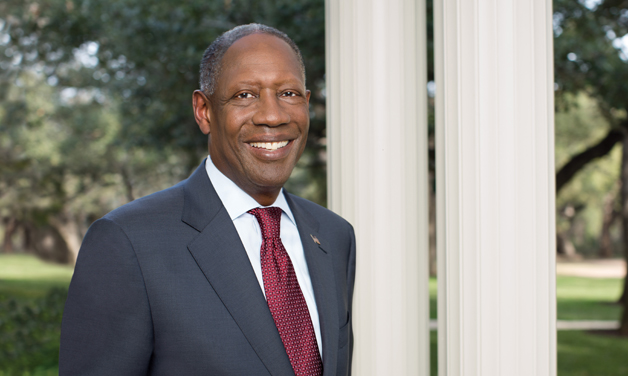

Former aerospace engineer and retired Air Force general brings a unique mix of experience to USAA, The American Legion’s preferred provider of financial services.

Science and art are not mutually exclusive terms for retired U.S. Air Force Gen. Lester Lyles, chairman of the board at USAA, The American Legion’s preferred provider of financial services. To him, the terms are connected. He has always been a math and technology guy, having spent much of his career in and around aerospace engineering. His art, meanwhile, can be found in the motto next to the January 2013 announcement of his chairmanship on the USAA website: “communicate, communicate, communicate.” That aspect of his character was recognized in 2012 with the Air Force Academy’s Thomas D. White National Defense Award, which honors contributions to national security and includes a requirement that recipients also know how to deal well with people. “The taking-care-of-people part,” Lyles said after receiving the award, “makes me prouder than whatever scientific, engineering and management things I have accomplished.”

Over the years, that combination of traits has produced a galaxy of opportunities for Lyles, son of a World War II Tuskegee Airman, whose life of service began in a high-school Junior ROTC program in his hometown of Washington, D.C. Since then, Lyles has earned multiple college degrees, helped build rocket launchers, led the Air Force’s massive Materiel Command, assisted Dayton, Ohio, through BRAC (Base Realignment and Closure) transitions, served as vice chief of staff of the Air Force, provided business leadership for a number of defense contractors, and now helps guide USAA, which serves 10 million military veterans and their families.

The Lyles dossier is loaded with medals, awards and achievements. Rarely mentioned but meaningful to him is a characteristic that brought him to Indianapolis last May. “I am an avid auto-racing fan,” Lyles said before the engines started for the 97th running of the Indianapolis 500. “It’s the engines – the technology involved – I find very interesting, very invigorating. Nothing excites me more than hearing the sound. I love racing.”

Lyles, who joined Legionnaires to watch last year’s historic 68-lead-change race, recently spoke with The American Legion Magazine about his journey to the chairman’s seat at USAA.

You have had such a diverse career: engineering, the space program, missile defense. How do all those experiences help you at USAA?

I have been very lucky. I have been blessed to have had the opportunity to command and lead large organizations, the last of which was Air Force Materiel Command, which had 82,000 people in it, and our annual budget was about half of the Air Force’s budget – about $40 billion a year of taxpayers’ money. That sort of fiscal environment, even though for the Department of Defense there is not a profit-and-loss situation like with business, we are stewards of the taxpayers’ money. We have a board of directors for the military, if you will – almost 500 in Congress – who watch everything that we do very carefully. You learn to manage large institutions. You learn to manage large groups of people. You learn to delegate. You learn what it takes to run a big institution.

For you, this all started in a high-school Junior ROTC program. Were you naturally drawn to ROTC and military service, or was it something you did to please your family?

No, not at all. Even though my father served in World War II and the legendary Tuskegee Airmen, he was not a pilot. He was an enlisted supply guy in the 99th Pursuit Group. But in Washington, D.C., when I went to high school there, all the public high schools had Junior ROTC programs. Whether you had a military affinity, background or not, you were automatically exposed to it if you were part of the public school system. It was mandatory. Parochial schools and Catholic schools did not have that, but in public schools it was mandatory for males to be part of the Junior ROTC program. I don’t remember when they stopped that in D.C., but it was years and years ago. That was my first exposure to wearing the uniform and to the discipline of the military environment and training.

You obviously excelled at Junior ROTC and in the classroom. What were your options coming out of high school?

I turned down an opportunity to go to the Air Force Academy, and when I went to Howard University in D.C. – one of the historically black colleges – it also had ROTC mandatory for the first two years for all male students. So after two years, if you wanted to be part of ROTC for your remaining two years, then you signed up with the Army, Air Force or Navy – whichever one had a program there. I was part of the Air Force ROTC at Howard and enjoyed it. I got an Air Force ROTC scholarship in addition to other scholarships there. So I signed up for the other two years. Four years of ROTC obligated me to four years of active duty.

Did you expect to only serve four years of active duty?

I was a young engineer, and I was anticipating working as an engineer in the Air Force, preferably with high technology and space programs, for four years. Then I would get out and do other things, in the private sector.

Instead, you ended up spending 35 years in the Air Force.

As my wife says, “35 and a half years.”

ROTC programs like that must have cultivated many officers who might not have otherwise pursued military careers.

Just like me, who had no other background or even understanding of what the military life was like, it was exposure to both the opportunities and the discipline. That led a lot of people to continue into the military, some of whom stayed, some of whom did not. Still, they had an opportunity they would not have had previously.

While you were a student, did you have a natural interest in complex problem-solving?

For some reason, I always enjoyed math. I always enjoyed technology. I enjoyed understanding how things work, taking things apart and putting things back together – not always successful in the latter. I loved the space program, which was obviously really big in the 1960s. That was my main interest.

How did the Air Force help you fulfill that interest?

My first assignment out of undergraduate school was directly to graduate school. The Air Force gave me a scholarship to go get a master’s degree in engineering, so my first assignment was at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. And after I got my master’s degree there, my first real assignment, if you will, was at Los Angeles Air Force Base – our space and missile organization in Los Angeles – and I was assigned as, literally, a rocket scientist. I was a rocket structural and propulsion engineer for one of our space-launch vehicles. It was my first big exposure to space programs and to running large activities.

It was the Air Force’s space program – launching satellites and things of that nature. The specific vehicle I was responsible for was the Atlas space-launch vehicle, which was used for Mercury and all those sort of things. Atlas and Thor ... I was a young lieutenant and engineer for those programs. That was my first exposure. Subsequent to that, I ended up coming back to Los Angeles as a colonel to run what we called the space-launch recovery program. That was after the tragic Challenger space-shuttle accident. A lot of people don’t know that around that same time, the United States lost one of our expendable launch vehicles – an unmanned one – and because of the shuttle accident we stood down, literally, for three years, not having any way to launch satellites because we were trying to find out what had caused the problems. Then we developed a whole family of new space vehicles. I was responsible for that, as a young colonel, in 1985.

I came back in 1994 as a three-star, to run the space organization in Los Angeles for a couple of years, and from there got called up to the Pentagon to run our Star Wars program – our missile-defense program.

Along the way, did you consider going into space yourself?

I did apply for the astronaut program and was accepted by the Air Force for a recommendation to NASA. I didn’t make the final cut with NASA. I still had lots of other involvement as an engineer and a manager.

Where do you think America’s space program stands now?

In all honesty, the space program is still fairly robust. When the shuttle program shut down, most people thought that was the end of NASA space activities. But we still have a very active space-exploration program.

I had the honor and opportunity to serve on President Bush’s space-exploration commission back in 2004, to determine what the future of space exploration was going to be for the United States. I subsequently served on what was known as the Augustine Committee. Norm Augustine, former CEO for Lockheed Martin, was commissioned with a small group – Sally Ride, God bless her soul, and others – to review what should be the future of NASA’s human spaceflight program. That was in 2009, after President Obama came into office. I have done a few other commissions and studies on space.

Are you still involved with it?

The answer is yes. I am a member of the National Academy of Engineering – the Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board. As a result of that, I stay active with NASA. I am an ex officio member of the NASA Advisory Council and have been since 2004. So yes, I am still active.

Another complex problem you have been asked to help solve is base realignment and closure transitions. How active are you with BRAC today?

Well, you are never really active with BRAC, but you can be part of the activities to advise communities and others on how they should deal with it. From that standpoint, everybody is watching closely to see if there is going to be another BRAC. The Dayton Development Coalition and some of the other entities in Ohio – I help advise them in case there is another BRAC. We also did that in 2005.

When I retired from Dayton – from Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, which was my last assignment – in 2003, I stayed active in the community in a couple of different capacities. I was on the board of trustees for a couple of different universities. I was on the board of directors for their public utility. Those things kept me involved in the community, in addition to the things I did at Wright-Patterson, in the technology activity. So, from that standpoint, I was asked – and am being asked today – to occasionally advise them on how to answer potential BRAC questions that may come up.

It’s a tough issue for communities that depend on the economic impact of a military installation. How do you approach it?

You have to look for opportunities for partnership, ways to work with industry and other communities. To me, the right question is: what is the value of a particular base, both to the country and to the particular service? The No. 1 thing is to make sure communities are addressing the right questions and not just trying to protect jobs. That is obviously their No. 1 objective, but they really need to think in terms of what is the value to the country of that particular entity.

Do you see the BRAC process as never-ending?

It’s certainly a continuous question, and I dare say a continuous need. To be honest about it, we have more infrastructure than we really need in today’s military. NASA is the same way. NASA has more installations than they really need for their mission. Looking at real life, looking at potential closures, to me, is something that’s going to be with us for a long time until somebody right-sizes those organizations.

You will see a lot more joint bases like what’s happened in San Antonio. It seems very strange to refer to what I used to call Randolph Air Force Base as Joint Base San Antonio, where they are partnered with the Army and their facilities. There is a lot more dual or multiservice activity on a base now, rather than one single service. And that’s the right thing to do to right-size.

Between aerospace engineering and a fast-evolving military, you have been at the forefront of many major shifts in American society, including communications technology. Have USAA’s breakthroughs in that area been an attraction to you as you have served on the board?

Yes. I certainly see its role growing and growing and growing, almost exponentially. When you look at the proliferation of mobile devices everywhere with everybody, particularly the millennial generation and Generation Z, or whatever you call the next generation – they are doing business through those devices. If we are going to be communicating with them, if we are going to make it possible for them to communicate with us and do business with us, we need to figure out exactly the ways to use that device – and whatever may come after that. At USAA, I am just really pleased with what we are doing in that area –in the area of innovation in general – particularly information technology. It’s a huge enterprise.

I am still involved in some companies and activities that are in (communications technology) research and development. It’s not surprising for me to say, “Go look and see what USAA is doing. You would be surprised.” It’s not just your father’s and mother’s insurance company. There are great and innovative things going on.

USAA does have to be your father’s and mother’s insurance company, too, right?

Yes. We have to appeal to both constituencies – all constituencies. We just finished a big strategic planning conference, and the big question there was, “How do we appeal to and make sure we are serving the older generation – who are going to be with us for quite a long time, Lord willing – and the millennial generation that’s coming along today, and then future generations? How do we make sure that we are appealing to, and making business easy, for all of those?”

Through their smartphones?

You go to some countries, even some what we would call Third World countries, and everybody has a mobile device and they use it for everything. In a lot of respects, I think the United States is catching up to a lot of other countries.

All this reliance on digital media does not diminish the need for personal customer service, does it?

Our core value, our motto – that “we know what it means to serve” – we take that to heart. We have to make sure that we make it convenient for our members, for them to touch us and for us to touch them, in whatever ways we possibly can.

The American Legion and USAA recently renewed its relationship. How do you assess it so far and envision its future?

It has grown tremendously. It is the largest affinity association (relationship) that we have. We don’t see that changing. I see the opportunities growing as we look at ways we can serve new members through the Legion and make them, and anybody associated with the Legion, aware of our products and services, and ensure that they understand who we are, how we serve them and how well we will take care of them. I just see the relationship growing.

Jeff Stoffer is editor of The American Legion Magazine.

- Magazine