California state veterans homes keep coronavirus at bay as infections devastate long-term care facilities elsewher

Weeks before the nation’s first major COVID-19 outbreak at a private nursing home in Washington state in late February, Dr. Vito Imbasciani and his team at the California Department of Veterans Affairs (CalVet) were preparing for a possible pandemic. The agency made sure it had personal protective equipment for nursing home staff, hand-sanitizing stations for visitor entrances, disposable dinnerware and plans to feed residents in their rooms, isolation areas for those who became infected, and masks for residents to wear when they were not in their rooms.

This advance preparation, spelled out in a detailed 38-point plan, has been a resounding success at a time when nursing homes are often synonymous with rampant coronavirus infections. As of mid-June, only three of the 2,100 residents at California’s eight state veterans homes had contracted COVID-19, and just two had died. And only 19 of the 2,300 staff had tested positive for coronavirus.

CalVet’s success at fending off the novel coronavirus is noteworthy considering that between a third and a half of the COVID-19-related deaths in the United States have occurred in long-term care facilities. State veterans homes in New Jersey, Massachusetts and New York have been especially hard hit. Some private nursing homes are also dealing with large numbers of coronavirus infections and fatalities. But aside from CalVet and a handful of other examples, it’s still not clear if conditions in state veterans homes are substantially different than other long-term care facilities. Among other things, VA does not appear to be fully exercising its oversight with state veterans homes where it pays for residents’ care. And many long-term care facilities are not reporting their case numbers, contributing to a lack of comprehensive data about COVID-19 infections.

In addition, the federal government didn’t start compiling COVID-19 infection and fatality information from individual nursing homes until late May. And while that’s filled some of the information gaps, 20 percent of long-term care facilities didn’t report the required numbers. In addition, many state veterans homes aren’t required to send COVID-19 case counts to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) because they are not Medicare/Medicaid certified.

“I would think the CDC would mandate reporting for the non-certified facilities, whether it’s state veterans homes or privately run nursing homes and all assisted living facilities – but they have not done that,” says Charlene Harrington, professor emerita of nursing and sociology at the University of California San Francisco School of Nursing, who has studied nursing homes for 30 years. “It seems to me to be very important to have transparency so that staff and residents and community members are aware of where the virus is located, since nursing homes are a hot spot for spreading the virus.”

Data aside, nursing home experts and advocates are not surprised that COVID-19 has become a catastrophe for some long-term care facilities. “These homes were not delivering quality care when the virus hit,” Harrington says. “We know that 75 percent of nursing homes in the United States have inadequate staffing that doesn’t meet professional standards. The lack of testing and the lack of personal protective equipment was also a problem.”

All of these would apply even if there had never been a coronavirus pandemic. “There are outbreaks of norovirus, C. diff and staph in nursing homes all the time,” Harrington says. “Every nursing home needs to have supplies and isolation areas and infection control plans. And they didn’t when the virus hit.”

State veterans homes may also not get as much scrutiny, particularly facilities that are not certified by Medicare or Medicaid. VA, which pays state veterans homes a daily fee to care for qualified residents, can inspect their facilities. But the federal agency has been criticized for failing to exercise that authority or share the results. In May, four Democratic U.S. senators asked the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to review VA’s oversight of state veterans homes in light of a 2019 GAO report that recommended the agency improve its efforts.

“The recent deaths of veteran residents and other care challenges at state veterans homes during the COVID-19 public health emergency remind us that VA’s implementation of these recommendations would contribute toward improved care quality at these facilities nationwide and better inform veterans and their families about the best care options,” the letter stated. “While VA does not supervise or control the administration of State Veterans Homes, VA pays for veterans to receive care at these facilities and is the only entity that inspects every SVH in the nation.”

Robyn Grant, of the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, notes that the very nature of nursing homes – congregated living quarters for vulnerable people who require lots of hands-on care – makes them particularly susceptible to a virus such as COVID-19, which is far more contagious than the flu. Infection-control infractions, which have been among the top problems identified during federal nursing home inspections for years – and were the No. 1 issue in 2019 – likely exacerbated the spread of the coronavirus, Grant says. A lack of masks, gloves and disposable gowns has also made it difficult to prevent or contain infections. “There’s no way you can stop the spread of coronavirus if you don’t have proper protective equipment,” she says.

Like Harrington, Grant cites staffing problems as a key contributor to the COVID-19 crisis. Nursing home workers are often poorly paid, rarely have benefits and generally can’t afford to stay home if they are sick, she says. Many have to work at more than one facility to make ends meet and may have transmitted the virus between the nursing homes where they work. “This long-term issue of not paying staff a living wage has come home to roost,” Grant says. “Staff and residents are paying the price.”

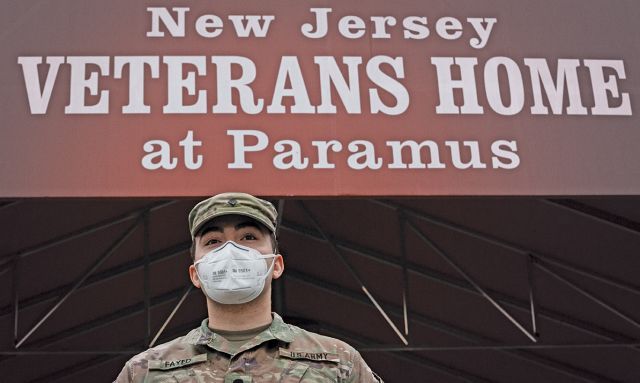

Amid the pandemic, the National Guard has been called in to inspect, sanitize, provide additional medical staff, distribute supplies, expand bed capacity and assist with COVID-19 testing at nursing homes, veterans homes and assisted living facilities in at least 16 states. Combat medics were among the 245 members of the New Jersey National Guard deployed to three state veterans homes. Forty Pennsylvania Guardsmen have provided staffing assistance in one of that state’s veterans homes. The Michigan National Guard has helped its state veterans homes screen employees for symptoms since March 18.

As of mid-June, the National Guard had added more than 18,000 beds to assisted living centers, VA facilities and other care centers, says Maj. Rob Perino, National Guard Bureau spokesman. The Guard had also disinfected 1,900 long-term care facilities, nursing homes, correctional facilities, VA centers, shelters and other public places to prevent the spread of COVID-19. It tested or screened 2.4 million people at drive-through testing sites, veterans homes, hospitals and other settings across the country.

Utilizing the National Guard is a temporary solution, Grant says. Going forward, nursing homes need to pay staff higher wages, provide hazard pay during the pandemic and offer monetary support for things such as child care given that the COVID-19 crisis has closed schools. “Staff are one of the keys,” Grant says.

The private nursing home industry has asked for $10 billion in federal aid to pay for staff, personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing, according to a May 6 letter the American Health Care Association sent to the Department of Health and Human Services. A different effort – the Nursing Home COVID-19 Protection and Prevention Act – would provide aid directly to states and Indian tribes to deal with the coronavirus in nursing homes and other health-care facilities, according to the office of U.S. Rep. Seth Moulton, D-Mass., an Iraq War veteran and co-sponsor of the legislation. The assistance could be used to deal with the pandemic in some state veterans homes, depending upon how the facility is governed.

The legislation, authored by U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Ill., is crucial to preparing for a second wave in nursing homes, Moulton says. “Federal officials should pass our bill so that states have more resources and strike teams that can go in and help. The key ... is testing, tracing, treatment and protective equipment for staff and residents, continuing research that gives us proof that what we think we know about the virus is true,” he adds.

Meanwhile, CalVet’s careful preparation appears to be the antithesis of what transpired at many other nursing homes. And it illuminates another crucial element in preventing a COVID-19-type crisis. “We know that leadership can make an enormous difference in the quality of a nursing home’s care,” Grant says.

That’s abundantly clear in the details of the COVID-19 Preparation and Risk Reduction Action Plan drafted by CalVet director Imbasciani – a 27-year veteran of the Army Medical Corps – and Thomas Bucci, the department’s director of long-term care. Bucci is an Air Force veteran who had decades of health-care administration experience before joining CalVet.

Beyond making sure the state’s eight veterans homes were well-stocked with personal protective equipment – down to fit‑testing staff for N95 masks – they directed each home to review and update its emergency operations plan, educated staff about infection control, increased hand sanitizer supplies, minimized entry points to make it easier to screen visitors, scheduled social distancing training for 1,000 of the most mobile residents, and started screening all staff at the beginning of their shifts. The list goes on to include contingency plans for providing residents their medications in the event of a serious COVID-19 outbreak at any of the agency’s three pharmacies.

Then on March 15, CalVet closed the state veterans homes to all visitors except for families with loved ones in hospice care. In a note to families the day before suspending visitor access, Imbasciani acknowledged the stress the decision would cause and promised nursing home staff would help families stay in contact with residents by assisting with video calls via cellphone or laptop. “I don’t take this decision lightly, but as a physician, I know it is medically necessary,” he wrote of the closure. “I ask for your patience and understanding and hope you know that every step we are taking is to keep you and your loved ones safe.”

This and other proactive decisions meant that six months into the pandemic, just three of 2,100 residents had contracted COVID-19 and only two died. As of mid-June, that closure remained in place. And there are significant challenges ahead. The cost of responding to the coronavirus pandemic – and the sharp economic downturn – has ravaged state budgets. California, Oregon, Washington, Nevada and Colorado joined forces to ask Congress for $1 trillion in COVID-19 relief funds. If the federal government doesn’t come through, California may close one of its state veterans homes and delay spending on other veterans programs to help deal with the state’s projected $53 billion budget deficit.

Even without the fiscal challenges, state veterans homes and private long-term care facilities will be vulnerable to COVID-19 for some time, Harrington says. “Even if and when the infection levels out in the general population, it’s going to continue to be a problem in nursing homes and assisted living facilities – until we get the vaccine.”

Ken Olsen is a frequent contributor to The American Legion Magazine.

- Magazine