New York psychologist, Colorado institute leader and VA suicide-prevention team tell how they and the Legion can help veterans at risk.

Dr. Frank Bourke treated and studied 850 survivors of the World Trade Center attack of Sept. 11, 2001, for 10 months following the tragedy. His patients had a common denominator: They had all been above the 100th floor when their building was hit.

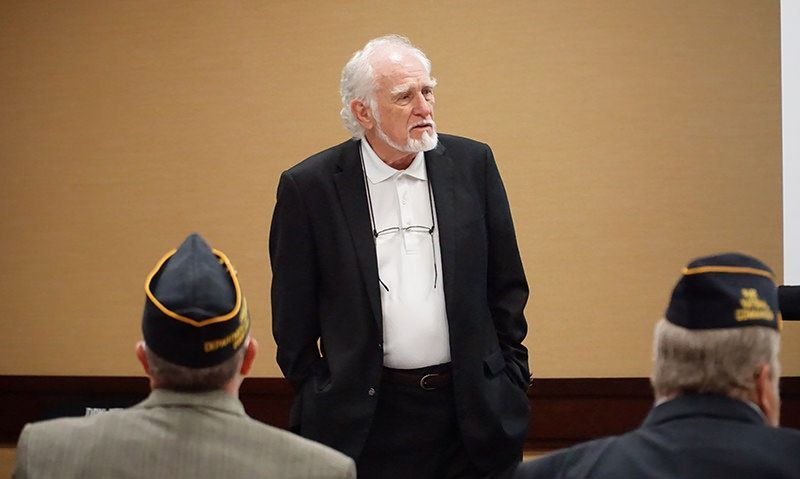

Trained as a research psychologist, Bourke joined an upstate New York team to provide much-needed and under-supplied mental-health support in the aftermath of 9/11. That experience gave him the opportunity to apply a drug-free protocol he had been using in a clinical setting – a predecessor of his Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories (RTM) to help veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. What emerged from the experience 18 years ago, he told The American Legion Traumatic Brain Injury/PTSD Committee Aug. 23 in Indianapolis, was “a real breakthrough for the treatment of PTSD. This is a little unbelievable because it works so well. The fact that it works over 90 percent of the time is really unbelievable.”

He told the committee that the protocol has been successfully tested on combat veterans in five separate one-year studies. He said veterans did not simply improve. “The veterans don’t have nightmares. They don’t have flashbacks. They don’t have PTSD.”

Calling it a “neurological intervention,” the chief executive officer of The Research and Recognition Project said the protocol involves reliving the PTSD-triggering memory, mentally reframing it and then separating it from the fight-or-flight area of the brain.

One veteran who used the protocol told the committee that he felt it worked so well after he had previously been suicidal that he went to VA to request his service-connected disability rating be reduced to zero. “I felt it immediately,” said retired Army Sgt. 1st Class Dan Jarvis, CEO of the non-profit 22 Zero that works to reduce veteran suicide. “Nightmares gone.”

His VA provider, however, told him that “PTSD can’t be cured,” Jarvis told the committee.

American Legion TBI & PTSD Committee Chairman Ronald F. Conley, a past national commander of the organization, asked Dr. Bourke about long-term results, noting that the RTM studies were just year-long in duration. “You only have had one year,” he said. “If we endorse any type of treatment, we want to make sure that we have a concrete foundation under it.”

American Legion Veterans Affairs & Rehabilitation Commission Chairman Ralph Bozella added that PTSD episodes can “come and go” over a long period of time, often latent. “And you don’t know what triggers that.”

Bozella also explained that some PTSD experiences are not related to any single memory and may be driven by long-term exposure to stress.

“We need to do the research,” Dr. Bourke said. “This thing works 10 times better than the things we are doing now, and it doesn’t use drugs.”

He explained that he had successfully used RTM protocol, or a similar predecessor, in clinical practice for years before 9/11. He also said Walter Reed National Military Medical Center is testing it now and that more counselors need to be trained in it, and their performance must be analyzed through specific measurements. The treatment is also being tested in the United Kingdom, he added. The American Legion Department of New York and Department of Florida have counselors trained in the protocol. A Department of New York resolution, Dr. Bourke explained, helped him get the funding necessary to conduct the five completed studies.

“There is no silver bullet,” he told the group. “This enables a client to deal with the anger, go back and remake his marriage, get a job or go to school. This is a tool to be put into a comprehensive mental health treatment system.”

The committee also heard from Michael Hartford, chief of staff for the Marcus Institute for Brain Health in Colorado, who shared success stories in TBI treatment using individualized alternative therapy. “Our treatment plans are not cookie cutter,” he told the committee. “We make adjustments along the way. We customize our programs and have nine years and thousands of individuals who have benefitted.”

He explained that the institute uses equine and art therapy, fitness and relaxation as tools to help veterans with TBI who, he explained, are twice as likely as other veterans to die by suicide if they don’t get help.

Hartford said the institute has plans to expand to nine other locations across the country where academic institutions are attached to VA medical centers. “We will have the ability to treat thousands of veterans a year. We are not competing. We are a force multiplier.”

Travis Field, a suicide-prevention coordinator at Roudebush VA Medical Center in Indianapolis told the committee that community engagement is one way The American Legion can help prevent veteran suicides. “We have to take the work of suicide prevention into the community,” he said. “It’s much, much broader than the hospitals. We have to be working in the community, and with others.” He said VA suicide prevention teams, which are now mandated across the country, are improving services by connecting with local programs and mental health systems to get immediate help for those in need, regardless of the characterization of their military discharges.

Field pointed out that of 20 veterans who commit suicide, only six are enrolled in VA health care. “The rest are not,” he said. “That is the challenge. How do we identify that person in the community? We have to come together. We need to locate those 14 and make sure they don’t slip through the cracks. If they are on our radar, they won’t slip through the cracks.”

He asked the committee to help get the word out about VA’s Suicide Crisis Line – (800) 273-8255 – and keep eyes and ears alert to veterans in their communities who may be at risk, in order to get VA help to them.

“The American Legion is a community organization,” Bozella told Field. “We can learn to recognize the symptoms and to raise awareness.”

- Veterans Healthcare