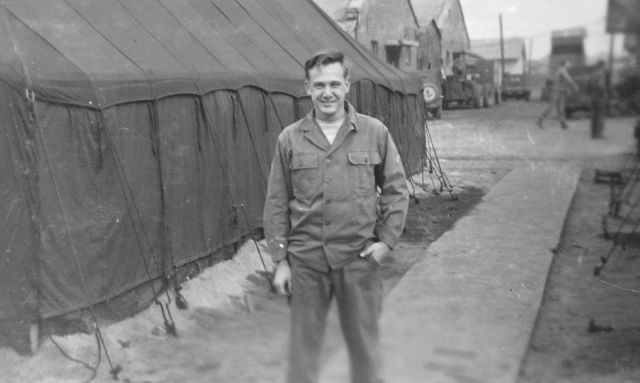

In one of his last interviews, Korean War veteran Charlie Gebhardt recalls the “frozen Chosin.”

Growing up on Chicago’s West Side, Charles “Charlie” Gebhardt thought he knew how brutally cold winter could be. But the Army sergeant changed his mind after fighting in the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir in Korea, where he endured temperatures 35 degrees below zero.

“My feet were like balls of lead,” said Gebhardt, a 21-year member of Boone American Legion Post 77 in Belvidere, Ill. “My fingers were turning black. You can’t imagine how cold it was.”

Freezing weather was only one of the hardships facing Gebhardt in November 1950, during the first year of the war. Months before, North Korean troops invaded South Korea without provocation. In response, a coalition of South Korean and U.N. forces led by the United States retook much of the lost territory and turned the tide in South Korea’s favor. Many thought the “police action” would be over by Christmas, with the two halves of the country reunited under democratic rule.

Everything changed in October, though, when communist China, which borders North Korea, entered the war. On Nov. 27, close to 120,000 Chinese troops encircled and attacked U.S. Marine Corps and Army units near the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea. This was the start of a unrelenting 17-day battle fought in some of the coldest conditions of the war, resulting in nearly 2,500 U.S. troops killed in action, 5,000 wounded and another 8,000 who suffered from frostbite.

“I got up there on Nov. 27, 10 a.m., 3 miles north of the inlet, and we got hit at 8:15 that night by the Chinese,” Gebhardt recalled. “The Chinese had warned us. They didn’t want us messing with those reservoirs.”

Gebhardt, who was attending Officer Candidate School when the Korean War broke out, served as an intelligence and planning specialist with the Army’s 7th Infantry Division, 29th Infantry Regiment (later, 32nd Infantry Regiment). He believed the American forces were caught off guard by the intensity of the Chinese attack and reacted the best they could in a chaotic situation.

“We were thrown in at the last second, 2,389 Army guys and 700 South Korean kids who were grabbed off the street,” Gebhardt said. “We were short two infantry battalions and a brigade of artillery. It was such a helter-skelter operation.”

Surrounded and outnumbered, the American units organized a fighting retreat toward an evacuation seaport, marching 70 miles through treacherous mountains on an unpaved road. This was the only retreat route available to U.S. forces, and the Chinese were waiting for them.

“I kept people moving,” Gebhardt said. “I got guys together to try to break the roadblocks the Chinese set up. There was no communication with the outside world, except for a Marine captain who called in air support.”

Provided by Marine Corps fighter-bombers, that air support proved crucial, inflicting heavy casualties on Chinese troops and giving the retreating soldiers and Marines an opportunity to make it to safety.

Gebhardt had no choice but to take his situation hour by hour and minute by minute.

“I was just trying to survive the moment,” he said. “The Chinese had us surrounded and we were outnumbered 10 to one. We were fighting the impossible. Death was always there. You were always next.”

The rifles’ lubricating oil froze, rendering them useless. Batteries in jeeps, trucks and radios wouldn’t work properly and quickly ran down. Medical supplies, including blood plasma, froze too. Morphine syrettes used for painful wounds had to be defrosted in medics’ mouths before they could be injected. Frostbite caused more casualties among U.S. troops than enemy fire.

For Gebhardt, the cold was punishing, but he survived it. “I had a good winter jacket, and I was told to always have a pair of socks under your armpits,” he said. “That really helped. I had a sweater and heavy socks. But we just had combat jeans (pants) and regular combat boots (instead of winter boots). It was just cold, very cold. It was never warm enough.”

After days of fighting, the Army and Marine units safely made it out. But because of the freezing conditions, many wounded were left behind.

“We walked across the ice and got to the Marines, and a Marine colonel chastised us for leaving our wounded,” Gebhardt said. “I got into a warming tent, recovered from the cold and tried to organize a way to rescue those left behind with some trucks. An officer said, ‘If you get some men who are nuts enough to go with you, I’ll supply the trucks and drivers.’ So, I found 46 nuts who were willing to go back, and we rescued 84 men who were in bad shape. They were wounded or frozen. Their wounds were unattended.”

For that rescue mission, which in all likelihood saved the lives of those 84 men, Gebhardt was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

The battle took its toll on Gebhardt, however. He collapsed from pneumonia and exhaustion and was evacuated by plane Dec. 4 to a rear area, where he eventually recovered.

Asked what he remembers most about the battle, he didn’t hesitate: the high price his unit paid in casualties. “Only 385 out of 2,389 Army GIs escaped the battle without being killed, wounded, surrendered or missing in action,” he said. “Only three officers remained (out of more than 100).”

Gebhardt’s Korean War was far from over. He was wounded in March 1951 when shrapnel from a mortar round pierced his right hand.

“I was outside a command post in South Korea and raised my hand instinctively to protect myself and was wounded,” he said. “No big deal. They put a small bandage on it.” Because he never reported the wound, he never received a Purple Heart.

Gebhardt received a battlefield promotion to second lieutenant, and later to captain. He returned to the United States in July 1951 but was back in Korea a year later, working at air fields K-14 in Kimpo and K-16 in Seoul with the 811th Engineer Aviation Battalion. He left active duty upon coming home in 1953.

Gebhardt returned to the Chicagoland area, where he worked for Indiana Harbor Belt Railroad as a switchman, conductor and yardmaster. He earned a degree and became a leader in the United Transportation Union.

In 1970, Gebhardt married his wife, Linnea, and they had two children, John and Julie. He was active in the Belvidere community and served in an honor guard for veteran burials. “I’ve had a good life,” he said. “The whole thing has been a good life.”

When telling others about the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir, Genhardt’s eyes lit up and his voice grew strong. “The Army was there!” he said. “The Marines weren’t the only ones who were there.”

For the rest of his life, Gebhardt held close his memories of fighting in the “forgotten war.”

“Yes, I had to put up with a lot of combat, but I got through it because I had so many great people beside me,” he said. “I don’t care about the awards and decorations that much. The only badge I really respect is the Combat Infantry Badge. I’d do it all again, because of my band of brothers.”

Robert Randall Ryder is a Marine Corps veteran who served in Operation Desert Storm. He writes about military history for local and national magazines.

Editor’s note: Charles “Charlie” Gebhardt died Dec. 25, 2019, and is buried at Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery in Elmwood, Ill.

- Magazine