‘Our gift to ourselves’

With 424 sites spanning 85 million acres – including parks, historic sites, monuments, battlefields, lakeshores, seashores, riverways, scenic trails and recreation areas – the National Park Service (NPS) has one of America’s highest charges to keep.

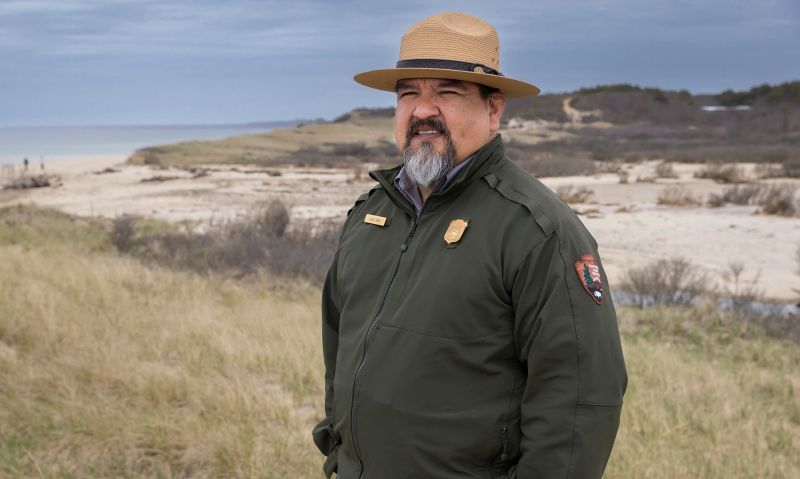

Since 1916, NPS has maintained and managed lands considered to be the nation’s crown jewels – a duty that encompasses not only preservation but, in many places, education and interpretation. For Charles “Chuck” Sams III, the agency’s 19th director and the first Native American to serve in the position, the entire enterprise boils down to one word: stewardship.

Whether that’s rock carvings at Petrified Forest in Arizona or the Tuskegee Airmen hangars in Alabama, the National Park Service’s 20,000 employees are custodians of a continent-spanning story that belongs to all Americans.

“If we are to continue to be America’s best idea, we must be the stewards of those things, not just for ourselves but for seven generations down the road,” Sams says.

A Gulf War Navy veteran, Sams served as an intelligence specialist with Medium Attack Squadron 155, the “Silver Foxes.” Embarked on the carrier USS Ranger, he worked as a mission planner developing strike packages for air crews in the push to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait.

Sams continued his service as a reservist, assigned to Joint Intelligence Command Pacific and Headquarters Defense Intelligence Agency. With degrees in business administration and indigenous people law, he has three decades of experience in the natural resources field, serving in state and tribal government and the nonprofit conservation sector.

He’s also a past commander and adjutant of George Denis Post 140 in Mission, Ore., where he’s still an active member. “I appreciate the Legion’s work with younger veterans,” he says, “especially as they transition to civilian life.”

Sams recently spoke with The American Legion Magazine about his love for America’s national parks, their enduring ties to the military and veterans, his priorities as director and more.

How did your native heritage and background shape your love of the land?

I was born in Portland but raised in Northeast Oregon on the Umatilla Indian Reservation near the town of Pendleton, and I’m Walla Walla and Cayuse. We have a foundational belief system that tells us when we were created as humans we received our eyesight from the eagle, our hearing from the owl, our skin from the elk, and our nervous system and blood-carrying system from the plants. There was a promise, though, that once we were made human beings we would be the stewards of both the flora and fauna, and that was central to my understanding of who I was as an individual and as a member of my tribe.

My grandfather, the late Charles F. Sams Sr., and his brothers all fought during the Second World War, and so I grew up around the ethos that we were a warrior society. Not only did we have the responsibility of stewarding the resources, but we were to protect those resources, and we would do so by joining the military. So when I graduated high school, I took off two weeks later to join the Navy.

You’re part of a long line of military service, then.

My father served during the Vietnam era. He worked in signals as a radioman. My grandfather served as a gunner’s mate in the Second World War, aboard USS Converse. And his brothers, my great-uncles, served in North Africa and the Italian campaign and eventually the invasion of Europe. Those six boys served all over the place, and I grew up with a lot of stories about their experiences, good and bad. But I always marveled at that ideal that it was important you give back to your nation, and that was twofold in my case. We ceded our lands to the United States, and in return the United States was supposed to be our protector. Since 1855, my tribe has fought alongside the United States in all its wars. So I knew from a very young age that I would join the service.

Besides the parks, NPS manages and maintains dozens of battlefields, monuments and historical sites. As a veteran, what does that responsibility mean to you?

I tell the story of being a young sailor finishing A school in Virginia Beach, and we had a two-week period between classes. Four of us went from Maine to Florida visiting as many national parks and monuments as we could. A good number on the East Coast honor our veterans. As someone in their first year of military service, I saw that long line and continuity, and the importance of a volunteer military in particular. We live in a free country, and it comes at a price. The National Park Service interpretive staff who tell you these stories tell it with great passion, but they tell it truthfully and openly without leading you to a conclusion.

When I was at Antietam, we showed up late after spending most of our day at Gettysburg, and a park staff member told us that the gates would close within an hour. He took the time to talk about the 5,000 buried at the national cemetery and then took us to Antietam Creek to talk about the battle itself. Years later, I came to recognize he wasn’t an interpretive ranger. He was actually part of the maintenance staff.

I’ve traveled to over 60 parks in the last year, in 26 states. It doesn’t matter if you’re an interpretive ranger or a natural resource ranger, or part of the maintenance or administrative staff. The staff of the National Park Service know the history of their parks and they’re excited to tell the story.

Sounds like that early road trip made a deep impression on you.

I was a lowly E-3 with no money. (laughs) We couldn’t think of a better way to spend those two weeks than to go to the national parks and camp along the way. A white kid from New Jersey, an African American kid from the Chicago area, a Hispanic kid from Texas, and me, a Native American kid from Oregon – we all had different experiences based on our ethnicities and backgrounds, but it was great to talk about it. We talked about slavery, the Spanish American War, civil rights and rioting, all these things. Parks offer you that immersion into the American experience I don’t think you can find anywhere else. I felt it more alive than I did learning it in high school, even taking history classes in college, because it was living history.

America’s parks and the military have strong ties, going back to cavalry troops serving as some of the first park rangers. How does that special relationship continue today?

Prior to the establishment of the National Park Service, yes, the Army was predominately responsible for protecting our national parks, whether that was at Yellowstone or Yosemite. Many of those soldiers and cavalrymen ended up doing interpretation of those parks. Come 1916, with the passing of the Organic Act, the National Park Service ended up adopting a lot of retired soldiers into the system. Many of our first park superintendents were retired lieutenant colonels and colonels. Not only did we have these large, iconic national parks in our system, but a number of military memorials and monuments were put in our charge.

Twenty-four percent of my work force is veterans, and we still wear the green and gray – uniforms that pretty much match what the military was wearing in 1916. So we have that very strong connection. Each of our superintendents, he or she, are captains of their own ship, but they follow the structure under which we provide resources and guidance from regional offices and the headquarters in Washington, D.C. We have a lot of elements from our relationship with the Army that still play out today as a civilian organization, and as you can see from the staff, they have the discipline of being able to do a lot with very little at times.

What are you doing to increase the number of veterans working or volunteering for NPS?

We have a number of national battlefields up and down the East Coast, and American Indian battlefields out west, and so we’re able to attract a lot of veterans who have a strong sense of service but also have a strong interest in history. And many of our volunteers who worked as mechanics and other trades within the service bring their talents to the National Park Service.

We have a direct-hire program in partnership with the Department of Defense where we’re working with a number of craftspeople, to take them through our program so they can transition with their federal years of the military. Whether that’s after four years or 20, they can come into the National Park Service, and we’re able to harness their skills to continue to serve in a different way and in a different uniform.

You’ve said you want to boost park service staff and address a massive maintenance backlog. Where is NPS on these priorities?

Our backlog on deferred maintenance repairs is second only to DoD, and we’re second only to DoD in the number of assets we own ... nearly $300 billion worth. The last big influx of funding came between 1956 and 1966, called Mission 66, in celebration of the 50th year of the National Park Service. Advance 60 years, the Great American Outdoors Act comes, and is now the single largest investment that we’re seeing.

Our staff do a wonderful job of maintaining facilities, but it’s not been easy. When we first looked at it, we weren’t calculating our deferred maintenance up to industry standards, and so it was believed it was only at about $11 billion. Once we were able to do a physical examination, that number doubled. The investments we’re making through the Great American Outdoors Act are tackling those large issues – whether that’s a water treatment plant, septic system, roadway or bridge – so we can keep these places open for the enjoyment of the American people.

We are down 19% in staff from 2011, yet we’ve seen a 20% increase of people coming into the park system. We also have 30 more parks. So we have more resources, more land, more assets to protect and preserve and enhance for Americans’ enjoyment. Yet we were down by 19%. The Inflation Reduction Act helps close that gap. It provides us 5,000 FTEs dedicated to staff and boots on the ground in the parks, not in regional offices and not at headquarters.

Other issues include park access and crowding, especially post-COVID. What’s happening there?

The first time you see the quote “America is loving its parks to death” is in public testimony in 1978, by the National Park Service itself. Here we are, 45 years later, and crowding is taking a toll on our ability to manage access in and out of the parks. Fortunately, we have some of the best social scientists within NPS, and we have a number of tools at our disposal to figure out how we can manage that access, including being able to use GIS (Geographic Information Systems) and other technical types of services to model what that looks like. What might work at Acadia might not work at Zion, and we try to tailor those accesses based on where the park is, what the local community needs, and the current road and infrastructure system.

While I don’t like restrictions through timed entry personally, what we’re seeing from the information we’ve gotten back, especially in the past year, is that people are finding that it works better for them. They can find a place to park, they can enjoy the park a little better, and we’re seeing positive attitudes from the surrounding communities. We’re trying to work hand in hand with the general public, and with our own staff, in figuring out the access issue.

You’ve talked about tribal co-management as a path to helping restore the state of some public lands. Describe those efforts.

My best example is the wildland fires out west. What we now know and better understand is that while every tribal member before contact may not have been agriculturalists, they were at least horticulturalists. What everybody else has called wild we’ve always called home, and for thousands of years we maintained the forest beds. We ensured those areas received natural and manmade fire so there were healthy grasslands and meadows, a healthy undercarriage under the forest that didn’t build itself up. But for the last 80+ years we’ve consistently said all fire is bad, and the moment a fire strike happens – either by lightning or manmade – we instantly put it out. These fuels built up, and we’re seeing the results of that.

The National Park Service is working more cooperatively with tribes across the United States, particularly in the West, doing prescribed burns. At Great Smoky, the superintendent has been working closely with the Cherokee Nation, their fire crews and our fire crews together, to start burning some of that undercarriage so that we’re not seeing what we’ve seen out west.

Through co-management and co-stewardship, we have an opportunity to work with tribes that have been doing this for thousands of years, learn the lessons from them and start applying them within the Park Service.

What other challenges are you taking on?

Two issues surprised me coming into this position. One was housing. (The Airbnb model) has really blossomed over the last decade, but it’s taken a lot of lease and rental properties off the market that our staff used to have available to them as they came in as seasonal workers or moved site to site. We need to improve the housing we have within the park system – modernize it and, in some cases, demolish and rebuild. We’ve done that at Yosemite, at Yellowstone and at Grand Teton, but we’re also using the funds to lease housing.

If you don’t have a roof over your head it’s hard to do your job, and if you can’t afford that roof over your head, it’s that much harder. This fiscal year (FY24), I’ve asked for $15 million to tackle it, and we have another $100 million in projects and line items that are going toward housing over the next two years.

The other issue, which was a little more disappointing, was the amount of low morale within the park service. There had been a lot of bullying, sexual harassment, lack of accountability and discipline, and we’ve hit that head on. We want to ensure that people have a safe work environment, that they’re respected for what they do. We want an engaged workforce that understands everything from the bottom up, and from the top down, and the only way that works is if you have clear communication. I learned that from the Navy.

What message do you want to give Americans about the park system?

I want the American people to know that the parks are theirs. This is our gift to ourselves as Americans, and they should get out there and see their parks and to engage not just in recreation and with the flora and fauna, but to engage with the deep and rich history that is us as America.

Matt Grills is managing editor of The American Legion Magazine.