Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.: “We’ll start the war from right here!”

Theodore Roosevelt Jr., who had been shot in the leg and gassed nearly to blindness in World War I, was not going to let World War II go by without his direct involvement. First wave. D-Day. He was 56 and walked with a cane when his Higgins Boat reached Utah Beach on June 6, 1944.

Eldest son of the 26th U.S. president, Roosevelt Jr. famously said The American Legion could never have been founded by one individual. It was a point he made often in 1919, the organization’s founding year, when crowds of newly minted veterans shouted for him to serve as the first national commander. He declined the nomination in order to ensure that The American Legion would not be perceived as politically partisan in any way.

Prior to U.S. entry in World War I, he helped form American Legion, Inc., a national network of citizens trained to serve should the call to arms come. He led combat missions across France and soon after the armistice of Nov. 11, 1918, arranged the earliest meetings to plan what would become The American Legion. In May 1919, he presided over the St. Louis Caucus where the Preamble to the American Legion Constitution was drafted and most of the organization’s purposes and values were set in motion.

Like many of The American Legion’s earliest founders, Roosevelt Jr. returned to duty during World War II. He was a beloved leader, considered a “dog-faced general” by his troops, and, as he had done during World War I, he gained the respect of top career generals.

One of those generals, however, was opposed to Roosevelt Jr.’s request to enter the European Theater at Normandy as part of history’s largest amphibious military invasion. Maj. Gen. Raymond “Tubby” Barton rejected Brig. Gen. Roosevelt Jr.’s verbal requests. Then, he put it in writing, stating that his experience and ability to report the situation from the beach back to the command would be vital to the operation’s success. He also noted that, “I personally know both officers and men of these advance units and believe that it will steady them to know that I am with them.” Reluctantly, Barton finally gave in.

Roosevelt Jr. became the only U.S. general to storm the beaches in the first wave of the Normandy invasion, leading the 4th Infantry Division, 8th Infantry Regiment, into France. His landing craft famously drifted off course and reached shore approximately one mile from its target destination on Utah Beach. Reportedly, he let the troops know he didn’t care where they landed. “We’ll start the war from right here!” he is said to have shouted to the young soldiers scrambling onto the beachhead.

As German forces began firing, Roosevelt Jr., also reportedly befuddled the enemy by limping back and forth to the Higgins Boat, armed only with a pistol, to keep the troops moving.

That same morning, Roosevelt Jr.’s son, Capt. Quentin Roosevelt II, stormed Omaha Beach. Roosevelt Jr. was the oldest man in the invasion and the only father whose son also came ashore on D-Day.

“His valor, courage, and presence in the very front of the attack and his complete unconcern at being under heavy fire inspired the troops to heights of enthusiasm and self-sacrifice,” his Medal of Honor citation would later read. “Although the enemy had the beach under constant direct fire, Brig. Gen. Roosevelt moved from one locality to another, rallying men around him, directed and personally led them against the enemy. Under his seasoned, precise, calm, and unfaltering leadership, assault troops reduced beach strong points and rapidly moved inland with minimum casualties. He thus contributed substantially to the successful establishment of the beachhead in France.”

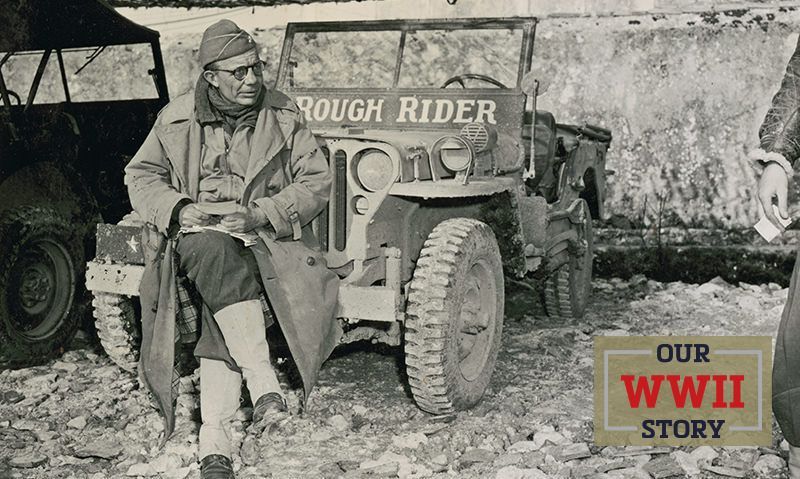

Once inland, he was often found among the rank-and-file soldiers, seated in his jeep, which bore the name “Rough Riders” in honor of the 1st Cavalry Brigade his father had led in battle during the Spanish American War.

Five weeks after coming ashore at Utah Beach, Theodore Roosevelt Jr., died of a heart attack and was buried in Ste. Mere-Eglise. His grave was later moved to the Normandy American Cemetery near Omaha Beach, where it is often visited by current-day American Legion national commanders.

The American Legion provides media tools; a chronology of the organization’s role before, during and after World War II; video links; graphic elements and more to help local posts honor the 75th anniversary of the war’s end. Click here to download the media kit.

Participating Legion posts are also welcome to submit their stories in the “My WWII Story” section of legion.org/legiontown. They are also encouraged to add to their post histories on the national Legacy & Vision website at legion.org/centennial. Both platforms offer easy sharing for social media. Selected submissions will be edited for publication in the September 2020 American Legion Magazine.