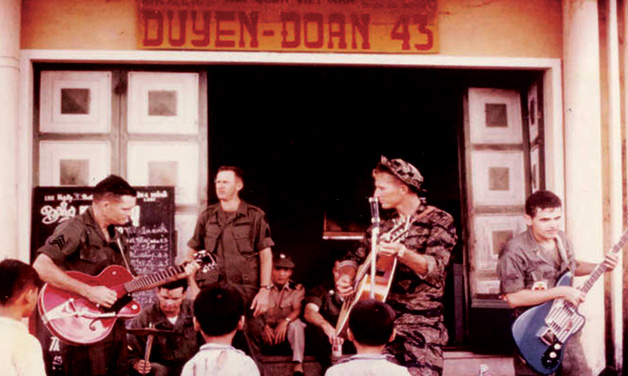

Uniformed entertainers boosted morale of Vietnam troops, no matter how deep they were in theater.

All Rick Holen wanted to do was theater.

A draft notice, slipped into his graduation card by his parents, didn’t slow him down. He enlisted in the Air Force but spent his off hours working at the historic Dock Street Theatre while stationed in Charleston, S.C. He took a bus to rehearsals every night and slept in the prop room on weekends. “I learned a hell of a lot there,”

he says.

Vietnam, predictably, interrupted. When Holen arrived in country July 4, 1969, he had resigned himself to a year away from acting. Counting, wrapping and taking the Bien Hoa base exchange’s money to Saigon seemed as far from the stage as he could get.

“I got lost one day and drove by the Army Special Services compound, and there was a big sign that said, ‘Auditions for ‘The Fantasticks,’” Holen recalls. “My heart skipped a beat because it was an opportunity – an opportunity that I wanted really bad.”

He knew the musical well, having directed and acted in it for a summer stock company. He got the part of The Mute, the only character that hadn’t been cast, and three weeks later received orders for temporary duty in Saigon. Holen figured that’s where “The Fantasticks” would run. In fact, he traveled all over Vietnam, on a tour that took him from the DMZ to the Mekong Delta, from the Cambodian border to the South China Sea – anywhere there were U.S. troops to entertain. For three months, the group flew on Chinooks,C-123s and C-130s to bases large and small, performing on flatbed trucks, bunkers, sandbags and other makeshift stages.

“I think we mounted that show in a week and a half or two weeks,” Holen says. “Sometimes we did two shows a day, sometimes three. I remember playing Freedom Hill up at Da Nang, and about halfway through the show, about 12 Marines came in and sat down in the front row. They had all their gear: M60 machine gun, M16s, hand grenades hanging off their belts. About 15 minutes into the second act, there are some love songs between the boy and girl, and these guys were crying. They had dark spots all over their uniforms, like mud. When the lights came on, I saw it was blood. They’d just gotten out of a mission. It was hard to process that kind of a moment.

“Once you were cast in one of these shows, you played your heart out for these guys.”

* * *

Between 1966 and 1971, 114 Command Military Touring Shows (CMTS) units performed in active combat areas in Vietnam – locations considered too dangerous for most celebrities and too remote for big USO tours. Nearly 600 U.S. servicemembers participated in CMTS, including a few female civilians employed by Army Special Services.

“Most of them didn’t carry a rifle and most of them weren’t wounded, but these were people who were drafted and did their jobs and had a talent that was able to build the morale of the troops,” says Hershel Gober, a former acting secretary of VA and retired Army major who served two tours in Vietnam. His singing and songwriting caught the ear of Gen. William Westmoreland, who asked Gober to put a band together and perform for men in the field. The Black Patches went wherever their music could do some good, whether it was the camp of a 12-man Special Forces A-team or a hospital full of critically wounded soldiers who watched from their beds.

“We never set a limit on our shows,” Gober says. “As long as they wanted us to play, we’d do two or three shows for the same group of people. They just liked to hear music they knew and to think that somebody really cared about them having a chance to just sit and relax and listen.”

When he went out, Gober wasn’t just playing music. He was evaluating the mood of the troops for Westmoreland, who saw the need to revive the old “soldier show” concept – GIs entertaining GIs.

Dozens more bands followed: country, folk, rock ‘n’ roll, jazz, soul. Army Special Services staff had ‘thousands of hobby cards filled out by military personnel entering the country, and someone who played guitar or was in a garage band back home was invited to audition. Those selected had only a few days to put together a song set and head out on tour.

Ken Holezki, a drummer from Michigan who was drafted into the Army, played in two CMTS bands: Raspberry Fig Tree and Mixed Bag.

“The response from the troops was great,” he says. “But performing for the guys who had just come out of the bush and back to base camp was always special to me. You could see on their faces that they were tired and were somewhere you would not want to have been.”

After his first tour, Holezki returned to the 10th Transportation Company in Long Binh, carrying a letter from Army Special Services requesting he be released from his unit for another two months. His captain said they were scheduled to invade Cambodia in two weeks. Holezki told him that he felt he was doing more for his country entertaining the troops than driving trucks.

“Do what you need to do,” the captain replied. “I think I can find another driver to replace you.”

There were solo acts, too. While celebrating the recording of his rock band’s first album in San Francisco in 1967, Bill Ellis was drafted. Liberty Records subsequently canceled the release, and the young man traded his guitar for a rifle as a grunt in the 1st Air Cavalry. But after a few months, a guitar found Ellis, and he was asked to perform for the officers’ mess, a CBS radio show in Saigon and firebases in the 1st Cav’s area of operation.

“I’d go out there and spend the night many times, then come back in, grab another chopper and go somewhere else,” he says.

Soon Ellis linked up with CMTS and traveled the length and width of Vietnam, singing “Firefight,” “Freedom Bird” and other songs that were a salve for soldiers grieving the losses of friends, fearful they might not make it home themselves.

“They’d really break down, and it brought out the emotion,” Ellis recalls. “I talked to a colonel and said, ‘Should I be doing this? It really seems to have an effect on people.’ He said they felt it was good because it was a relief.”

* * *

In 1968, the Army drafted Robert Silver, an aspiring actor who’d finished law school at Columbia University in New York and was pursuing a master’s degree in theater there. The day after Thanksgiving, he was on his way to Chu Lai to work as a personnel specialist for Headquarters Company, 23rd Infantry Division.

Meanwhile, the USO and Army Special Services were preparing to launch a production of “The Fantasticks” in Saigon, but an airman cast in one of the roles had to be medevaced after he was wounded by a taxicab bomb. A woman who’d worked with Silver in community theater when he was stationed at Fort Jackson, S.C., recommended him for the part.

“While I was there, I became aware of CMTS, which at the time was really a music program,” Silver says. “I thought, ‘Why not send out something like a play or a musical?’ So I suggested it to Brad Arrington, who ran CMTS, and he asked me to write up a proposal about how it could be done.”

Silver helped assemble “The Maniactors,” a musical revue with a couple of blackout sketches, three Harold Pinter revue sketches, and original tunes by Jay Kerr, an Army entertainment specialist stationed in Bien Hoa who created touring shows for the 1st Cav. He ended up touring with the revue as an accompanist.

Higher-ups in Saigon had reached out to Kerr, who had written for Princeton’s Triangle Club and worked for the CBS children’s television series “Captain Kangaroo” before he was drafted.

With four guys and a girl – Jan Brantley, a talent scout and producer for Army Special Services and the first woman to travel with a show in Vietnam – “The Maniactors” went to small firebases and aircraft carriers alike.

“It went over like hotcakes,” says John Akers,

an Army chemical specialist who toured with a CMTS band called New Generation before joining “The Maniactors.” One of his favorite memories is the warm reception they received aboard USS Kitty Hawk.

“I felt like a Hollywood star,” Akers says. “Many of the sailors visited with us afterward to ask about what was going on in the States. They thought we were USO. We had to tell them that we were there in Vietnam as soldiers.”

Military entertainers in Vietnam had a job to do and did it. They also acknowledge that those who saw combat had it far worse.

“I had a good time,” Kerr says. “I have a sense of guilt about that. But I was much more valuable to the Army playing the piano and writing songs than I would have been missing the enemy because I couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn.

“It was never like work. It was enjoyable. I know that on one of our USO tours our helicopter was hit by enemy fire, but I was napping and had no idea it happened. It was a blessed life. If you had to go through the war, it’s the way to have done it.”

* * *

On the heels of “The Maniactors,” CMTS staged “You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown,” written by Clark Gesner, a friend of Kerr’s. This was the unofficial first nonprofessionalproduction of the hit musical – and the troops loved it.

“We had one round-eyed girl in our show,” jokes Gary Branson, an infantry squad leader who was tapped as pianist and music director after winning an all-Vietnam talent competition. “If nothing else was received warmly, she was.”

Initially, the show couldn’t find a female lead, so Kay Johnson – Army entertainment director for III Corps – stepped into the role of Lucy. “I’d never performed in a play, so it was a big deal for me,” she says. “I traveled the entire country with nine enlisted men and lots of equipment.”

The group went from Da Nang in the north to Can Tho in the south, with stops in Pleiku, Qui Nhon, Nha Trang, Cam Ranh Bay, Cu Chi, Bien Hoa and Saigon. “Seemed like we were always waiting for a ride to haul our sets, electric piano, luggage and us,” Branson says.

Travel was usually an ordeal. En route to Da Nang, they took ground fire, and the pilot stood the plane straight up on its tail, throwing everyone and everything that wasn’t strapped in around the cargo bay. Complicating matters, the troupe’s van had a flat tire on the way to the theater.

“Needless to say, we were late arriving, and ‘Gone With the Wind’ was entertaining our audience,” Johnson says. “When the motion picture was halted, the crowd booed, but they forgave us once we got under way and even gave us a standing ovation at the end.”

Another time, leaving Pleiku, the group’s helicopters never arrived. They waited for hours before boarding a bus that took them on unsecured roads to their next performance.

If it wasn’t pouring rain, the weather was suffocating. “The heat was so intense that it actually bubbled the paint of the roof of Snoopy’s doghouse,” Johnson says.

But these moments were outweighed by plenty of good times, such as taping a TV show in Saigon, performing for a room full of brass at MACV Headquarters at Tan Son Nhut and, really, any show where they knew they were breaking up the boredom or fear of daily living for GIs.

“I went from sloshing through the paddies to playing piano for a show about fictional 6-year-olds in a few days’ time – a rather stark contrast,” says Branson, who was an infantry sergeant assigned to B Company 4/9 Infantry, 25th Infantry Division, at Tay Ninh.

“I felt guilt about leaving my men in the boonies, but happy to be out of the field. Those same feelings are still with me to a certain extent.”

* * *

Shows continued to be big events in the field until U.S. forces began to stand down in 1971. CMTS organized productions of “The Odd Couple,” “Barefoot in the Park,” “The Star-Spangled Girl,” “The Private Ear” and “The Public Eye,” and “The Roar of the Greasepaint – The Smell of the Crowd.”

Knowing that a lot of soldiers had never seen live theater, Holen and his “Fantasticks” castmates were buoyed by positive reactions. “A guy from Brooklyn came up to me after a show and said, ‘When I get home, I’m going to go to every Broadway show I can. That was quite moving.”

Jim Lorenzen, who joined the musical after a short time at Long Binh’s data center, heard an even better one while having drinks with some Green Berets or Marines – he can’t remember which – after a performance.

“One was a big, burly guy you’d expect to see jump out of a plane with no parachute. He said, ‘I’m glad to see some culture here. Those guys are a bunch of animals. They don’t appreciate this stuff.’”

Audiences, though, didn’t always know what they were getting.

“The people who met us at each of the places we were going to do the show tended to ask, ‘Are you guys the band?’” says David Adamson, who was cast in “The Fantasticks” after a few months as a darkroom technician with the 1st Military Intelligence Battalion north of Saigon. “We finally stopped correcting them and said, ‘Yeah, we’re the band,’ because it was too hard to explain that we did a play.

”If troops wanted to hear music, they wanted to see girls even more.

“Sometimes you would hear ‘Take it off!’” says Lynn Skynear, who played The Girl in “The Roar of the Greasepaint – The Smell of the Crowd.”

“You’d get the cat whistles. They must not have seen that I looked almost anorexic. I think I walked away saying, ‘Wow, I must be pretty glamorous!’”

Having spent four years as an air operations specialist, Skynear left the Air Force and worked for an Australian war correspondent before taking a UPI stringer job. By 1971, she was “Vietnam-ed out” – sick, exhausted and down to 98 pounds.

She learned through a friend about an actress who had to bow out of a production, and the director needed a woman fast. “Somehow that just seemed like such a bright light,” Skynear says. “There was something so positive about it. So I said yes to this with zero talent, and suddenly I’m put with the most talented people.

“I can assure you that I was neither an actress nor a singer. An American woman was hard to find, so they were stuck. When you couldn’t get Raquel Welch, you had to settle for me.”

Kent Monken remembers Skynear well. While working as a company clerk in Cam Ranh Bay, he was cast as the lead in “Greasepaint.”

“The play needed a woman,” he says. “What group of GIs is going to see a musical of all men?” In fact, the first two scenes are just male characters, so Monken had Skynear come out early and stand around as the male characters talk.

“It worked better,” he says, chuckling.

When Monken returned to his unit, his fellow soldiers had a new respect for the actor. The first sergeant, however, did not and punished him by making him night guard at the motor pool.

CMTS entertainers may have been popular in the field, but getting approval to leave their units for two or three months wasn’t without hurdles.

Holen had to go to a full-bird colonel at Long Binh for the green light to do “The Fantasticks.” Kerr promised his commanding officer that 1st Cav would get more shows than it was entitled to if he could go on tour. Silver was arrested when his show came to Chu Lai – even with just two months left in country; he’d been gone longer than his orders permitted, and he had to arrange to get a newcomer with his MOS to replace him so he could keep performing.

CMTS organizers didn’t have it any easier. “As a producer, the most disappointing thing was not getting one pianist I needed,” Brantley recalls. “His MO was chaplain’s assistant, but his extra duty was playing dinner music for the general. The chaplain was willing to give him up for 30 days, but the general was not.

“The nicest gesture was a communications unit with only 25 men offering five of them for 30 days. They sang a cappella and were delightful guys who could be sent to any situation and didn’t need an electrical outlet.”

* * *

Sixteen years ago, Holen began looking up his “Fantasticks” castmates. With the help of Ann Kelsey, who ran the Army Special Services library at Cam Ranh Bay, he widened his search to find other CMTS veterans. Nearly 50 attended a reunion in New York, and they traveled to Vietnam in 2001.

After the war, many picked up their careers where they had left off. Kerr became a vocal instructor with his own midtown Manhattan studio, and is currently artistic director for the Fort Salem Theater in upstate New York. Silver’s résumé is full of commercials, off-Broadway shows and episodic television. Adamson teaches in the Department of Dramatic Art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Ellis wrote “Beyond the Wall,” a rock musical based on his experiences in Vietnam.

Others went in a different direction. Holezki retired after 31 years with the U.S. Postal Service, though he continues to play music. Akers spent 21 years on active duty with the Army, then entered the computer industry.

Lorenzen left performing entirely. Prior to being drafted, he had acted and directed theater in Chicago, and did some broadcasting to pay rent. “Everything was about advancing my career and becoming a star,” he says. “I got to Vietnam and started performing for those guys and saw what they were going through. It changed me. All of a sudden, it became about the audience, and the audience wasn’t the same. Performing in Vietnam seemed important. Performing here just didn’t. No one would miss one less entertainer or actor here. There was no difference to be made.” He went into finance, then publishing and finally consulting.

A retired theater professor, Holen is working on a documentary about CMTS titled “Theatre Vietnam: Stages of Healing.” In interviews, the former entertainers describe what it was like trying to lift troops’ spirits even as the war chipped away at their own. They remember the cheers and beers after the shows, but they also think a lot about the men who didn’t make it home.

Holen can close his eyes and picture the soldier in a wheelchair whose face turned gray and head fell forward during one show. Akers is haunted by a strike that wiped out advisers and elders in a village where his band had just played. And Holezki hasn’t forgotten the day he arrived by chopper to sing for an Army unit in the delta. Only seven soldiers survived an ambush. He rode back to Bien Hoa aboard a plane with 70 body bags.

For Holen, reconnecting with his CMTS brothers and sisters has strengthened his belief that they did something unique for troops in a difficult and ugly war.

“When we had our reunion, you could pick up a conversation with anybody in that room,” he says. “It wasn’t like a high school or college reunion. There was something magical about it because we all had the same kind of frightening, joyful experiences. This has been therapy for me.”

Matt Grills is managing editor of The American Legion Magazine.

- Magazine