn’t defend that position, the hospital director and two other officials were placed on administrative leave. “VA clearly has a widespread problem that goes beyond the misbehavior of three people,” Dellinger observed.

Verified by investigations or not, it’s a problem that has been reported from Phoenix to San Antonio, El Paso to San Francisco, Buffalo to Waco, Orlando to Fayetteville, Chicago to San Juan. The problem appeared to have been missed by the secretary, whose first public response to calls for his resignation was a vow to simply communicate better with veterans service organizations.

The barrage of disclosures about performance and accountability problems made April and May some of the most embarrassing months in VA’s history. But these problems did not come out of nowhere and are by no means new.

Days after the 2008 election, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a list of “urgent issues” facing the new president and Congress. At the top of the list: caring for veterans.

“We have identified a number of weaknesses with the health care returning servicemembers are receiving as well as the complex and cumbersome disability systems they must navigate,” GAO reported. Fixing the problems “will require sustained attention, systematic oversight by DoD and VA, and sufficient resources.” Additional reports have surfaced showing that VA was made aware of appointment scheduling problems.

Six years later, many of the same problems persist, complicated by new allegations of falsified reports and fears of retribution against those who tell about them. That was the tipping point for The American Legion. As audits and investigations continued in May – amid growing accusations, fading trust and the resignations of Shinseki and Petzel – VA’s focus was more on defending itself than advancing its main purpose. “If you have a problem, identify it and then solve it,” says Mitchell, one of the Phoenix whistle-blowers. “Don’t cover it up. It doesn’t make it go away.”

Ken Olsen is a frequent contributor to The American Legion Magazine.

- Magazine