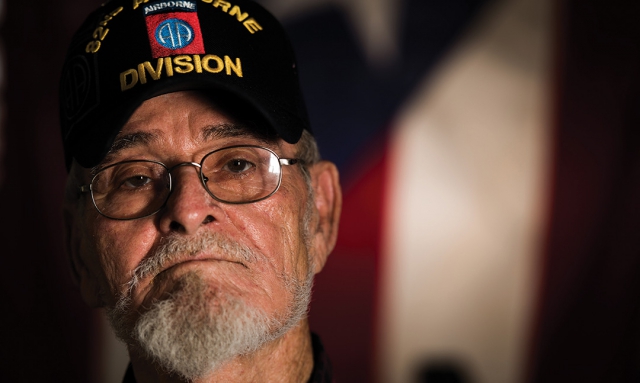

Jorge Otero-Barreto – the “Puerto Rican Rambo” – was a warrior during Vietnam. Today, he’s still supporting his comrades as a post service officer.

All the windows and doors are open, letting a warm summer breeze waft into Vega Baja American Legion Post 14, about 30 miles west of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Inside, the post commander, who doubles as post service officer, sits at a fold-out table with pens, paper and resource materials neatly arranged. He is patiently assisting a veteran who stopped by the tiny post building with questions about her VA benefits.

It’s a stark contrast to the life the commander led 50 years ago. Jorge Otero-Barreto – who volunteered for five tours in Vietnam, engaged in more than 350 combat and aerial missions and was wounded five times – is among the most decorated Vietnam War veterans, with more than 40 military honors that include multiple Silver Stars and five Purple Hearts.

His exploits on the battlefield earned him adulation from his troops and the nickname “Puerto Rican Rambo.”

FROM MED SCHOOL TO THE JUNGLE Eloy Otero and Crispina Barreto named the first of their six children Jorge (Spanish for George), in honor of the first U.S. president. His mother wanted him to grow up and become a doctor, which he originally pursued. His father encouraged him to consider a military career, and he pursued that, too. But as Otero-Barreto says, “Fate had its own way.”

After three years of studying biology at the University of Puerto Rico and two years of training at the university, Otero-Barreto joined the U.S. Army on Sept. 15, 1959. He completed basic training at Fort Jackson, S.C., and jump school at Fort Bragg, N.C., before he was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division and later the 101st.

He trained in Hawaii, the Philippines and Thailand before departing for Vietnam. “We were trained,” he says in a soft, serious tone between appointments in Post 14.

“We were prepared to do whatever we had to do against the enemy.”

Before the Army was officially in-country, Otero-Barreto helped conduct basic training for anti-communist Vietnamese fighters there. “They were farmers. They were trained to be jungle fighters. It’s not that simple.”

Otero-Barreto, a former platoon sergeant, trained his infantry teams both mentally and physically to become “jungle rats .... We liked to be inside the jungle. I know that a person has to control his mind and his body. Mental and physical courage should prepare you to take care of anything. I was willing to kill. I was willing to die. I was willing to take a cyanide pill. I am a warrior. I believed that, and I still believe that. I am still willing to take a pill instead of being a squealer.”

MIND OF A WARRIOR Otero-Barreto held himself and his troops to a high standard. In training his men, he expected them to become warriors just like him.

“A warrior is somebody who is beyond himself,” he says. “He doesn’t love himself. A warrior is a person who is willing to give his life for his people. A soldier is not a warrior until he convinces himself of the mission purpose. A warrior has to be a special person. You can see it in their faces – they are warriors.”

He recalls one time when his platoon ran into heavy fire from a machine gun. He ordered one of his men to take it out. “Remember what I taught you?” he said to him. “Go out and do it.”

The soldier followed orders and, in doing so, kept the platoon safe.

“If you don’t obey orders from me, you are a dead dog,” Otero-Barreto told his men. “You will never make it.”

He made an impression on everyone from privates to commanding officers.

Retired Lt. Col. John Hay was Otero-Barreto’s platoon leader for about six months in the late 1960s. “I noticed immediately the first night or so we were out, he was very acutely aware of his surroundings,” Hay recalls. “He was somebody I immediately trusted. He was that kind of guy. He was friendly, but he was all business, an extremely professional noncommissioned officer. For a young noncom, he was very mature. He was extremely conscientious. I trusted him with my life, I guarantee you that.”

Often, Hay was on the radio, communicating with leadership or calling in airstrikes or directing other maneuvers. He says he never worried about what Otero-Barreto was doing.

“Otero was amazing,” Hay says. “While I am looking at the mission and trying to accomplish whatever we were doing, he was just everywhere. The troops loved him, and they still love him today. He just left such an impression.”

One time, Hay remembers, Otero-Barreto admonished his troops for not respecting a deceased female Viet Cong fighter.

“He was a man of great morals, which I admired,” Hay says. “That’s something I demand from my leaders. Sometimes in war, you get tired of the booby traps and you want payback. But (what Otero-Barreto did) was never illegal, immoral or any of that. He was just a good all-around person. When you are talking about a guy who is as decorated as he is, morality doesn’t often come to mind. But it should.”

Hay, who retired after 31 years of service that included stints as a noncommissioned and commissioned officer, said Otero-Barreto was unparalleled on the battlefield.

“No one was a better platoon sergeant than Jorge – no one,” Hay declares. “I’ve had good ones, and some not so good, but no one can compare with Jorge. He was the best. No question about it.”

THE ‘REAL RAMBO’ Hay and others attribute Otero-Barreto’s battlefield savvy to his instincts and knowledge. “I was trained in conventional warfare, but (in Vietnam) I learned about guerrilla warfare, which I learned from the enemy,” he says. “To defeat that tiger, I had to know that tiger.”

In his hometown, there’s a song describing Otero-Barreto as the “real Rambo” – someone who actually saw combat, unlike the well-known Hollywood movie character: “He is the one who goes. He is the one who stays. He is the one who is real. He is the one who chose to fight. The one with courage and plenty of willingness to fight. He is Rambo.”

Otero-Barreto doesn’t like the character’s actions in the “Rambo” movies, but he embraces the nickname.

“The best Rambo is in my gut,” he says. “Saved my life in Vietnam. Took care of me in Vietnam. He told me when to fight, when not to fight, when to push, when to withdraw, when to kill.”

Throughout his deployments, Otero-Barreto suffered wounds but always returned to the battlefield. His men and platoon leaders were counting on him.

Otero-Barreto was wounded five times, but he insists he never had PTSD. “You know why? Because I was trained so good. That was my job. I was responsible for my people. I used to enjoy the fight. That is what I learned: to fight.”

UNHAPPY HOMECOMING Otero-Barreto returned home from Vietnam on Dec. 15, 1970. It was not pleasant. “When I came back from Vietnam, nobody wanted us. Nobody. They were hating us.”

He remembers being spit on by protesters and people “looking at me like I was a monkey.”

Even so, he didn’t react or fight back. “I kept complete control,” he recalls. “When I was in the jungle, I didn’t fight the enemy when they wanted to fight me. I fought them when I wanted to fight them. The same principle applied.”

At home, Otero-Barreto reunited with his young wife and baby. Inside, his demons raged.

“I wasn’t happy,” he says. “I was sad. I was thinking that the U.S. Army in Vietnam was my family. I put the U.S. Army before my family. I felt like a coward because I quit. I was a warrior and a warrior never quits. Christmas Day, Santa Claus, blah blah blah. I felt paralyzed. I lost my mind.”

Otero-Barreto checked into a hospital, where doctors diagnosed him with combat fatigue – the Vietnam-era term for post-traumatic stress. He spent 15 days in the facility.

“I was hating my neighbors,” he says. “I was hating the U.S. Army. I was hating my family. I was hating myself. I was a warrior hating everybody. I was feeling guilty. My wife told me that if I didn’t quit the Army mindset we were through. I was hating everybody for seven years, and it wasn’t their fault. It was me.”

He managed to finish his bachelor’s degree, but he was still troubled. “No one else could see what I was seeing. Those moments in life will always be with me.”

GIVING BACK At one point, Otero-Barreto took his medals to the downtown market. He asked a vendor for a coffee and offered one of his medals instead of the $1 price. The vendor refused. Believing the medals were worthless, Otero-Barreto threw all of them away. Fortunately, a neighbor collected them from the trash, and eventually Otero-Barreto got them back.

Even without his medals around to remind him of the war, Otero-Barreto remained angry and depressed. Once, while he was away on a trip, his family got rid of his weapons because they were concerned about his anger. “A warrior with no weapons,” he laments.

In time, Otero-Barreto discovered how to control his demons. He looked for ways to channel his leadership impulses into community service and at home. At a school for young boys, he mentored them and taught boxing lessons. He also installed a basketball court and created a program for youths in his community.

“That was my cure,” he says. “Not the pills.”

Otero-Barreto also credits his family for helping him get through postwar struggles.

“Those were moments when I wasn’t thinking of my wife and kids,” he says. “They kept me, more or less, thinking straight. I have 20 grandchildren, 11 great-grandchildren. You come to my house – that’s my platoon. They call me abuelo – grandfather. They keep me in my mind all the time.”

In the community of Vega Baja, Otero-Barreto is highly regarded for assisting veterans. It’s his way of giving back.

“When he joined the post, he became the service officer,” says Angel Narvaez-Negron, a past department commander for Puerto Rico. “Then he became commander, and he is still the commander and service officer. With Jorge, he has the experience. Sometimes I read his positions and he sounds like a lawyer. People come from all the towns around his post just to get service from him. I know that is therapy for him.”

Otero-Barreto has served as post commander for about 10 years. “He uses the same principles for the veterans as the way he runs the post,” Narvaez says. “People love him for that.”

Carlos Ramos, an Army veteran and member of Post 14, is among those who have been helped by Otero-Barreto. After he received a less-than-honorable discharge 12 years ago, Ramos worked a series of minimum-wage jobs, which included stints as assistant manager for a manufacturing company and inventory clerk for a pharmaceutical business.

“I didn’t know about The American Legion until I met Jorge in February 2012,” Ramos says. “I came here with no expectations, and he helped me get my discharge fixed.”

With his upgraded status, Ramos began to receive VA benefits and went back to school. “My studies lifted my spirits a little bit,” he says. “My life has improved since then.” He gives Otero-Barreto credit for turning him around.

Otero-Barreto’s life, too, has improved since he refocused his mind, achieved his degree and began helping veterans. “I feel happy every time they call me or come to me,” he says. “In Puerto Rico, they don’t idolize the veterans. Back in the mainland, it’s ‘Thank you for your service.’ Here, there are no compliments. We don’t work for compliments. We work for our people.

“They are my brothers. We were all in the same military.”

Otero-Barreto is many things to many people: honorable warrior, community leader, veterans advocate. But he says there are other roles he cherishes more.

“I want to be remembered as a good father,” he says. He bows his head and pauses. “A good grandpa. A good father. A good husband. I want them to remember me.”

Henry Howard is deputy director of The American Legion’s Media & Communications Division.

- Magazine