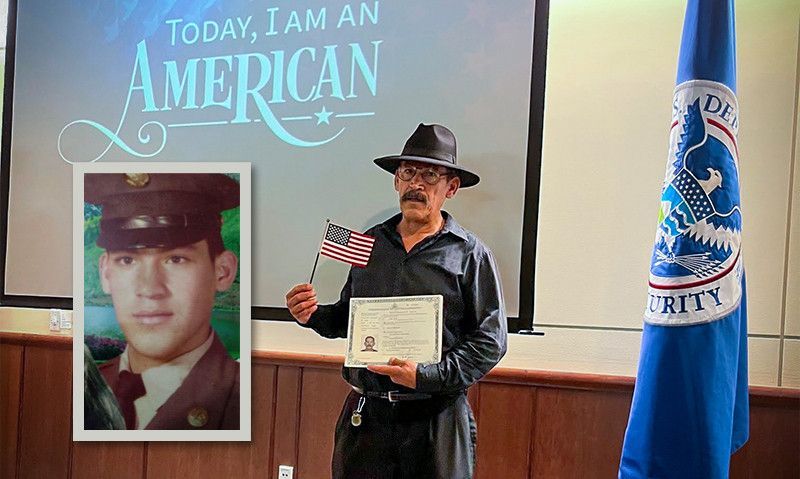

“I’ve been waiting for this day as long as I can remember,” Army veteran Jose Tinajero says.

Jose Tinajero had long since given up returning to the United States when he met Tran Dang at a legal aid workshop for deported veterans in Guadalajara, Mexico, in 2021. He hadn’t so much as consulted an attorney since an immigration judge deported him for life 25 years earlier. This after he pled guilty to a state drug charge on the advice of a public defender who assured him his military service would prevent him from being kicked out of the United States.

“I was broken-hearted and beaten,” says Tinajero, who served in the Army from 1976 to 1979. He was also frightened because of the stories he’d heard about Mexico, where he hadn’t lived since he was a child. Yet he felt he had no option but to try to rebuild his life in this unfamiliar place.

His exile is finally over. Last spring, with Dang’s help and financial support from American Legion Post 7 in Lake Chapala, Mexico, Tinajero was able to return to Washington state to clear his name and claim the citizenship he was due decades earlier because of his military service. Today, he is living and working in the Seattle area and plans to earn his master’s degree in computing. “I should have never left,” he says. “I feel like the laws that lead to the deportation of veterans should be amended or repealed.”

The American Legion shares some of Tinajero’s concerns. “Men and women who serve honorably should not face undue barriers to citizenship or face deportation from the country they served or fought to defend,” The American Legion National Commander Dan Seehafer said in a September letter to Congress in support of the Veteran Service Recognition Act of 2023, “Congress must act to ensure our nation honors the service of non-citizen immigrants who have honorably served our nation.”

That’s particularly important as the U.S. military struggles to find enough new recruits, Dang notes.

Migrant to military Tinajero came to the United States from Reynosa, Mexico, with his parents and sister in 1969. They became legal permanent residents and migrant farm workers, following the summer harvest from the Pacific Northwest to the upper Midwest. “You name it, I picked it,” Tinajero says. Winters, his parents worked in Texas’ citrus groves while he and his sister attended school in McAllen, Texas, where they recited the Pledge of Allegiance each morning. “I was part of this country,” Tinajero says.

He joined the Army right after high school, eager to escape McAllen and the tumult of his parents’ breakup.

“I considered myself an American,” Tinajero says. “I wanted to serve my country.” The recruiter told him he’d automatically become a citizen when he joined the Army. “I didn’t have any reason not to believe him,” Tinajero says. Like thousands of other immigrant servicemembers, he was eligible for citizenship because of his military service. But he didn’t realize there was a formal application process – and no one mentioned that requirement to him while he was in the Army.

After four years of active duty and an honorable discharge, Tinajero joined his father planting trees for a variety of timber companies in the southern United States. He eventually landed in Seattle, where he says he fell in with the wrong crowd. Tinajero appeared in court on state drug charges in 1994. His public defender encouraged him to take a plea deal and assured him that his military service would spare him from being deported, he says. Tinajero earned a substantial reduction in his 48-month prison sentence with good behavior. But the moment he was released in 1996, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents took him to a detention facility in Seattle where he was held for another year.

When he appeared before an immigration judge in April 1997, Tinajero expected to have the opportunity to make his case for remining in the United States. However, because he wasn’t a citizen, his drug offense was grounds for automatic deportation under the harsh federal immigration laws passed in the 1990s. So the judge instead expelled him for life.

Remain in Mexico Broken, afraid and cut off from his family in the United States, Tinajero worked in the hotel industry and then as a mechanic. He eventually landed a job in a call center and earned his bachelor’s degree in computer science engineering. In 2021, Tinajero met Dang, an attorney and founder of the Rhizome Center for Migrants, which provides legal assistance to people who have been deported to Mexico. She had contacted American Legion Post 7 in an effort to locate and offer assistance to deported veterans who might be allowed to return to the United States under President Biden’s Immigrant Military Members and Veterans Initiative. Post 7 covered food and travel costs that enabled deported veterans from six Mexican states to attend The Rhizome Center’s Veterans Benefits and Citizenship Workshop in Guadalajara in August 2021.

Post Commander Randall Butler says it was an easy decision for him and his board. “We’re here to help veterans,” he says of Post 7, the largest south of the border.

Dang filed a citizenship application on Tinajero’s behalf in October 2022, raising the possibility he would be able to see some of his U.S. family again.. But his sister, an Army veteran who lived in North Carolina, died before he was allowed to temporarily return to the United States under what’s known as humanitarian parole. And 19 days before Tinajero was to meet with U.S. Immigration and complete his citizenship application, a 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruling made Tinajero ineligible for citizenship based on his military service because of his decades-old state drug conviction.

It’s the sort of misfortune that followed Tinajero for years, Dang says. If the Army had helped him navigate the citizenship application process during basic training in 1976, he wouldn’t have been deported. If Veterans Treatment Court had been available when he was arrested, Tinajero would have had the option of diversion and drug counseling instead of conviction and deportation. If the federal legislation that made Tinajero’s drug conviction grounds for automatic deportation hadn’t become law the day he first appeared before the Immigration Court in 1996, he might have been able to stay in the United States. And if he had been able to complete his 2023 citizenship interview three weeks earlier, the appeals court decision wouldn’t have disqualified him, Dang says.

As a result, Tinajero had only one option: clear his criminal record. A pro bono attorney from the law firm of Foster Garvey and the Seattle Clemency Project successfully petitioned a Superior Court judge to dismiss the 1994 conviction based on ineffective assistance of counsel. Tinajero renewed his citizenship application and took the oath July 26. “It means the world to me,” Tinajero says. “I’ve been waiting for this day as long as I can remember.”

He credits Dang for turning his life around and American Legion Post 7 for helping make his journey home a reality. “I have nothing but praise for the organization and you guys for being solid with me when I needed it,” Tinajero says.

Tinajero is one of 84 veterans to return to the United States under Biden’s initiative and one of four deported veterans Dang is helping navigate a possible return to the United States, she says.

For Butler, being a part of the effort to help Tinajero and other deported veterans is a way of fulfilling a promise. “My slogan,” he says, “is don’t leave a veteran behind.”

Ken Olsen is a frequent contributor to The American Legion Magazine.

- Security