A historic American Legion meeting hall gave World War I veterans a home and an Oklahoma town a legacy.

It was born in a time so desperate that local boys unloaded trucks for day-old bread and a third of Oklahoma families depended on federal relief for the most basic food and clothing. Its variegated sandstone walls were raised by drought-busted farmers lucky to qualify for $23 a month in Works Progress Administration wages, and paid for in part with money raised at a barbecue, a bridge tournament and a benefit football game.

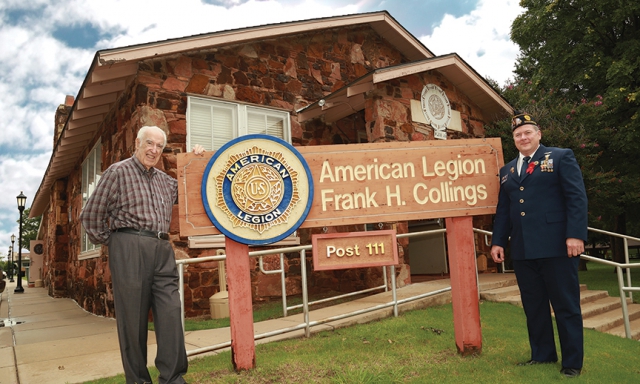

The American Legion meeting hall of Frank H. Collings Post 111 in Edmond, Okla., feels like a place where, if you listen in the hallowed quiet of a steamy July afternoon, you might hear the voices of veterans of the Great War, pillars of the business community and professors at Central State Teachers College.

“This is like being in Independence Hall or visiting a historic Civil War battlefield,” says Post 111 Commander Rob Willis, who intends to write the biography of this place as a tribute to the founders, the building’s namesake and nearly a century of service to central Oklahoma veterans. “It gives me goose bumps.”

The post is named for the first resident of Edmond killed in combat in World War I. Cpl. Frank Collings died July 1, 1918, at 23 and is buried at the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery in France. Three of Collings’ brothers also served in the Army during World War I; two of them, Harry and Leslie, were founding members of the post.

Sixty-four World War I veterans, some of whom also served in the Spanish-American War, created Post 111 in December 1919. Their names are listed on a framed charter, yellowed by time and locked away in a file cabinet most of the time. Fourteen are pictured in a commanders’ photo gallery that lines the 18-inch-thick stone wall at the front of the hall.

The first post commander was Dr. Thomas H. Flesher, an Army physician who came back to Edmond to open a medical practice after the war. His résumé resembles that of many of the inaugural members. Raymond Bender was the Buick agent and Crawford Spearman had the theater. Frank Buell ran a lumberyard in town and Lloyd McMinimy owned a hardware store. William Bryan Oakes and Paul Marks were among several professors at what is now the University of Central Oklahoma. The streets of Edmond bear many Legionnaires’ names.

Post meetings were conducted in Edmond City Hall in the early years, Willis says. That came with the requirement that Legionnaires furnish the meeting room with “good substantial fixtures,” according to a stack of meeting minutes from the ’20s and early ’30s that Willis has unearthed.

Edmond was one of the first towns founded when central Oklahoma was opened to settlement in 1889. It depended on the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, and it depended on agriculture. Indeed, Legionnaire Earl Rodke milled flour and Post 111 member E.H. Van Antwerp ran Van’s Bakery. It was the quintessential town of about 6,000, complete with slights, suspicions and quarrels. Van Antwerp would not buy Rodke’s flour. That prompted Rodke to make an unsuccessful attempt at his own bakery, says Oren Lee Peters, whose great-grandfather, grandfather, great-aunt and great-uncle claimed land in what would later become Edmond in 1889.

Nevertheless, Legionnaires and members of the Auxiliary pulled together to form a stalwart group worthy of consideration when President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the WPA in 1935, six weary years into the Great Depression.

Edmond had been devastated by drought, crop failures and the economic calamity that visited itself on much of the rest of the nation. A small oil boom came and went in the early 1930s, according to background materials that later put Post 111 on the National Register of Historic Places. The schools, libraries, armories, community halls, parks and public works projects the WPA built were part of the lifeline for this community and more than 90,000 unemployed people across Oklahoma, according to historical records.

WPA funding was competitive. Projects had to meet well-defined community needs and required a city, county or other public agency sponsor willing to cover between 10 and 25 percent of the cost with cash, building materials or both. Ninety percent of the people hired for WPA projects had to be on relief.

The resulting buildings were inauspicious, the “architecture of the poor … mute reminders of the emotional distress and physical pain many Oklahomans suffered during the 1930s,” historian David Baird wrote. The American Legion “hut,” as it was called, would reflect that ethos: irregular reddish stones taken straight from a quarry to the building site at Fifth and Littler in Edmond, where they were anchored in thick bands of gray mortar.

The Edmond City Council asked the WPA for a community building, college stadium, National Guard armory, street paving and library repair services before proposing construction of an American Legion hut that also would serve as a community meeting hall. Fundraising began in the fall of 1935, and Edmond responded. Over the next year, the Legion and Auxiliary raised $2,000, Willis says. (That $2,000 is the equivalent of more than $34,000 in 2015 dollars.) At least half of that came from a Halloween masquerade party that drew more than 200 local residents. A barbecue, a benefit bridge party and a fundraising football game between Edmond High School and Foster City High School in Oklahoma City also helped, according to National Register documents.

WPA workers started clearing the site for the new 1,800-square-foot post in September 1936. A dozen men had six months of full-time work building it. Other men on the WPA payroll quarried the stone for the hut, the armory and similar stone buildings that rose around Edmond, the collective effort a boon to the community.

The price tag for the Legion hut was $8,000, including the cash the Legion and Auxiliary raised and the land and materials the city of Edmond contributed. The building was completed in time to host both the Legion’s and the Auxiliary’s 5th District Convention in April 1937.

Post 111 welcomed Oren Peters when he returned home in June 1945 after logging 511 active-duty days with the 45th Infantry Division that included amphibious landings in Sicily, Salerno, Anzio and southern France. He was there for the liberation of Rome and even had an audience with the pope. “When I got back, the first thing that happened is one of the American Legion guys came and said, ‘You need to belong. We’re having a meeting. I’ll come by and pick you up.’” The camaraderie has kept him going back for 70 of his 94 years.

Peters opted to finish two years of high school and became head football coach and senior class president. By 1947, he was Post 111 commander and a student at Central State Teachers College. That combination was fortuitous, he says. “Some of the (Legion) members were professors. One of them taught English literature. I never would have made it if he had not tutored me a little, told me what I should be doing.”

Other notable Legionnaires included the late Brown Hudson, an Army veteran who drew the maps that guided the planes that dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Post 111 was a vibrant force in the community with its blend of World War I veterans – the most active American Legion members – and an infusion of men and women just back from World War II.

“In the late ’40s and ’50s, The American Legion was the place to go,” Peters says. The oak floor in the spacious meeting hall was ideal for dances before termites forced its replacement with concrete. “You had to go to the college to find something bigger,” he adds. At least one of the monthly Legion meetings was Family Night.

Today, Post 111 is the only remaining WPA building in Edmond that is virtually unaltered, a monument to “enlightened effort by the federal government that alleviated much of the suffering” during the Depression, Baird wrote. The Legion still fulfills part of its contract with the city by making the post available to other groups. It’s regularly rented for everything from church services to family reunions. (The building is owned by the city and leased to Post 111 for $1 a year.)

Under Willis’ leadership, Wi-Fi was added with the idea that post-9/11 veterans attending college in Edmond can use the space when they need a quiet place to study.

Willis joined in 2003, a few years after retiring from the Air Force and taking a job with an aircraft renovation firm in nearby Oklahoma City. He’s worked to strengthen Post 111’s ties to the community, initiating a high school oratorical contest and establishing annual awards for the outstanding ROTC cadets at two high schools and the college.

But the past has the greatest pull. “Holding that original charter is like picking up the Constitution,” he says. “There’s a lot of history here. I find it really intriguing.”

That set him searching through old handwritten census rolls, looking up names on Ancestry.com, and digging through city records, piecing together Post 111’s story. The research is difficult because member names are often misspelled, making them difficult to find in official records.

“Back in the day, everybody did cursive writing and the letters have faded,” Willis says. “Or the person taking the census spelled the name the way they heard it.”

Indeed, a roster of Edmond residents who served in World War II, displayed on one wall of Post 111, misidentifies Oren Lee Peters as Ann Peters.

Yet it thrills Willis to find the draft card of one of the original post members or tie a family name to an Edmond landmark. That speaks to Post 111’s deep ties to central Oklahoma veterans. “As far as I know, the lights have never gone out here in almost 100 years,” he says. “That’s impressive.”

In the course of his research, Willis has also discovered two families in which both father and son were commanders: William P. Thompson and his son Lowell, who were commanders in 1935-1937 and 1956-1957 respectively, and Paul H. Coyner and his son Ray, who were commanders in 1930-1931 and 1953-1954 respectively.

Willis’ son is a post-9/11 Army veteran and a member of Post 111. “Maybe …” Willis starts reverently surveying the inside of the stone meeting hall as if he’s addressing one of the founders. “Maybe he will step up and be commander.”

Ken Olsen is a frequent contributor to The American Legion Magazine.

- Magazine