Massive VA medical center project promises to trigger an all-new post-Katrina economy and set a 21st century standard of care for Gulf Coast veterans.

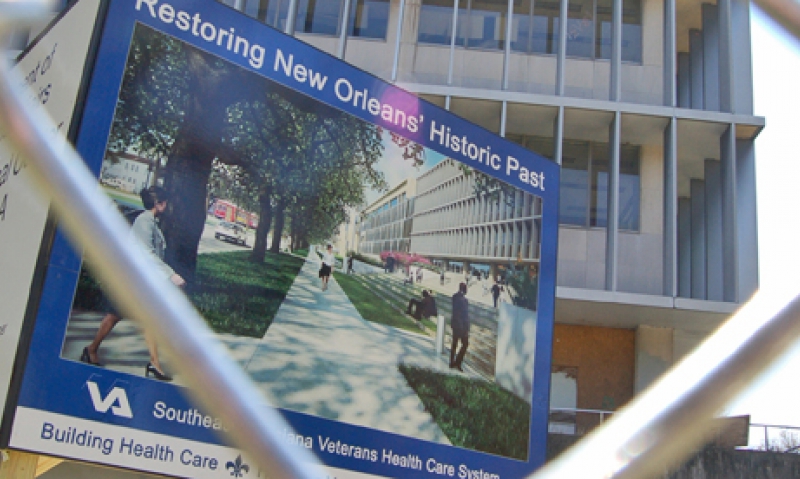

Construction is expected to begin this summer on a 200-bed, state-of-the-art VA medical center to replace the veterans hospital that was nearly destroyed five years ago by Hurricane Katrina and toxic floodwaters that poured in behind the storm. Some 40,000 veterans who receive VA care in the Greater New Orleans area have since relied on outpatient clinics, leased spaces and arrangements with local hospitals or VA facilities in distant cities to receive medical care.

Katrina and the floods wiped out all but two floors and the parking garage of the high-rise New Orleans VA Medical Center, but the catastrophe completely shut down a nearby, 1939-built public health hospital under the administration of Louisiana State University. The storm's unexpected closure of the LSU Charity Hospital left the city's uninsured and low-income residents in the same boat as the veterans: in urgent need of a replacement.

"I think it might ave been in November after the hurricane," remembers Larry Hollier, chancellor of the LSU Health Sciences Center, "... and I asked them at VA what they were planning to do. They said, ‘We'll be back in New Orleans, all 200 beds.' And I said, ‘Why don't we work together?'"

The New Orleans VA Medical Center already had long-established affiliations both with LSU and Tulane University medical programs. As is the case in most metropolitan areas, the med-school affiliation system had given the New Orleans VA hospital expert medical care from resident and faculty doctors, many of whom are leading researchers in their specialties.

An early commitment of $325 million in federal disaster-recovery money and another $300 million in VA major-construction funding quickly gave the replacement veterans hospital a down payment of more than 60 percent on a project estimated to cost $995 million when finished. A new 424-bed LSU hospital - which would combine the old Charity facility and the university teaching hospital in the city - would cost nearly twice as much, the seed of which is a nearly $500 million FEMA settlement.

Together, the VA and LSU "footprints" between Canal and Tulane Streets represent a monumental cornerstone to a bio-medical corridor many in the city see as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity - one that will attract research companies, medical-supply industry and dozens of support businesses. "I think this is the under-pinning of the economic future of the city," said Hollier, who estimates the annual economic impact of the two hospitals at about $2.7 billion. The VA project, which received $3.3 million in federal money in March to prepare the construction site, is expected to be finished in late 2013. The LSU facility is set to open in late 2014. Together, they will occupy about 70 acres of downtown property - most of which is now low-income residential and abandoned housing that was hard-hit by the storm and floods. The city of New Orleans is now negotiating the purchases of those properties in time to deliver construction-ready ground by July 31.

Historic preservationists who wanted VA and LSU to look elsewhere, primarily to their former homes near the Louisiana Superdome, have fought plans to put the new hospitals in the housing district north of the French Quarter, but their challenges have not held up in public meetings or in a recent application for a court injunction. Over 25 percent of the properties are already purchased, and nearly all are in negotiation.

In all, the 70-acre VA-LSU project is destined to become what James P. McNamara, president and CEO of the 2005-created Greater New Orleans Bioscience Economic Development District, says "will be the largest hospital construction project in the world." The estimated number of construction jobs alone, he says, is nearly 20,000 between 2010 and 2013. "This is a giant re-set button for us. The first step was the commitment by VA. That is the cornerstone we are building off of."

"This is a big project," says Julie Catellier, who moved from VA disaster-recovery coordinator after Katrina to director of the Southeast Louisiana Veterans Health Care System. She foresees a rare opportunity to build a brand-new VA medical center designed for the future. New Orleans is expected to be done shortly after Las Vegas and Orlando; the three represent the first new VA medical centers in the system since the mid-1990s. "These are going to be the flagship facilities that will put the bio-sciences corridor on the map. It really is a legacy. That is why we call it the Legacy Project. This hospital is being built for veterans who have not yet been born."

"It is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity," says New Orleans resident and American Legion Past National Commander Bill Detweiler, whose home was flooded after Katrina. "We need to do it right."

For a full story on the new VA medical center plan in New Orleans and what it means to the post-Katrina recovery effort, see the August issue of The American Legion Magazine.

- Veterans Benefits