At the height of the Vietnam War, a group of wives, sisters and mothers took up the fight.

Ann Mills-Griffiths was at the home of her parents in Bakersfield, Calif., when she received the news. It was September 1966. A chaplain and the local high school football coach, also a Navy reservist, knocked at the family’s front door in uniform. Ann, then 25, escorted them inside.

“I looked at them with dread. And they said, ‘Yes, it’s about Jimmy. But he’s only missing.’” Only missing? Jimmy and Ann had been born 11 months apart: “We were very close.”

Navy Lt. (j.g.) James Mills, a radar intercept officer, and his pilot, Navy Lt. Cdr. James Bauder, had been flying an F-4B Phantom over North Vietnam when they disappeared from radar in the dead of night. No flak, missiles or anti-aircraft artillery were in the area. No explosions were seen or heard. Search-and-rescue aircraft saw nothing. Bauder and Mills had vanished.

Thus began Ann’s five-decade search for answers, a crusade initiated during the Vietnam War by many other women just like Ann: sisters, mothers, daughters and wives of missing and captive men in Southeast Asia.

This small sorority did what few women in the 1960s could. They bravely marched up to enemy headquarters on the outskirts of Paris, insisting on a seat at the diplomatic table. They defied the Pentagon, the State Department and the White House edict instructing them to keep quiet and leave diplomacy to the professionals.

Bucking tradition to fight for the men they loved, this cadre of ladies formed an organization called the National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia. Armed with elbow grease, its members became accidental activists during one of the most tumultuous times in U.S. history. And in October 1969, they secured a meeting with the North Vietnamese at a small house just outside Paris. Invited for afternoon tea, the five women found themselves staring down the enemy.

As they tried to still their shaking teacups, a stone-faced North Vietnamese diplomat stood up, pulling from his pocket a folded New York Times article emblazoned with a photo of POW wife Sybil Stockdale. Pushing it in her face, he said, “We know all about you, Mrs. Stockdale.” Sybil blinked, staring back at him. The ticking of a clock in the background mimicked her pounding heart.

Leering at her, he asked, “Does it not seem strange to you that for so many months the government was not concerned and talking about the prisoners and missing? And then the government started talking about them and women started coming to Paris. Your government is using wives and families to draw attention away from the crimes and aggressions they are committing.”

Sybil could almost feel the blood congealing in her veins. The diplomat continued. “We know you are the founder of this movement in your country, and we want to tell you we think you should direct your questions to your own government.”

This was what the U.S. government had been warning the wives for years: talking in public might hurt their husbands and hamper the government’s ability to negotiate their release.

Composing herself, Sybil ticked off a list of government offices she and other wives had visited on Capitol Hill and elsewhere. Beseeching them for information on the whereabouts and welfare of their men, they handed over a thick stack of letters – some 700 – from 500 families of missing and captive men, and requested delivery. The North Vietnamese diplomat reluctantly took the bundle but made no guarantees. He then questioned why the women claimed they were receiving so little news from their men. “I believe that letters from your husbands are being confiscated by the Pentagon or the State Department.”

With only a verbal promise from the North Vietnamese and no real expectation it would be fulfilled, letdown settled in following the two-hour meeting. Were they wives or widows? Perhaps it was the gloomy weather in Paris, or the pressure had taken its toll. The growing din of anti-war sentiment – from the media, from fellow Americans – was drowning out the women’s voices. Why wouldn’t the Nixon administration, the State Department and the most powerful military in the world do more to secure better treatment for the men and get them released?

Yet this strange tea party signaled a shift in the attention given to these women, both in the United States and overseas. Unlike the previous four years during which they suffered in silence and obscurity, by 1969 they were receiving national and international media attention. And the U.S. government and its leaders took note. Between 1969 and 1973, when the Paris Peace Accords were signed, the members of the National League of Families traveled around the world and to the United Nations, pounding the pavement and their fists in the halls of Congress, the State Department, the Pentagon and the Oval Office. They did what military family members had never before done: they became the face of international diplomacy.

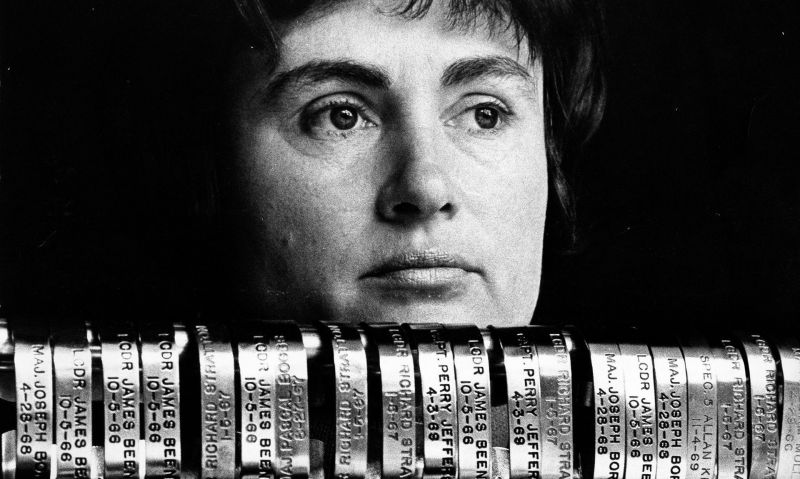

Domestically, they rallied a nation behind their cause with the wildly popular POW/MIA bracelets and the iconic black-and-white flag that now flies at the White House, the Capitol and every U.S. post office. Amid the din and confusion of the Vietnam War, the anti-war movement, civil rights marches and the Watergate scandal, these women unintentionally made the POWs and MIAs so valuable that getting them home became the only victory left for our nation. Bringing home a small group of men who represented a fraction of the 58,000 war casualties became the focus of the peace negotiations in Paris.

And at the war’s end, these women pressured the Pentagon to create a permanent government agency whose sole task was to resolve the still-lingering issue of missing men from the Vietnam War. Established in 1973, the Joint Casualty Resolution Center (JCRC) went through several name changes before becoming the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), which today has an annual budget of $130 million and a staff of 700.

Ann Mills-Griffiths took the reins of the National League of Families in 1977 and has served as a loud voice for those still missing from the Vietnam War. Not knowing what happened to her older brother for five decades was her motivation. Uncertainty is so much worse than death; it is a lifetime sentence. Yet she was also realistic: “I knew the possibility of finding his remains was remote,” she says. Until 2018, when she received a call from DPAA on a hot day in August. They called that morning, asking to see her in person. “I didn’t think anything of it because I talk to them all the time.”

This time, they had news for her. They had retrieved a few tiny bone fragments from the shallow, muddy waters off the coast of the fishing village of Quynh Phuong, north of Vinh. Using DNA samples she had given DPAA, they confirmed that the osseous material was her brother’s.

Staring at the officials, Ann admitted, “I never expected to get this news.”

Between 1993 and 2003, the case of Bauder and Mills was investigated 15 times. Then, in 2006 in the shallows of the South China Sea, a fisherman’s net snagged on something solid. Squinting over the side of his sampan, the old man saw a large piece of metal wedged in the muck. The scrap might be worth something if he could get it ashore. What he pulled out of the water was a large canopy frame of a plane. Five underwater investigations uncovered the rest of the wreckage. After that, DPAA sent divers four separate times looking for remains. They found some of Bauder, but none of Jimmy.

“When Bauder’s remains were recovered in 2017, I knew my brother was there,” Ann said. “I knew he had died and where.” But DPAA did not give up. Driven in part by the movement spawned by the League to leave no one behind and account for those missing, DPAA insisted on a final dive. “This is the last time,” Ann insisted. “I don’t want any more resources spent on my brother’s case.”

Tasked with the mission to find and repatriate all missing men, DPAA vows to stay the course until its mission is complete. On their 20th search, a diver emerged from the murky waters with buckets of sediment. Working from a nearby barge, forensic archeologists poured the muddy silt through a sieve, hoping it would catch what had been hiding in this watery grave for half a century. And it did. One of the specialists held up a tiny piece of osseous material. It was a rib bone belonging to Jimmy.

Ann’s brother was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery in 2019. But she continues to head the National League of Families, 45 years after taking the helm, because it was never just about her brother.

Before Jimmy disappeared, and long before there was DPAA, there was the U.S. Graves Registration Service, established in 1917. This unit was responsible for identifying remains after the Great War and burying them, mostly using dog tags and the accounts of fellow soldiers.

Those who were missing in war, though, were left missing – until the Vietnam War, when a small group of women changed all that and made the fate of the missing a national priority.

This same group of women also fundamentally altered how the United States considers prisoners of war, who now have national value. Consequently, the nation fights its wars in ways to minimize the potential of capture by the enemy. It was no accident that the United States ended its longest conflict in 2021, in Afghanistan, without a single POW or MIA. The nation can still tolerate those killed in action, but not POWs nor MIAs.

Likewise, this policy shift has also influenced other countries. The families of missing and captive servicemembers in Kuwait, Israel and Australia have all pressured their governments to follow America’s lead and “leave no man behind.” And Vietnamese families, having witnessed the substantial media coverage given to missing U.S. troops, have demanded their government do the same for their wartime missing.

There are 1,579 husbands, fathers, sons and brothers still missing from the Vietnam War. Their wives, mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, daughters, sons and now grandchildren continue to hold the United States and foreign governments accountable for determining the fate of each one. While the mission stipulates the United States will make every conceivable effort to leave no servicemember behind, the reality differs. The total number of missing Americans will never be zero. The job will never be finished.

Yet the endeavor is noble, uniquely and quintessentially American, and the return of long-lost servicemembers always celebrated. These exhaustive efforts to find just one missing soldier, sailor, airman or Marine are just part of the work DPAA continues to do: combing the globe searching for remains of our missing from all wars. It is the enduring legacy of a promise made to a handful of military wives 50 years ago: “Leave No Man Behind.”

Taylor Baldwin Kiland is the co-author of three books about American POWs, including “Unwavering: The Wives Who Fought to Ensure No Man is Left Behind” (Knox Press), from which this article is adapted. She is a Navy veteran and member of American Legion Post 10 in Barre, Vt.

- Magazine