Specialists tell students that the direct approach from a peer is usually the best step.

Two specialists in veteran suicide prevention told attendees of a breakout session at the 16th Student Veterans of America National Conference Friday in Nashville, Tenn., that when warning signs appear, it’s usually best to take a direct approach with someone at risk of taking their own life.

“A lot of times, when we have somebody who is struggling with thoughts of suicide, they feel very invisible,” explained Eileen Chapman of the Wounded Warrior Project, who joined her colleague Lindsey Gray in an interactive discussion titled “Let’s Talk: Suicide Prevention for Student Veterans.”

“They feel very alone. They feel like nobody’s going to get it, or that nobody wants to talk about it because it’s this big thing that they are carrying. By just saying, ‘I’m noticing these changes, and I’m just wondering, ‘Are you thinking about killing yourself?’ – you’re putting it right on the table. You’re being direct. You’re saying, ‘I’m not scared to talk about this with you. This doesn’t scare me. I care about your life, and I want to talk to you about it.’ We’re not promising to fix it. We’re not promising to fix their whole situation. We’re just saying, ‘I want to put it on the table and talk about it because I care.’” Generally, they said, that approach gets veterans at risk to open up about their feelings.

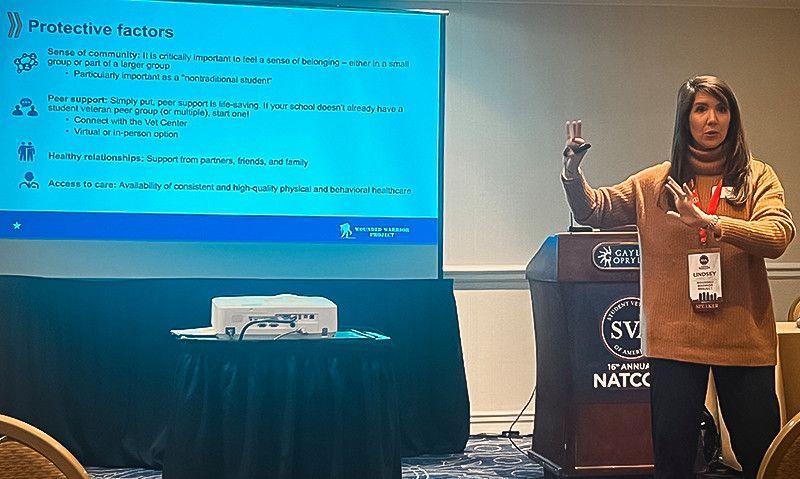

Gray and Chapman went over risk factors and warning signs, including changes in normal behavior among those who may be considering suicide and contributing stresses that often arise specifically for veterans. Among those stresses are the sudden shift from military to civilian life, the likelihood that a veteran has to balance a full-time job with classroom studies, financial struggles and debt, and the fact that they are more often than others to be single parents. “That’s a lot of stress for one person,” Gray said. She added that two out of three post-9/11 veterans have VA disability ratings and that such conditions as traumatic brain injury and chronic pain are high risk factors.

Signs from veterans at risk include frequent mention of pain, inconsistent sleep patterns, isolation and a noticeable change of appearance, from clothing to personal hygiene. Substance abuse, or “mis-use,” like the cessation of prescribed medication, are also signs. If a veteran says, “No one would ever miss me,” that is also a red flag, they said.

“Warning signs can be things we are seeing physically with someone, things we are hearing through our interactions, and then actions,” Chapman said. “You’re looking for changes. If this is someone you see regularly, speak to regularly, you know what’s normal for them, or what to expect from that person when they walk into a room or walk into class.”

By taking a direct approach, peer to peer, a veteran can make the burden of discussing suicidal ideation easier on the person at risk. “There is power in saying it out loud,” Chapman said. “I think a lot of folks get stuck on, ‘how on earth do I even approach this?’ It’s intimidating. I don’t want it to offend them. I don’t want it to ruin the relationship or the trust. But if you’re using the evidence that’s in front of you, it’s really hard for that person to wiggle out of it. Use that to your advantage. Sometimes when people … are really struggling with meds, with sleep, with finances, that could mean that they might be thinking about suicide.”

It's also important that the concerned friend understand that simply listening and caring is typically more helpful than delivering the veteran a barrage of options to try. “Listen to support not to solution,” Chapman said. “It is so tempting to throw all the great resources that we know about – to say, like, ‘You’re struggling with a job? Here’s this. You need a therapist.? Here’s this. Housing?’ Whatever. It’s so easy to do that. But when you’re in that moment of crisis, your brain goes to a pinhole view. It is so overwhelming to think of all the what-ifs.

“There is also no guarantee that those resources are going to fix anything, especially if that person is not in the right head space to receive all of that information. We are all in this field of service because we are fixers, and we want to help people, we want to give back … but when we are talking about suicide, try as hard as you can to dial back your fixer brain and just be supportive. Just validate the pain that they are talking to you about – the crap that they have been through to lead them to the point of thinking about killing themselves. It’s not as easy as one resource … If there was an easy solution, they would have already done it.”

When directly approaching a veteran with questions about suicide, Gray and Chapman said it’s important to take up the conversation in private. “If you get a yes, you’re going to be talking for a while.”

“Make sure you’re in a good place to have the conversation,” Gray said. “Make sure it’s private, so they are not looking over their shoulder to see who is listening.”

Gray and Chapman also said a “well-rounded system of support” involving other peers or peer-based programs like VA Vet Centers, veterans service organizations or other similar resources can help – keeping the burden from falling onto the shoulders of just one support person. “It can’t be just you. We are not on call 24/7, and that’s not good for the person at risk, either.” If the veteran says he or she is not comfortable with anyone else, that’s a time to look for outside support. “They need more than one option.”

Stigma about seeking help from agencies or other formal services can be an obstacle for many veterans, they said. “Peer support saves lives,” Chapman said. “Peer support changes lives. It saves lives. Feeling understood without having to give a lot of context is huge. That’s what’s unique about the military and veteran population – that kind of instant understanding without having to explain too much.”

Gray added that veterans on campus, or elsewhere, will want to not only know about local resources for support if the time comes when outside help is necessary, but supporters should personally visit them and make sure they know their hours and exact locations. At a time of crisis, a “sense of community” on campus and nearby, with other trusted veterans, “can be life-saving,” Chapman said. “I think we don’t give enough credit to peer support that’s available. We often think when it comes to mental health or suicide, this is a mental health problem, this is a counselor or a therapist issue, or I’m not qualified to do this. The reality is that people who are struggling with suicide just need somebody they can talk to. They are looking for some connection to someone who is not going to judge them. It’s not easy what you’re dealing with.”

Most important, they agreed, is to “be more intentional in your conversations with people, so that we’re not avoiding conversations that might be hard. It is hard. But their life is more important than that temporary feeling of ‘I don’t know what to say.’ And if somebody is talking with you about this stuff, they don’t expect you to be the expert. You’re a person. You’re a peer. You’re somebody they know from school. If they wanted to talk to a clinician, they would go to a doctor. They’re talking to you because you’re a person that they can relate to who they can trust.”

- News