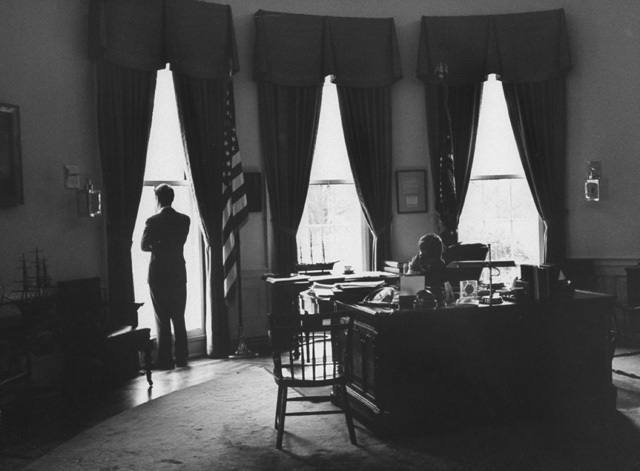

On the 50th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the men who served as America’s shield reflect on how close the world came to nuclear war.

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was vacationing on the Crimean Peninsula, just across from Turkey, when he came up with the idea to plant nuclear-tipped missiles in Cuba. “It was high time America learned what it feels like to have her own land and her own people threatened,” Khrushchev huffed.

But Khrushchev’s plan worked too well. Washington felt so threatened by Moscow’s bid to disrupt the Cold War’s delicate balance that it nearly triggered World War III.

This is part of the story of how a few brave men faced that once-unthinkable possibility in October 1962, 50 years ago this month – and ultimately prevented its reality.

“War ... At Any Moment.” The 13-day Cuban Missile Crisis was the final link in a chain of disparate events and forces – the 1961 Berlin Crisis, Castro’s revolution, the Bay of Pigs, Moscow’s sense of encirclement by Washington, Washington’s sense of falling behind Moscow, even the shadows of Munich and Pearl Harbor – that pushed the two superpowers to the brink.

Khrushchev claimed he was trying “to establish a tangible and effective deterrent to American interference ... we had no desire to start a war ... our goal was precisely the opposite: we wanted to keep the Americans from invading Cuba.”

Indeed, in February 1962, eight months before the Soviet missiles were discovered, Washington developed plans for what sounds like an invasion. “Operation Mongoose” aimed to topple Castro’s regime by employing “maximum use of indigenous resources” and “decisive U.S. military intervention.”

Three weeks before the missiles were detected, the Senate passed a resolution supporting military action in Cuba. Around the same time, the Air Force finalized a plan for tactical airstrikes in Cuba.

Then Defense Secretary Robert McNamara drafted a memo detailing six justifications for military action in Cuba, one of which was evidence that missiles or other weapons that could threaten the United States were deployed on the island.

High-flying U-2 reconnaissance planes soon confirmed the scenario.

“I was told that President Kennedy wanted blue-suiters flying missions over Cuba,” recalls retired Air Force Brig. Gen. Gerald McIlmoyle – a reference both to Air Force pilots and to Kennedy’s lingering distrust of the CIA after the Bay of Pigs debacle in April 1961.

“The CIA was not happy transferring their U-2s or the overflight of the Cuba mission to the Air Force,” adds McIlmoyle, who during the crisis piloted U-2s out of Laughlin Air Force Base in Texas and McCoy Air Force Base in Florida.

The CIA’s modified U-2s had bigger engines and more stable platforms, retired Air Force Col. Buddy Brown explains. Brown’s first U-2 mission during the crisis began, he recalls, “in one of the worst thunderstorms ever.”

Brown, who later piloted the otherworldly SR-71, says he flew “a lot hairier missions” over Asia, along the periphery of the Soviet Union and “over the ice pack” above the Arctic. But he says that the missile crisis brought us “within minutes of atomic war.”

“We didn’t know what Khrushchev was going to do,” adds Gordon Fields, who sailed aboard USS Abbot. Fields calls the missile crisis the tensest time of his 22-year Navy career. “It felt like war could have come at any moment.”

With 42 medium-range missiles, 24 intermediate-range missiles, 42 long-range bombers, 24 anti-aircraft batteries and 22,000 troops, Khrushchev’s Cuban missile base would drastically reduce the time from launch to target, giving Moscow a first-strike capability.

“ExComm” – a special committee of Kennedy’s National Security Council – wrestled with how to respond. In many ways, our generation’s debates over pre-emptive war in Iraq and Iran echo the ExComm transcripts:

n McNamara advised that airstrikes be launched “prior to the time these missile sites become operational” and warned the president’s war council to brace for the Soviet response in Europe “because sure as hell they’re going to do something there.”

n Similarly, Secretary of State Dean Rusk was concerned about a Soviet move on Berlin and advised Kennedy “to set in motion a chain of events that will eliminate this base ... whether we do it by sudden, unannounced strike or ... build up the crisis to the point where the other side has to consider very seriously about giving in.”

n Joint Chiefs Chairman Maxwell Taylor cautioned that even massive airstrikes could “never be 100 percent” effective.

n Attorney General Robert Kennedy scribbled a note that read, “I now know how (Prime Minister Hideki) Tojo felt when he was planning Pearl Harbor.”

n After meeting with former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, CIA Director John McCone reported that the old general recommended “all-out military action ... go right to the jugular.”

Prayers. Kennedy was ready to do just that. He concluded that he had four options: a targeted strike against the missile bases; airstrikes against airfields, SAMs (surface-to-air missiles) and “anything else connected with” the nuclear bases; “doing both of those things and ... launching a blockade”; and an invasion. “We’re certainly going to do No. 1,” he said. So he ordered the military into action.

For the first time since its inception in 1946, the Pentagon shifted Strategic Air Command’s readiness status to DEFCON-2, one step short of war. At U.S. bases around the world, as historian Paul Johnson details, “some 800 B-47s, 550 B-52s and 70 B-58s were prepared with bomb bays closed for immediate takeoff.” Ninety nuclear-armed B-52s began round-the-clock orbits over the Atlantic. At the height of the crisis, one-eighth of the Air Force was airborne. If the “go” order came, the force planned 1,190 bombing sorties the first day. Sixty warships were dispatched to the waters around Cuba.

Retired Navy Capt. Charles Calhoun, who commanded Destroyer Squadron 6 from the flagship USS Vesole, took a call from the Atlantic Fleet at 11 a.m. Oct. 20. “They asked how many ships could be ready to sail on short notice,” Calhoun explains. “I told them four within the hour.” The response: “Sail two right now.” When Calhoun asked where, the answer was clear enough: “Head south.”

John Kelleher, a veteran of Abbot, remembers his passage south as “anything but uneventful ... we steamed directly into near-hurricane-force winds and seas.”

Once on station, the men who served as America’s shield during the crisis didn’t learn the full extent of Khrushchev’s gamble – what Arthur Schlesinger Jr. described as a “roll of the nuclear dice” – until Kennedy’s Oct. 22 address. “Initially, we had no idea why we were being sent, no idea the Soviets had introduced nuclear missiles,” Calhoun recalls.

He adds that the rules of engagement were in flux even after the president’s address, which made for tense moments – and called for quick thinking.

Just after Kennedy’s speech, USS Newman K. Perry made contact with a Soviet cargo ship and prepared to intercept. Calhoun ordered Perry’s skipper to wait and called his commanding officer in Key West for instructions. He never knew how far up the chain of command his query went. But in minutes, the answer came back: “Regarding your last transmission, direct the Perry not, repeat not, to intercept.”

Cooler heads didn’t always prevail, however. At one point, a U.S. warship dropped a depth charge on a Soviet sub.

Still, Calhoun felt reassured by the gathering military might he saw during refueling stops in Key West. “Practically everything we had was in Florida,” he explains.

Likewise, Brown recalls flying out of McCoy Air Force Base and seeing scores of warplanes “loaded to the gills.”

“We were entirely ready to handle any contingency,” Calhoun adds.

Calhoun wasn’t the only one to come to that conclusion. As he watched the United States form a fist that October, an awestruck Charles de Gaulle reportedly remarked, “There is really only one superpower.”

Even so, a poignant letter McIlmoyle penned to his wife during the crisis reminds us what was at stake: “I know there is only one way you and I want the kids to grow up – and that is free ... It is time to take stock of the possible results if each of us doesn’t do his share in stopping the communist tide ... Make sure you say your prayers at night.”

Many Americans did exactly that after Kennedy’s speech Oct. 22.

Kennedy described Moscow’s “transformation of Cuba into an important strategic base by the presence of ... long-range and clearly offensive weapons of sudden mass destruction,” ordered a “quarantine,” summoned emergency meetings of the OAS (Organization of American States) and the U.N. Security Council, called upon Khrushchev to “eliminate this clandestine, reckless and provocative threat to world peace,” and warned Moscow that any nuclear missile launch from Cuba would be considered “an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.”

As Frank Laffredo, who served aboard Abbot, recalls, “The message was, ‘You’re in our hemisphere now, and this is the way it’s going to be.’”

Restraint. Khrushchev criticized Kennedy for “piratical measures,” but his response gave both time to contemplate their next move. As Schlesinger explained, Kennedy was “arranging the military setting that would make diplomacy effective.”

While the Pentagon braced for war, U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson made America’s case at the United Nations, famously telling his Soviet counterpart Valerian Zorin, “I am prepared to wait for my answer until hell freezes over.” When Zorin balked regarding the missiles question, Stevenson produced the damning U-2 photos, exposing Moscow’s duplicity.

The next day, Oct. 26, Khrushchev realized the foolishness of his plan, and sent Kennedy a rambling letter agreeing to remove the missiles in exchange for a no-invasion pledge.

But before Kennedy could respond, events rapidly unraveled. Khrushchev sent another message, this one demanding the removal of Jupiter missiles from Turkey. On Oct. 27, Rudolf Anderson’s U-2 was shot down over Banes, Cuba. Brown concedes that things could have veered out of control after Anderson was killed.

“It’s hard to say what might have happened,” he sighs. “We heard that they might order a surgical strike on that SAM site.”

Historian Robert Dallek notes that after Anderson was shot down, the Joint Chiefs began “pressing for a massive airstrike … followed by an invasion.”

McIlmoyle and Brown took Anderson’s death personally. “I was the primary the day Rudy Anderson got shot down,” Brown says, but Brown’s air base was “weathered in” that day.

“Rudy and I were friends,” McIlmoyle recalls. “He was my boss. He was shot down in the same place I’d been shot at two days before.” In fact, McIlmoyle notes that “a lot of us were shot at,” but he understands why the military kept a lid on such incidents.

Kennedy, mixing restraint and guile, decided not to respond to the shootdown nor to Khrushchev’s second message. Instead, he promised to dismantle the Jupiters a few months later, but only if the Soviets removed their missiles and kept quiet about the deal. On Oct. 28, Khrushchev agreed.

The crisis was over – almost.

Vesole was ordered to inspect outbound Soviet ships. Steaming alongside Volgoles, Vesole sent a message – in English – to prepare for inspection, which the Soviet vessel ignored. But Calhoun had a trick up his sleeve. During a refueling stop in Key West, he had requested a Russian interpreter. He directed the interpreter to use a bullhorn to hail the Soviet ship – this time in Russian. As soon as the skipper heard the message, “he called back, in English, ‘Good morning! We are ready.’” Vesole counted five missiles and moved on to another ship.

McIlmoyle and Brown remember Kennedy visiting them “after everything settled down,” as Brown matter-of-factly puts it. “He shook my hand and said, ‘I’ll never be able to thank you enough for bringing those pictures back so we could find a peaceful solution,’” McIlmoyle recalls.

Victory. Historians disagree about the crisis. Dallek argues that Kennedy “prevented a catastrophe.” Johnson counters that “it was an American defeat,” contending that Kennedy should have demanded “a neutral, disarmed Cuba.”

“The whole world was under the impression that Khrushchev had lost,” Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin later observed. “No one knew about the ... missiles in Turkey.”

In short, both sides could claim victory: Moscow removed missiles from Cuba, and Washington removed missiles from Turkey. Moscow secured a no-invasion pledge, and Washington forced Moscow to back down. But both sides lost

something as well. Moscow suffered a stinging propaganda defeat, and Khrushchev lost the confidence of the Soviet leadership. Out of power 24 months later, he would have plenty of time for vacations on the Crimean Peninsula. And by agreeing to a continued Soviet presence in Cuba, Washington ceded ground on the Monroe Doctrine, which had promoted America’s hemispheric dominance since 1823.

Yet given what almost happened, it’s difficult to criticize the outcome. The crisis sent the superpowers careening toward an armed conflict that would have mushroomed into nuclear war. Kennedy prevented that by employing a credible threat of force and clever diplomacy – each reinforcing the other – and Khrushchev blinked.

As Calhoun puts it, “We stood our ground and said, ‘Get those damn missiles out of there.’”

And that’s what happened.

Alan W. Dowd is a contributing editor for The American Legion Magazine. He writes the monthly “Landing Zone” column at www.legion.org/landingzone.

- Magazine